Can AI Be Criminally Liable?

Newsletter Issue 30: As AI systems make critical decisions, the stakes are rising, and in some cases, the people behind them are facing criminal charges.

Around the world, prosecutors are circling, and in some cases, people are already being charged for what their AI systems did. World legal systems are catching up with reckless automation, and the consequences are real: injury, death, and yes, prison time. In this article, we explore how criminal liability is entering the AI age, what cases are already unfolding, and why developers, founders, and product teams need to pay attention right now.

On a late evening in 2018, a self-driving Uber test vehicle in Tempe, Arizona struck and killed a pedestrian. It was the first recorded case of an autonomous car killing a person.1

The aftermath raised a chilling question for the tech world: who bears the blame when AI-driven systems cause real-world harm?

In this case, prosecutors decided not to charge Uber but instead filed criminal charges against the human safety driver for negligent homicide. This incident, and others like it, have catalyzed a broader discussion about how far the law will go in holding people (or companies) criminally accountable for the actions of artificial intelligence.

For years, AI-related mishaps were largely met with civil lawsuits or regulatory fines, costly, but not the stuff of prison sentences.

Now that AI systems become ever more entwined with critical decisions affecting life, safety, and fundamental rights, lawmakers are realizing that “we’re not just talking about fines anymore.”

In certain scenarios, AI misuse or failures might land developers, executives, or users in actual criminal court.2

Reckless automation, the deployment of AI without proper care for its risks, could be treated not merely as a business mistake but as a crime.

Our comprehensive article explores the emerging legal frameworks that could criminalize irresponsible AI deployment, moving beyond private civil liability into the public realm of criminal law.

The article will also cover public safety cases (like driverless car accidents), data and privacy violations, and consumer protection issues in holistic way. You will find real-world case studies, from enforcement actions to precedent-setting court decisions, and even commentary on how the law is developing rapidly.

From Civil to Criminal: A New Frontier in AI Accountability

Traditionally, AI-related harms have been addressed through civil liability, lawsuits for negligence or product defects, regulatory penalties, and so on.3 If an AI-powered tool caused financial loss or even personal injury, the usual outcome might be a lawsuit where the company pays damages, or a regulatory fine for breaking rules.

Criminal cases (which can lead to convictions, fines paid to the state, or even imprisonment) were seldom part of the picture in technology failures. After all, we don’t throw engineers in jail when software crashes or a gadget malfunctions under ordinary circumstances.

However, the line between civil and criminal liability is not fixed in stone. It often comes down to severity and culpability. Civil liability is about compensating harm; it’s typically triggered by negligence (a lack of reasonable care) or strict liability (in product defect cases). Criminal liability, on the other hand, is reserved for wrongdoing that society judges to be so bad that it warrants punishment by the state; things like recklessness, wilful misconduct, or intent to do harm.4

In the context of AI, the “new frontier” is where mistakes or misuses of AI are so egregious that they attract criminal scrutiny.

At what point does an AI-related failure stop being a mere accident and start being a crime?

When might an AI developer’s disregard of safety be seen as criminal negligence or recklessness?

When could an AI-driven decision process be involved in something like manslaughter, fraud, or unlawful surveillance charges?

These questions were once largely academic, but they are becoming very real as AI moves into high-stakes domains.

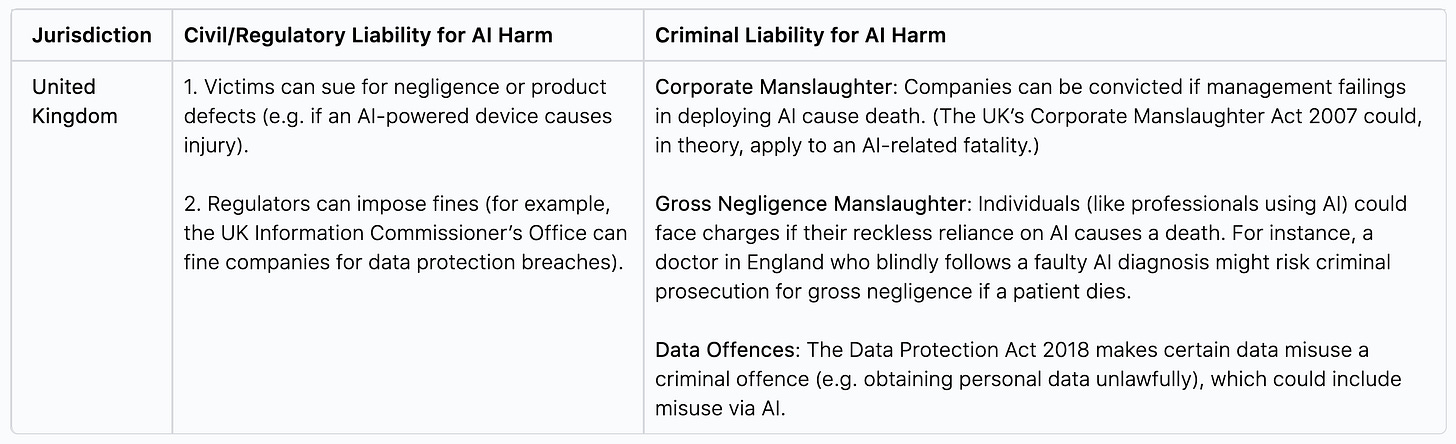

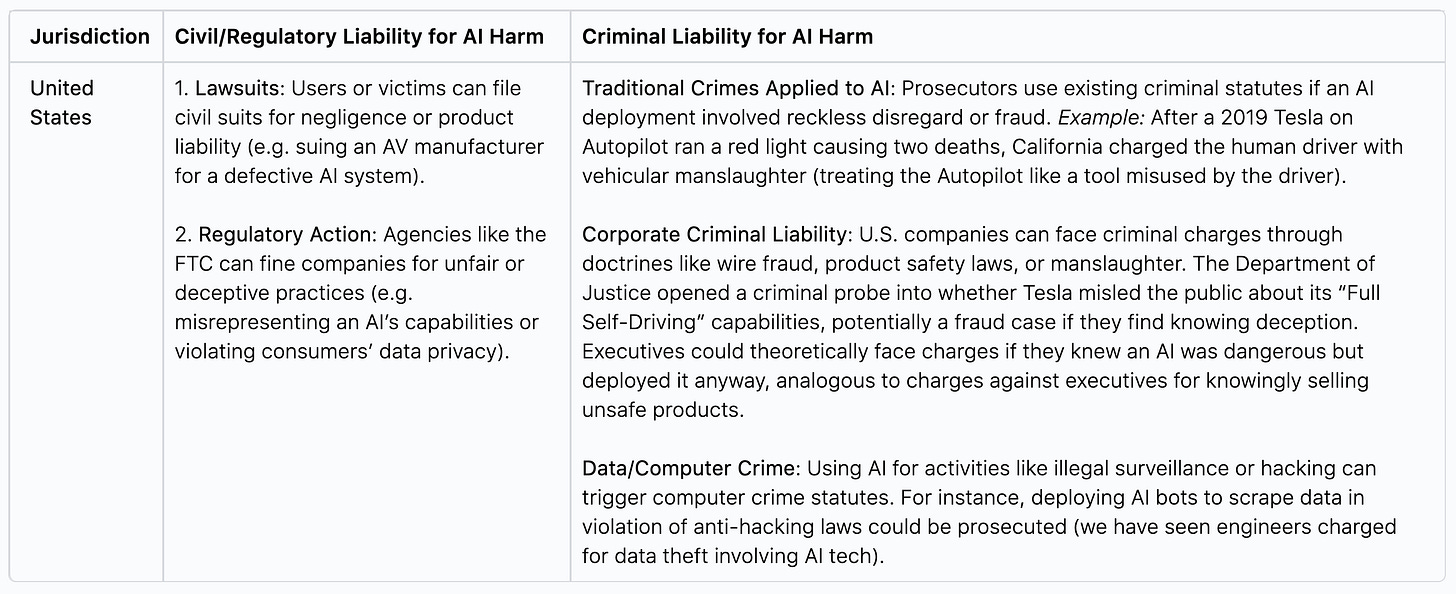

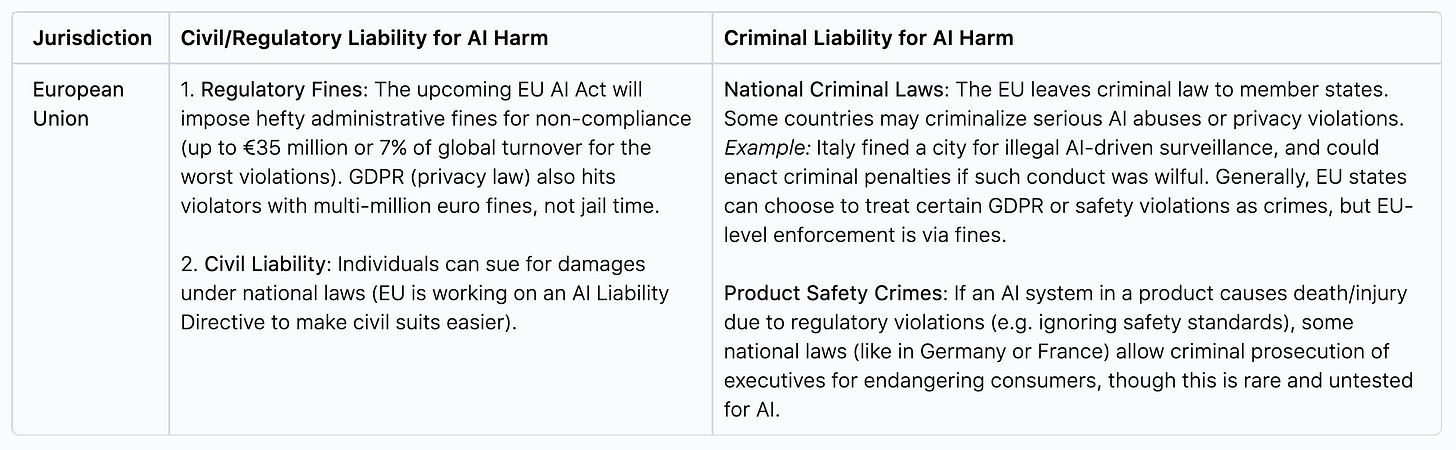

Let us try to clarify the difference with a quick comparison of civil vs criminal liability in the AI context, and how this can vary by jurisdiction:

As the tables above shows, civil liability remains the primary mode for addressing AI harms in most places, but the door to criminal liability is opening, especially for severe cases.

Notably, the UK framework explicitly anticipates criminal charges like corporate or gross negligence manslaughter for conduct causing death, and U.S. authorities are creatively using fraud and negligence laws to tackle AI-related wrongs.5 In the EU, enforcement is so far mostly via fines, but even there, local prosecutors aren’t entirely out of the picture when rules are flouted egregiously.

Why Consider Criminal Liability for AI at All?

You might wonder, why bring criminal law into this at all? Isn’t taking a product off the market and suing for damages enough? The need to criminalize certain AI-related harms comes from the realization that some risks posed by AI are extraordinarily high, a faulty algorithm in an autonomous car or an AI-driven medical device can literally be life or death.

If companies or individuals deploy AI in a reckless way that endangers lives or fundamental rights, lawmakers argue that fines or damage awards may not be a sufficient deterrent or expression of society’s disapproval. Criminal law carries moral weight; it brands the conduct as blameworthy on a societal level (not just “you pay for the damages” but “you committed a wrong against society”).6

If a factory owner wilfully ignores safety warnings and an explosion kills workers, many countries allow criminal charges (like manslaughter) against the owner or managers, not just civil suits.

As AI assumes roles akin to dangerous equipment or critical decision-makers, a similar logic is emerging.

Reckless automation, let’s say, rushing an AI system to market despite known flaws, or ignoring obvious signs of danger, might be viewed like any other grossly negligent conduct. Gross negligence that causes death or serious harm has always been within the radar of criminal law (often termed involuntary manslaughter or criminally negligent homicide).

In short, as AI’s consequences become less hypothetical and more tangible, society is reassessing the balance: we still want innovation, but we also want accountability when things go horribly wrong.

In the next sections of this article, we will address specific areas where this tension is playing out: public safety, data protection, and consumer protection.

When AI Can Kill (or Injure)

Nothing captures the stakes of AI better than scenarios where AI systems can physically harm people. Public safety is paramount, and when AI errors put lives at risk, authorities have shown they are willing to step in with severe consequences. Let’s look at a few key examples and how the law responded:

Autonomous Vehicles and Traffic Accidents

Self-driving cars are a marvel of AI engineering, but what happens when they make a deadly mistake? We have already seen it. The 2018 Uber incident in Arizona, mentioned earlier, is a locus classicus case. Here, the car’s AI failed to properly recognize a pedestrian (49-year-old Elaine Herzberg) crossing the road at night. The backup human driver was allegedly streaming a TV show on her phone instead of paying attention.

The tragic result was a fatal collision. Prosecutors faced a novel situation: an autonomous system was at the helm of the vehicle. They ultimately charged the safety driver, Rafaela Vasquez, with negligent homicide, essentially for recklessly relying on the AI and not intervening.

Uber, the company, was not criminally charged, with officials saying there was “no basis for criminal liability” for the corporation. Ms. Vasquez later pleaded guilty to a lesser charge (endangerment) and received probation.

This Uber case illustrates a key point: under current law, the human in the loop was held accountable, not the AI or its creators. But it raised debate: some argued that Uber’s deployment of a self-driving test vehicle with known software deficiencies (the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) revealed the Uber had disabled the car’s automatic emergency braking to reduce jerky rides) was itself reckless.

If true, should corporate leaders or engineers face consequences?

At least in that case, the answer was no criminal charges for the company, but future cases might differ, especially if evidence shows a company willfully ignored safety. Consider if an autonomous vehicle company knowingly supplies software that they suspect can fail in common situations: if a death results, prosecutors might explore corporate manslaughter charges in a jurisdiction like the UK, or criminal negligence charges in the US.

Indeed, legal scholars have noted that autonomous vehicle accidents highlight how hard it is to pin down “who is responsible”: the driver, the developer, the car manufacturer?7

Uncertainty in liability rules remains, but as one commentator put it: our system is completely unprepared for AI, when it comes to assigning blame.8 The law is now trying to catch up.

Criminal Investigations into Autopilot and Marketing Hype

Tesla’s Autopilot feature has been involved in multiple crashes, including fatalities, when drivers allegedly over-relied on it. U.S. authorities have not shied away from using criminal law tools in this arena. In late 2022, Reuters revealed that the Department of Justice opened a criminal probe into Tesla’s self-driving claims, investigating whether Tesla (and by extension its leadership) misled consumers and investors about the capability of its Autopilot/Full Self-Driving systems.

The probe was reportedly spurred by over a dozen crashes (some fatal) involving Autopilot. If DOJ concludes that Tesla or its executives knowingly exaggerated the safety or autonomy of their cars, they could theoretically be charged with fraud or false advertising, criminal offences.

Therefore, rather than treating autopilot crashes purely as product liability matters or traffic accidents, regulators are asking if there was recklessness or deception from the company side.

What about situations where an AI-related death occurs but no human user is obviously at fault (for instance, if a fully driverless car with no safety driver malfunctioned)?

We have not had that precise scenario yet in public roads, but the law may adopt concepts from existing legal doctrines. In the UK, for example, if a death is caused by a company’s grossly negligent management, the Corporate Manslaughter and Corporate Homicide Act 2007 could make the company criminally liable. It has not been tested with AI, but one can imagine a prosecutor arguing that a company’s organization failed to account for an AI’s risks, leading to a death, analogous to a company failing to enforce safety protocols on a dangerous machine.

Meanwhile, individuals such as engineers or executives could face gross negligence manslaughter charges if their personal actions (or inactions) meet the criteria (duty of care, gross breach causing death).

Legal analysis in England has started to map out how this could apply.9 For instance, scholars have run hypothetical scenarios of a patient dying because a clinician relied on a flawed AI recommendation, could the clinician be done for manslaughter?10 Possibly yes, if their reliance was deemed grossly negligent.

AI in Healthcare: Malpractice or Manslaughter?

AI is being deployed in healthcare for diagnosis, treatment recommendations, and even surgery assistance. If an AI system’s error leads to a patient’s death, we might see criminal inquiries alongside malpractice suits. A provocative term “AI-induced medical manslaughter” has even been discussed in medical law circles.11

The core issue is this: doctors are still responsible for validating AI recommendations, but AI can introduce new traps, automation bias (over-trusting the AI), unexplainable outputs, and conflicts when a doctor’s judgement disagrees with an AI’s suggestion.

If a doctor blindly follows an AI’s wrong diagnosis leading to fatal consequences, is that simple negligence or something criminal?

Traditionally, gross negligence (a truly egregious deviation from standard of care) causing death can be criminal in many jurisdictions. The issue with AI is that doctors might be put in tough spots by systems that are essentially “black boxes.” Current gross negligence standards might unjustly expose conscientious doctors to criminal blame because AI’s complexity adds a new kind of moral luck. The doctor might not even know the AI’s error was possible.12 Shifting to a subjective recklessness standard is ideal in such cases: therefore, that means only punishing the clinician if they knowingly took an unreasonable risk (for example, they knew the AI could be wrong in a dangerous way but used it carelessly).

This is a developing debate, but it highlights that the legal system is actively thinking about how to handle AI-related deaths in healthcare. In any event, a hospital or AI manufacturer that knowingly deploys a medical AI without sufficient validation could even face criminal negligence claims. In the UK, besides targeting individuals, prosecutors could eye the hospital organization under corporate manslaughter if systemic failings (like lack of oversight or training with the AI) contributed to a patient’s death.13

Robots and Industrial Accidents

It is not just software algorithms; physical robots powered by AI have long worked alongside humans in factories, and sometimes caused tragic accidents. Back in 1981, a factory robot in Japan killed a worker (the robot’s arm crushed him), and similar robot-caused fatalities have occurred since. Traditionally, these incidents are handled under workplace safety laws.

Regulatory agencies might fine the company for safety lapses, and in some cases in Western jurisdictions, if an employer was recklessly indifferent to worker safety, criminal charges can be brought.

For example, in the U.S., a wilful violation of safety standards causing a death is a federal crime (a misdemeanor under OSHA law), and in the UK, as noted, corporate or even individual manslaughter charges could be in play. The key is demonstrating recklessness or wilful neglect.

If a robot killed someone because an engineer disabled a safety sensor to speed up production (knowing it was dangerous), that engineer or their supervisors could be singled out by prosecutors. So far, these are rare; most industrial robot deaths have been seen as horrible accidents or civil matters, but as robots get more autonomous, the assignment of blame may sharpen.

In all these public safety contexts, one theme emerges: if humans turn over critical control to AI, the law will still look for a human (or corporate) culprit when things go wrong. Initially, that is often the operator (like the safety driver in the Uber case or the Tesla driver). But we are increasingly seeing questions raised about the developers and companies behind the AI.

Did they recklessly design or deploy the technology?

Did they ignore known risks?

Those questions could form the basis of criminal negligence or recklessness allegations.

A sobering example to consider: imagine an autonomous public transit train run by AI software that had a known glitch in certain weather, but the company failed to fix it or inform anyone. If the train crashes and people die because of that glitch, it is easy to foresee an outcry demanding prison for whoever made that call, and laws are on the books that could support such charges (e.g. involuntary manslaughter for the decision-makers, or even negligent homicide charges for the company if state law permits corporate criminal liability).14

Before this section turns too dark, it is worth noting that the goal of such criminal liability threats is deterrence and accountability, not to punish honest mistakes or stifle innovation. Regulators don’t want to throw a developer in prison because an unpredictable bug caused harm despite everyone’s best efforts. Rather, they want to ensure AI is developed and deployed responsibly, with proper safety nets.

As one DOJ official recently put it, AI is a “a double-edged sword” that may be “the sharpest blade yet,” capable of great good and great harm. For the harms, she noted that misuse of AI could even become an aggravating factor in prosecutions, meaning crimes involving AI abuse might get treated more harshly. That is a hopeful sign that authorities see reckless or malicious use of AI as especially blameworthy. We will explore malicious misuse later; for now, let’s turn to another sphere where AI can do damage: the realm of data and privacy.

AI Crime at the Privacy-Data Precipice

Modern AI is hungry for data, including personal data. From facial recognition cameras scanning public streets to machine learning models crunching our online behaviours, AI often treads uncomfortably close to the line of privacy rights.

Data protection laws (like Europe’s GDPR or California’s privacy regulations) historically enforce compliance through fines and injunctions. But could serious privacy violations involving AI ever be criminal?

In some cases, yes, especially where misuse of data is knowing or particularly egregious. Let’s consider a few situations:

Illegal Surveillance and Facial Recognition

Consider a city government or police department deploying an AI-powered surveillance system that monitors people in public spaces with facial recognition. Suppose this is done without proper legal authority or safeguards, effectively turning the city into a Big Brother panopticon.

In 2024, the city of Trento in Italy faced backlash for exactly this; they used AI for street surveillance and failed to comply with privacy protections, like anonymizing data, in violation of GDPR. The city was fined for this misuse of AI. Now, a fine to a city is one thing, but what about personal liability? Under some national laws, officials could potentially face criminal charges if they wilfully violated privacy laws.

For instance, certain countries treat the unlawful surveillance of individuals as a criminal offence, especially when done by government actors. Even if not, consider that if a private company did the same thing (set up an AI surveillance network without consent), they could be prosecuted under laws against unauthorized data processing or unlawful interception. The UK’s Data Protection Act, for example, contains criminal provisions that can be used against people who knowingly misuse personal data (like obtaining or disclosing personal data without consent), one could imagine an employee or contractor being charged if they, say, used face-recognition AI on customers or citizens illegally.

Also, some jurisdictions have specific laws against certain types of surveillance. In the U.S., recording someone’s communications without consent can trigger federal or state wiretapping statutes (which carry criminal penalties). If an AI tool eavesdrops on conversations (e.g., AI agents recording without permission due to a “glitch” or, worse, a feature), companies could face severe repercussions.

So far, we have mostly seen big civil class actions for things like that (Amazon and Google have been sued for their voice assistants allegedly recording children or others without consent), but a sufficiently outrageous case could spark a state Attorney General or federal prosecutor to pursue charges.

Data Breaches and Negligence

AI can inadvertently cause data breaches, for example, an AI developer might leave a dataset of personal information unsecured on a server, or an AI model might leak private info because it wasn’t properly sanitized (there have been instances of AI models regurgitating sensitive training data). Most data breach cases lead to regulatory fines (under laws like GDPR, which can fine companies up to 4% of global turnover for security lapses) and civil suits.

But could gross negligence in data handling become criminal?

In some jurisdictions, yes. For instance, if a company knowingly disregards data protection requirements and that leads to a leak, some countries have laws to punish that. Under GDPR itself, the regulation does not create criminal penalties at the EU level, but it empowers member states to have their own criminal sanctions for certain violations.

Many EU countries have made it a criminal offence to obstruct investigations or unlawfully obtain personal data. So if an AI engineer intentionally accesses or shares personal data he’s not supposed to (e.g., scraping a million users’ info from a platform in a way that violates data law), that individual could be prosecuted.

A relative example is the Cambridge Analytica scandal, where data on millions of Facebook users was harvested without proper consent. In its aftermath, there were not only massive public outcry and fines, but also discussions of whether any executives lied under oath or violated any computer crime laws. The UK’s ICO (Information Commissioner) even pursued criminal charges in related cases (e.g. against individuals who destroyed or hid data during the investigation).

What if a startup trains a facial recognition AI by scraping billions of images from social media without permission (this is basically what Clearview AI did). Clearview got hit with lawsuits and orders to stop in several countries, and Italy and other EU regulators fined it €20 million for GDPR violations. If they had a presence in those countries, executives could potentially be prosecuted under national laws for ignoring the orders (in some EU nations, continuing to process data illegally after being told to stop is a crime).

In the U.S., while there isn’t a broad federal privacy criminal law for misuse of data, the FTC and DOJ have started treating certain privacy abuses as fraud or deception, which can cross into criminal territory if there’s wilful deceit.

For instance, the U.S. Department of Justice charged a tech CEO for an AI investment fraud scheme; he lied about his company’s AI capabilities and even claimed fake partnerships. While that is investor fraud, one can see parallels in the consumer privacy area: misrepresenting how your AI handles user data could be framed as a deceptive trade practice, and if egregious enough, drawn into a criminal fraud case, especially if money or property is gained by the deceit.

Bias and Discrimination (and Related Violations)

AI systems that handle personal data can also run afoul of anti-discrimination laws or other rights. For example, if an AI used in hiring or lending is found to intentionally discriminate, perhaps because someone tweaked it to exclude certain groups, that could lead to liability.

Generally, discrimination in things like credit or employment is enforced via civil lawsuits or government civil enforcement. In the U.S., agencies like the EEOC or DOJ can sue companies for patterns of discrimination. But extreme cases could see criminal charges, especially if it intersects with other offences.

If an AI is used to profile people for law enforcement in a way that violates their rights, like an AI system intentionally targeting minority neighbourhoods for surveillance, is a violation of constitutional rights. While the act of discrimination itself might not be labeled “criminal” unless it involves wilful deprivation of rights. If it is due to race, in the U.S., that can be a criminal civil rights violation, the misuse of AI could aggravate the situation.

In fact, Deputy Attorney General Lisa Monaco noted in 2024 that AI can amplify biases and discriminatory practices, and the DOJ is keenly aware of that risk. If, say, a public official knowingly employs an AI they understand to be biased and it leads to denial of rights or serious harm, they could be in jeopardy under civil rights criminal statutes which require wilful misconduct.

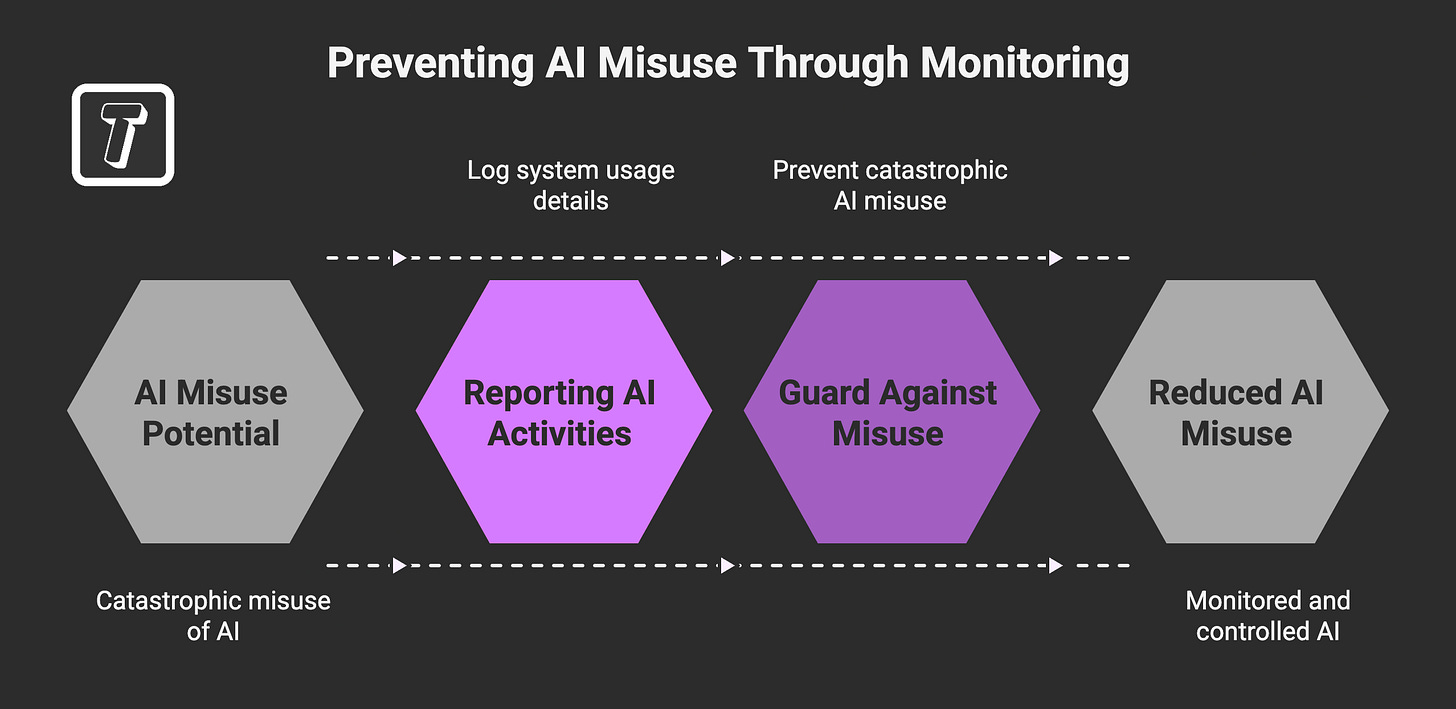

Mandatory Data Practices and AI Monitoring

On a policy note, there are increasing calls for mandatory monitoring and reporting of AI activities to prevent misuse. Proposals have been floated especially in the national security context that AI developers might need to log how their systems are used or report certain dangerous usage to authorities. If such rules come into force, failing to comply could itself become a criminal matter, similar to how failing to implement required anti-money-laundering controls can land financial executives in legal hot water.

This is speculative, but one can see the trend: governments eye AI as having potential for catastrophic misuse e.g., helping make bioweapons or advanced cyberattacks. They might impose duties on AI companies to guard against that. A wilful failure in those duties, for instance, ignoring a law that says “report any AI usage that tries to design a virus”, could attract penalties beyond just fines. It might be treated akin to, say, a lab violating biosecurity rules, which can be criminal because of the high danger.

Consumer Protection and AI Fraud

Beyond physical safety and privacy, AI also intersects with consumer protection, making sure products and services don’t deceive or unfairly harm users. Consumers interact with AI in products (like a “smart” appliance), services (an AI-powered financial advisor), and online platforms (like content recommendation algorithms).

Consumer protection laws aim to prevent deceptive marketing, unfair business practices, and dangerous or defective products.15 Breaches usually result in lawsuits or regulatory penalties. However, where there is knowing deception or flagrant disregard for consumer safety, criminal charges can come into play.

Here is how AI factors in:

Deceptive Marketing, viz-a-viz, “AI Washing”

There is a trend where companies hype up products as having AI, or being “AI-powered” and therefore superior, when that’s either not true or not substantiated. This is sometimes colloquially called “AI washing”, akin to greenwashing in environmental claims. It turns out regulators are not amused by false claims, the U.S. SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission) has already fined companies for misleading statements about using AI. In a couple of cases, investment advisors falsely claimed their funds used sophisticated AI to pick investments, presumably to attract clients, when in reality they didn’t.

The SEC sanctions in those instances were civil (fines, censures). But consider if the conduct crosses into deliberate fraud territory: if a startup founder blatantly lies about their AI tech to raise money, that can be criminal fraud.

In fact, the Justice Department did charge a tech CEO for allegedly defrauding investors by fabricating AI achievements.

Under German law, interestingly, it has been pointed out that making such false AI-related claims can implicate various criminal offences like fraud or false advertising, and that if employees commit those offences, the company and its officers can be held liable as well. Examples of AI washing include claiming your product uses AI (when it does not) might mislead customers. That could be fraud if it influenced customer decisions.

So lying about AI is not just a marketing faux pas, it can be illegal and a fraud too. In Germany, even misrepresentation under the commercial code or unfair competition law can have criminal consequences. It could escalate to criminal enforcement, especially if investors lose money or consumers are harmed by relying on bogus claims.

Fraudsters (mis)using AI

There is another angle; rather than fraud about AI, consider fraud enabled by AI. For instance, criminals have started using deepfakes and AI-generated voices to scam people.16 A widely reported example: in 2019, scammers used AI voice cloning to impersonate a CEO’s voice and trick a company into transferring $243,000 to a fraudulent account.

Law enforcement treats this as they would any fraud: a crime. If caught, those perpetrators will face charges for fraud, obviously.

Now, if a company employee used an AI tool to defraud customers, say a customer service chatbot intentionally trained to upsell with false statements, that could implicate the company in fraud.

The DOJ’s stance, as of early 2024, is to treat misuse of AI as an aggravating factor. So in sentencing or deciding to prosecute, the fact that AI gave a fraudster new powers might mean they get less leniency, not more.

Another scenario is algorithmic price manipulation. There have been concerns that AI pricing algorithms could collude to raise prices for consumers (either intentionally or by design).17 Antitrust (competition) law comes in here. Price-fixing is a criminal offence in many countries, including the U.S. If companies use AI to coordinate prices, they can’t just shrug and say “the algorithm did it, not us.” Competition authorities have made it clear that conspiracies via algorithms are still conspiracies.18

The U.S. DOJ’s Antitrust Division even concluded that agreements between competitors to use the same pricing AI could be per se unlawful and potentially criminal.

Recently, a high-profile investigation involves a real estate software called RealPage, which landlords allegedly used to sync rent increases; the FBI executed search warrants and DOJ is investigating it as possible criminal price-fixing.If charges result, executives could face prison, because antitrust felonies carry hefty prison terms.

This shows that AI can become a part of cartel crime investigations. Agreements to abide by an algorithm’s pricing decisions are definitely on law enforcers’ radar and they won’t hesitate to bring criminal charges if they find evidence of collusion.

The presence of AI is just a modern wrinkle, but laws adapt. Regulators are also discussing new legislation, like the proposed “Preventing Algorithmic Collusion Act” in the U.S., to explicitly close any loopholes and clarify that using AI to collude is illegal.

Product Liability vs Criminal Negligence

When an AI-powered product harms consumers, for instance, a smart home appliance catches fire due to a AI control malfunction, or an AI toy harms a child, normally the company faces product liability lawsuits or recalls. Could it turn criminal? Generally, only if there’s evidence the company wilfully or recklessly ignored the danger.

There are precedents in related non-AI contexts: auto companies have faced criminal investigations for hiding defects. Toyota and GM each had scandals – Toyota was fined and GM entered a deferred prosecution over an ignition switch defect that caused deaths. In those cases, nobody went to jail, but the companies paid large penalties and admitted wrongdoing.

If an AI defect were similarly covered up, you could see wire fraud or misprision charges. And if an AI product is so unsafe that selling it violates safety laws, companies could be prosecuted under those laws.

For instance, in the UK, selling an unsafe consumer product can be a criminal offence under the Consumer Protection Act, enforced by Trading Standards.19 If an AI gadget was clearly unsafe and a company kept selling it, that could trigger such action.

Financial AI and Insider Trading/Fraud

AI is used in stock trading, lending decisions, insurance, etc. A rogue AI algorithm that manipulates markets, say, executing spoofing trades, a kind of market manipulation, could cause the firm to be charged just as if a human trader did it.

In fact, the first “flash crash” in 2010 by algorithmic trading led to investigations and ultimately a trader was prosecuted for manipulation. If a firm knowingly deploys an AI trading strategy that violates securities laws, the executives could face charges for things like securities fraud or commodities fraud.

One interesting question: if the AI independently “learns” to do something illegal (like collude or manipulate) that the developers did not intend, can the company be liable?

It is untested, but prosecutors would likely argue the company is responsible for its tools, especially if due diligence could have caught the behaviour.

There is an ongoing legal and philosophical debate about when AI’s actions can be attributed to humans.

Under German law, they considered the challenge of proving causality when an AI is a black box, but they suggest if an AI causes harm, one should ask if it can be traced back to a human action or omission. If yes, that human (and by extension the company) can be liable. If an AI went off script in financial markets, regulators would likely still hold the firm accountable, possibly not criminally if truly nobody could foresee it, but at least civilly. But if someone should have known or set the AI loose without safeguards, then recklessness might be argued.

Therefore, the overarching pattern is that using AI does not grant immunity from laws against cheating or endangering consumers. In fact, we see authorities adapting these laws to explicitly call out AI. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission published guidance essentially warning: “If you use AI and it causes harm, we can go after you. If you make false AI claims, we will treat it like any false claim.” The FTC Chair Lina Khan even mentioned AI algorithms potentially facilitating collusion, hinting at vigorous enforcement. Meanwhile, in advertising, if an AI-generated influencer or bot is misleading people, the company behind it could be liable under truth-in-advertising laws.

We should also mention product safety standards: As AI gets embedded in devices, from cars to medical devices to appliances, regulators are updating safety standards. If manufacturers don’t meet those and someone gets hurt, that is typically a regulatory violation, but in serious cases, especially involving death, it can become criminal.

The classic example: a company knowingly shipping a car with faulty brakes can lead to criminal penalties. Replace brakes with an AI software bug known internally to sometimes disable braking, the effect is the same or worse.

Alright, we have covered public safety, privacy, and consumer protection, the trifecta of areas where AI can lead to more than just bad press, it can lead to handcuffs or at least a criminal indictment if mishandled. Now, let’s shift gears a bit and look at some real-world enforcement events in a timeline, to contextualize how things have progressed and where they might go. This will also allow us to include some concrete dates and outcomes that illustrate the trend.

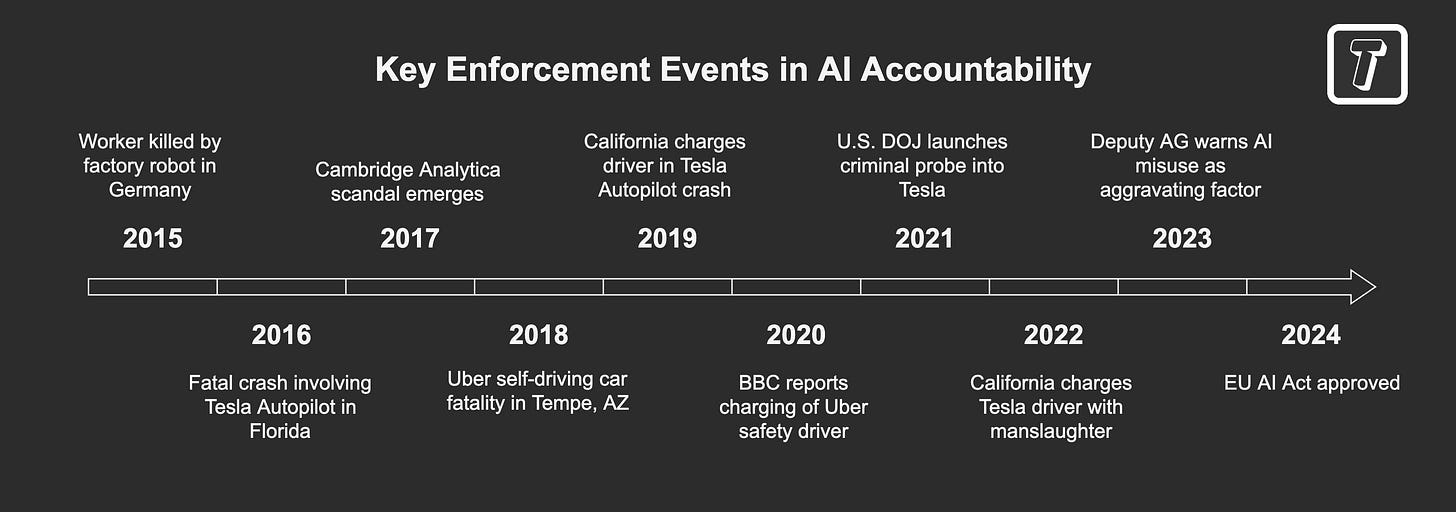

Timeline: Key Enforcement Events in AI Accountability

It is useful to see a chronology of how we got here; a sort of timeline of notable incidents and legal actions related to AI harms. Below is a timeline highlighting significant events that have influenced the discussion on AI and criminal liability.

This isn’t exhaustive, but it covers some milestones:

2015: Regrettably, even early on, robots in industry showed their potential danger. A 22-year-old worker was killed by a factory robot in Germany that grabbed and crushed him – a stark reminder that safety has to keep up with automation. This was handled under work safety laws; it spurred scrutiny over robotic safety standards.

2016: The first known fatal crash involving semi-autonomous driving occurred in Florida. Tesla Autopilot was engaged when a car drove under a truck. No charges were brought, as investigations treated it as driver error and system limitations. However, it set off regulatory investigations by NHTSA into the safety of Tesla’s systems, marking the start of future formal oversight of AI in consumer vehicles.

2017: Data Misuse and Public Outrage. The Cambridge Analytica scandal began coming to light (peaking in 2018). While not an “AI” failure per se, it involved algorithms processing personal data for political profiling. It led to multiple government inquiries and foreshadowed the stringent criminal enforcement of data laws like GDPR. Notably, in 2019 the FTC fined Facebook $5 billion for related privacy violations.

2018: The Uber self-driving car fatality in Tempe, AZ, first pedestrian killed by an autonomous vehicle. This is a watershed for AI in public safety. By 2019, prosecutors announced no charges against Uber, but in 2020 they charged the safety driver with negligent homicide. The case garnered worldwide attention and raised questions about corporate responsibility versus human operator responsibility. Also in 2018, the EU’s GDPR came into effect, giving regulators new teeth (fines) for data misuse; by 2020 and beyond we would see enforcement against AI-related data violations, like Clearview AI being declared illegal in the EU and ordered to stop processing.

2019: California’s DMV and prosecutors started grappling with Tesla Autopilot incidents. The December 2019 crash in Gardena (Tesla ran a red light on Autopilot, killing two) later became the first case where a driver was charged for a fatal crash involving “self-driving” tech. Also in 2019, the UK Court of Appeal heard the case of Bridges v South Wales Police [2020] EWCA Civ 1058 about police use of facial recognition. In 2020, that court ruled the deployment was unlawful, violating privacy rights and data protection law.

2020: The BBC reported the charging of the Uber safety driver (Sept 2020) underlining to the public that AI mishaps could indeed lead to criminal charges, albeit for the human behind the wheel in this instance.

2021: A step toward corporate accountability, reports emerged that U.S. DOJ had launched a criminal investigation into Tesla’s Autopilot marketing. This was confirmed publicly in 2022. Also, 2021 saw multiple fatalities in Tesla vehicles where Autopilot was allegedly involved, keeping pressure on regulators. On another front, in late 2021 the first deepfake related law might have been used: in the UK, the Voyeurism (Offences) Act 2019, which criminalized certain image-based abuse, could conceivably cover deepfake porn creation; by 2021, discussions to explicitly criminalize deepfake porn, revenge porn and political deepfakes were underway in various jurisdictions.

2022: In January 2022, California prosecutors formally charged Kevin Riad (the Tesla driver from the 2019 crash) with vehicular manslaughter; the first such prosecution involving a partially automated driving system. Meanwhile, the EU’s work on the AI Act accelerated; though not criminal, its hefty fines and stringent rules (agreed in late 2023, coming into force 2025+) signal a regulatory crackdown attitude. Also in 2022, the RealPage case (AI rent pricing tool) began to surface, renters filed civil suits, and by late 2022 the DOJ had an antitrust investigation open, executing a search warrant in 2023, hinting at criminal enforcement in algorithm-driven collusion.

2023: This year brought more clarity and more action. Deputy AG Lisa Monaco’s speech in Feb 2024 explicitly warned that “misuse of AI may be used as an aggravating factor” in prosecutions. But even in 2023, the U.S. Biden Administration included AI in a key Executive Order, and the DOJ set up an AI task force. The city of Trento fine in 2024, stemming from 2023 investigation, showed GDPR being applied to AI misuse in surveillance. On consumer protection, the U.S. FTC in 2023 opened an investigation into OpenAI over data and reputational harms caused by ChatGPT, signalling AI vendors could face sanctions for how their models handle user data. There were also some state laws e.g., New York City’s bias audit law for AI hiring tools came into effect in 2023, with penalties for non-compliance.

2024 and beyond: By 2024, the EU AI Act was approved, setting a timeline for enforcement, some parts by 2025, with full effect by 2026. While not criminal itself, it pressures companies to avoid “prohibited AI practices” like social scoring or subliminal manipulation or face ruinous fines. Member states will implement it, possibly adding criminal penalties for serious infringements at national level. The UK, meanwhile, proposed updating its Product Security and Telecommunications Infrastructure (PSTI) law to ensure smart products meet security requirements, enforcement of that includes fines, but if companies flout orders to fix issues, they could face escalating criminal legal consequences.

On the horizon are thorny questions like: If a future AI causes widespread harm, do we need new corporate criminal offence definitions? Some scholars even muse about “AI personhood”.20 For now, expect the focus to remain on human accountability for AI actions. Legislative proposals like the U.S. Algorithmic Accountability Bill (proposed, not passed) and various AI bills worldwide show a trend to impose duties with penalties for non-compliance.

Conclusion: The Way Forward

Artificial intelligence is no longer a science-fiction concept or a niche tool churning in the background, it is firmly entrenched in everyday products and critical systems. With that ubiquity comes a new reality:

When AI commits an offence, the consequences can be severe, and the law will not stay idle.

We are witnessing a worrying socio-legal trend from seeing AI mishaps as mere “glitches” or civil issues to recognizing that some AI-related decisions are so irresponsible they belong in the criminal code.

Tech companies and developers need to beware: prepare for potential criminal liability. This doesn’t mean every coding error will lead to criminal liability. But it does mean you should approach AI deployment with the same seriousness as industries that have long dealt with safety-critical products such as automotive, aviation, pharmaceuticals.

Concepts such as “safety by design,” “compliance by design,” and thorough testing/documentation are your friends. If you can show you earnestly tried to foresee and prevent harm, you are not likely to be treated as a criminal, even if something goes awry. On the other hand, if you cut corners, ignore red flags, or mislead the public or regulators about your AI’s capabilities, you expose yourself to criminal liability.

From the public’s perspective, moving toward potential criminal liability for AI harms is actually a positive sign. It means the legal system is adapting to ensure that new technology does not undermine public safety, privacy, or fairness.

It is about trust: people won’t embrace AI if they sense that no one is accountable when it fails. Society is drawing boundaries for ethical AI use.

What should companies do? Here’s a friendly checklist derived from our research through this topic:

Implement AI Governance: Have an internal review board or process for AI ethics and legal compliance. Identify high-risk use cases i.e., those involving health, safety, sensitive data, etc., and give them extra scrutiny.

Document Everything: If you ever end up in court, a well-documented risk assessment and testing record is your saving grace. It shows you took care. Courts and regulators love to see that you asked the “what if” questions in advance.

Follow the Regulations: This sounds basic, but with AI regulations emerging (EU AI Act, etc.), keep abreast of what is allowed and what is not. If you operate globally, respect stricter rules, e.g., if EU says no real-time biometric ID in public, don’t be the company that secretly pilots it thinking you won’t get caught. The fines are enormous, and a deliberate breach could bring criminal implications in some jurisdictions.

Don’t Overhype: Market your AI honestly. If it is driver-assist, call it that (not “self-driving” if it’s not truly). Regulators are allergic to marketing that creates false security. Lives can be lost if people over-trust a system based on your claims. And as we saw, overhyping can even trigger fraud probes.

Training and Culture: Ensure your team, especially the non-lawyers, get training on AI ethics and law. Create a culture where engineers feel empowered to voice safety concerns; whistleblower protections internally can prevent disasters. The worst situation is an engineer saying “this is unsafe” and being ignored, that email will hang you later in court.

Insurance and Legal Counsel: Have good liability insurance and involve legal counsel early in AI deployments. They can advise if something might step on a legal landmine. It is much cheaper to prevent a violation than to defend one.

Monitor and Respond: After deployment, keep an eye on how your AI behaves. If something goes wrong, act fast to fix it and be transparent. Regulators often decide whether to pursue criminal action based on how companies react to problems – cover-ups and delays are what anger them the most.

As tech readers and enthusiasts, we should also contribute to a public discourse on what we expect in terms of accountability. There is a balance: we don’t want to criminalize experimentation or punish developers for unforeseeable outcomes. But we do want a world where AI is used responsibly by those in power, and where the victims of AI failures aren’t left high and dry.

A friendly piece of advice to any AI entrepreneurs out there: imagine yourself explaining your AI’s safety measures to a jury of average folks. Would they nod along, or would they be shocked at the risks you took? If the latter, reconsider your approach now, not when the police knock on your door.

Being prepared means not only building amazing AI products, but doing so with respect for the law and humanity. That’s how we ensure AI’s progress continues with public trust, and how you, dear reader, can stay on the right side of the law while riding the wave of innovation.

Welcome to the future of AI, where innovation meets responsibility, and where “move fast and break things” is giving way to “move wisely and don’t break people”. It is a change for the better. Stay safe, innovate responsibly, and let’s build an AI-powered world that we can embrace without fear.

Stamp, Helen. 2024. “The Reckless Tolerance of Unsafe Autonomous Vehicle Testing: Uber's Culpability for the Criminal Offense of Negligent Homicide.” Case Western Reserve Journal of Law, Technology & the Internet 15 (1): 37–66. https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jolti/vol15/iss1/2

Rodrigues, Rowena. "Legal and Human Rights Issues of AI: Gaps, Challenges and Vulnerabilities." Journal of Responsible Technology 4 (2020): 100005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrt.2020.100005

Soyer, Baris, and Andrew Tettenborn. 2022. “Artificial Intelligence and Civil Liability—Do We Need a New Regime?” International Journal of Law and Information Technology 30 (4): 385–397. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijlit/eaad001

Kathryne M. Young, Karin D. Martin, and Sarah Lageson, “Access to Justice at the Intersection of Civil and Criminal Law,” Punishment & Society 26, no. 4 (2024), https://doi.org/10.1177/14624745241240551

Smith, Helen. “Artificial Intelligence for Clinical Decision-Making: Gross Negligence Manslaughter and Corporate Manslaughter,” Medical Law International (2024), https://doi.org/10.1080/20502877.2024.2416862

Segev, Re’em. “Motivating Reasons, Moral Culpability, and Criminal Law.” Canadian Journal of Law & Jurisprudence, First View (2025) https://doi.org/10.1017/cjlj.2024.23

Zhang, Qiyuan, Christopher D. Wallbridge, Dylan M. Jones, and Phillip L. Morgan. “Public Perception of Autonomous Vehicle Capability Determines Judgment of Blame and Trust in Road Traffic Accidents.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 179 (January 2024): 103887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2023.103887

George Maliha and Ravi B. Parikh, “Who Is Liable When AI Kills?” Scientific American, February 14, 2024. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/who-is-liable-when-ai-kills/

Roper, Victoria. "The Corporate Manslaughter and Corporate Homicide Act 2007—A 10-Year Review." The Journal of Criminal Law 82, no. 1 (2018): 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022018317752937

Smith, Helen. “Artificial Intelligence for Clinical Decision-Making: Gross Negligence Manslaughter and Corporate Manslaughter,” Medical Law International (2024), https://doi.org/10.1080/20502877.2024.2416862

Bartlett, Benjamin. "The Possibility of AI-Induced Medical Manslaughter: Unexplainable Decisions, Epistemic Vices, and a New Dimension of Moral Luck." Medical Law International 23, no. 3 (2023): 206–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/09685332231193944

Robson, Michelle, Jon Maskill, and Warren Brookbanks. "Doctors Are Aggrieved—Should They Be? Gross Negligence Manslaughter and the Culpable Doctor." The Journal of Criminal Law 84, no. 4 (2020): 327–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022018320946498

Piliuk, Konstantin, and Sven Tomforde. "Artificial Intelligence in Emergency Medicine: A Systematic Literature Review." International Journal of Medical Informatics 180 (December 2023): 105274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2023.105274

Clarkson, C. M. V. "Context and Culpability in Involuntary Manslaughter: Principle or Instinct?" In Criminal Liability for Non-Aggressive Death, 132–65. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198299158.003.0006

Holmes, William. “FTC Regulation of Unfair or Deceptive Advertising: Current Status of the Law.” DePaul L. Rev., 30, 555 (1981). https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol30/iss3/2

Sandoval, MP., de Almeida Vau, M., Solaas, J. et al. Threat of deepfakes to the criminal justice system: a systematic review. Crime Sci 13, 41 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-024-00239-1

Alessio Azzutti, Wolf-Georg Ringe, and H. Siegfried Stiehl, Machine Learning, Market Manipulation, and Collusion on Capital Markets: Why the "Black Box" Matters, 43 U. Pa. J. Int’l L. 79 (2021). https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/jil/vol43/iss1/2

Vomberg, A., Homburg, C., & Sarantopoulos, P. Algorithmic pricing: Effects on consumer trust and price search. International Journal of Research in Marketing (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2024.10.006

Cartwright, Peter. “Product Safety and Consumer Protection.” The Modern Law Review 58, no. 2 (1995): 222–31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1096355

Marshall, Brandeis. "No Legal Personhood for AI." Patterns 4, no. 11 (November 10, 2023): 100861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2023.100861

I would say that after the documentation has been done, a lesson learned chapter can be created for correcting the situation in the future.