A Victory for Privacy as German Court Bans Tricky Consent Tactics Used by Big Tech (Bavarian Pharmacists’ Association v. Dutch Mail-Order Pharmacy)

Newsletter Issue 7 (Case Report): Germany’s highest civil court has ruled that bundling user consent with actions like clicking “Play” violates GDPR.

Tired of apps sneaking off with your data the moment you click “Play”? Germany’s BGH court just called time on that shady game. In a major win for privacy, the court ruled that Meta’s old App Centre tricks violated GDPR. Here’s why this matters, and what it means for digital consent going forward.

German Court (BGH) Upholds GDPR Consent Rules: No More Sneaky “Play to Agree”

In a victory for user privacy and transparency, Germany’s Federal Court of Justice (BGH), the highest court for civil and criminal matters, has delivered a major ruling reinforcing core principles of the EU’s GDPR.

The case in question involved Meta (Facebook) and its App Center, and whether Facebook obtained valid consent from users to share data with third-party apps.

The BGH’s answer: No, it did not because users were not properly informed or asked. The ruling, issued on March 27, 2025, confirms that bundling consent with actions like clicking “Play” without clear disclosure violates the GDPR’s requirements for informed, freely given consent. It’s also significant because it affirms that consumer associations can sue over GDPR breaches, not just regulators, a boost for collective enforcement of privacy rights.

The origins of this case go way back to 2012, when the Federation of German Consumer Organisations (vzbv) sued Facebook over its App Center practices. In Facebook’s App Center, users could find free games and apps (think FarmVille et al. back in the day).

When a user clicked “Play Now” on a game, Facebook would automatically share the user’s data (like their name, email, friends list, etc.) with the game developer and allow the app certain permissions. There was a small notice stating that by clicking, the user agrees to this data transfer. But there was no separate consent checkbox or detailed info upfront. Essentially, “By clicking Play, you agree we give your data to this app”.

Post-GDPR (which came into effect in 2018), this practice was clearly dodgy. The case eventually led to a question for the European Court of Justice (CJEU) on whether consumer bodies could bring such privacy lawsuits.

The CJEU in July 2024 said yes, consumer orgs can sue over GDPR breaches (even without a specific data subject’s mandate) if it involves infringement of rights (Case C- 757/22). Armed with that, the BGH proceeded to rule on the substance.

The BGH’s findings were scathing for Meta’s practices:

Facebook “violated the GDPR with its app centre for free games”, said the court bluntly. Specifically, it breached Articles 12 and 13 GDPR, which are about transparent information provision to data subjects. Article 12 says info must be given in a concise, transparent, intelligible form. Article 13 lists what information must be provided when personal data is collected, like the purpose of processing, data recipients, and legal basis.

The user “was not initially informed about the type, scope and purpose of the collection and use of personal data in a generally understandable form”, nor about the legal basis or who the data would go to. That quote from the BGH is practically a checklist of GDPR Article 13 requirements, which Facebook failed to meet. They did have a notice, but it was deemed insufficient and not user-friendly (probably buried in fine print that vanished once you clicked).

Worse, the way consent was obtained was effectively bundled and opaque. The BGH pointed out the “stumbling block”: by clicking “Play”, users were unknowingly giving permission for extensive data access. This was not an affirmative, unambiguous consent to specific data processing, it was more like a trick or “consent by ambush”. GDPR requires consent to be a clear affirmative act, informed, specific, and freely given (Article 7 GDPR). The court found Facebook’s method failed all those: it wasn’t clear or specific (user just wanted to play a game, not consciously consent to data sharing), and arguably not freely given because if you wanted to play, you had no choice but to submit to the data sharing.

The BGH also tied this to the principle of fairness (Article 5(1)(a) GDPR) and even Germany’s unfair competition law (UWG). It said withholding essential info from users was “a violation of the principle of fairness” under UWG §5. This cross-pollination with consumer protection law is interesting: using personal data without proper info can be considered a misleading business practice. The court emphasized that given the “economic importance of personal data for internet businesses”, information duties are “of central importance.” Users must be informed “as comprehensively as possible” about the scope and implications of consent to make an informed decision. In other words, the more valuable and sensitive the data, the greater the duty to be crystal clear with people.

What does this mean going forward?

For one, Meta (and other platforms) can’t do sneaky consents via a single button for multiple actions. After this saga, Facebook no longer does “instant personalization” or auto-sharing in the same way (they’ve reformed many practices under regulatory pressure).

But the ruling cements that such designs are illegal. Meta might face claims for old practices, but importantly it sets a bar for any future endeavors: if they launch new integrated services, they must keep privacy disclosures front and center and separate from mere use of service.

Secondly, consumer advocacy groups have a green light in Germany (and by CJEU, across the EU) to sue companies over privacy. This is big. It means GDPR enforcement isn’t only in the hands of data protection authorities (DPAs); consumer bodies can act as an additional enforcer, especially for matters that also smell of consumer law violations (e.g., misleading consents, unfair contract terms regarding data).

We might see more such lawsuits. For example, a consumer group might sue a streaming service for a convoluted privacy policy or default settings that slurp up too much data. The BGH ruling affirmed that such groups have standing. This increases compliance risk for companies – you’re not just waiting for a regulator’s investigation; an NGO might drag you to court too.

The case also highlights the synergy between data protection and consumer protection laws. Here, an unfair competition law (UWG) claim paralleled the GDPR issue. In Europe, we see a movement to treat personal data protection as a consumer right. Courts and regulators might use both legal frameworks to punish egregious behaviour.

For businesses, that means a privacy violation can also trigger fines or remedies under consumer laws (which might include injunctions or damages via civil suits).

It’s a one-two punch: GDPR fines from authorities and potential lawsuits from consumer associations or competitors (yes, competitors – BGH also in another case said competitors can sue if a rival gains advantage by violating data laws).

In practical terms, what should companies do?

Ensure clear, upfront disclosures and separate consent for any data sharing that isn’t obviously part of the user-requested service. If your app wants to access a user’s contacts for friend-finding, don’t hide that behind a generic “Start” button; present a clear opt-in with an explanation. The BGH’s stance is that users shouldn’t be surprised about what will happen with their data.

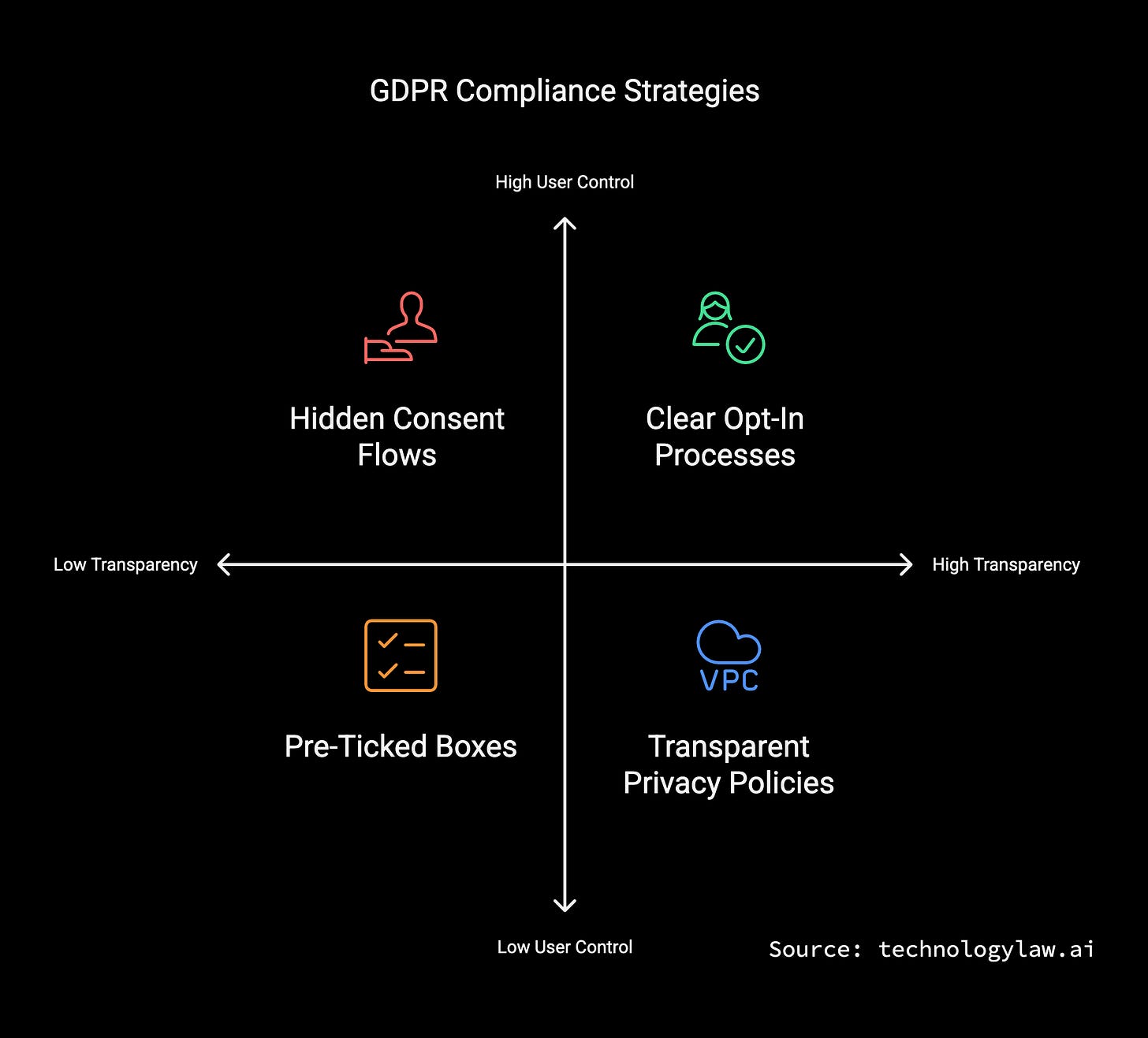

No pre-ticked boxes, no “by the way” consents. The days of “By using this site, you agree to our privacy policy [that allows lots of stuff]” are over – at least in Europe. Consent requires an action (ticking a box, clicking a specific agree button) after being informed. In the Facebook case, simply playing a game was misconstrued as consent; that’s not valid. Design UX such that consenting to data use is a distinct action from just engaging with core functionality.

Transparency in plain language: The BGH noted info wasn’t in a “generally understandable form”. Tech companies must write user-facing notices in simple terms. If you need to convey “This game will receive your public profile, friend list, and email, and can post on your behalf,” say exactly that in a prominent way. Jargon or burying it in Terms of Service that no one reads won’t fly. Regulators and courts often use the perspective of an average user. If your grandma or little brother wouldn’t quickly grasp what they’re allowing, you probably need to rewrite it.

The ruling also, by resolving a long-running case, shows the GDPR has teeth even years later. A lawsuit from 2012, updated to GDPR standards, resulted in a decisive outcome in 2025.

Companies might have thought older practices are water under the bridge, but if they continued post-2018, they could still be called to account.

It’s a bit of a warning shot: fix your dark patterns and dubious consent flows now, or you might face a legal challenge down the line, even if regulators haven’t gotten to you yet.

For users and society, this decision is reassuring. It reiterates that “free” services can’t trick you into giving up personal data without you really knowing. Just because you click something in a hurry to use an app doesn’t mean the company can grab your data and run.

Consent isn’t a one-time checkbox buried in a sign-up flow; it’s an ongoing obligation to treat users fairly and openly. As the BGH eloquently put it, users must be able to make an informed decision about their data. That’s exactly what GDPR intended, and the courts are making sure it’s honored.

Interestingly, this case was also about competitive advantage; Facebook gained an edge by making sign-on so seamless at the expense of privacy. The BGH referenced the economic importance of data. In a sense, hiding the “cost” (your data) was an unfair business practice. So aligning privacy compliance goes hand-in-hand with fair competition too.

What about the jurisdictional impact?

It’s largely EU-internal, but it shows Germany’s courts aligning tightly with EU Court guidance. It sets a precedent likely to be influential in other EU countries facing similar issues. Big tech often argues for a uniform EU approach (to avoid stricter rules country-by-country).

Here, we see exactly that: German judges applied EU law vigorously, and consumer groups EU-wide will cite this case. So while it’s a German ruling, it effectively raises the bar for any company operating in Europe.

For tech founders globally, the message is clear: consent and transparency aren’t just formalities, they are fundamental rights for users. Good privacy compliance isn’t just about avoiding fines; it’s about respecting your users, which in turn builds trust and loyalty.

If you find yourself wondering “Can we just include this in the terms and assume users consent?”, stop and think of this case. It’s better to design a user experience that asks openly and gives people a real choice. Yes, some may opt out and you lose some data advantage, but forcing them without proper consent is not a sustainable (or legal) strategy.