Investor Guide: The Hidden Legal Issues That Will Undercut Nvidia's Share Price

Nvidia is powering global AI revolution, but beneath the infrastructure are legal battles, global risks, and hidden investor opportunities.

Nvidia products are being utilized by many global organisations for AI infrastructure. Behind its meteoric rise lies a complex web of legal risks, from antitrust investigations to export bans that could shake its future outlook. At the same time, Nvidia’s dominance in AI chips offers massive rewards for investors who understand what is really at stake. In this deep dive, we break down the biggest legal forces impacting Nvidia’s future, and what they mean for your money as an investor.

Is Nvidia Really a Safe Bet for Retail Investors?

Nvidia’s meteoric rise in the age of artificial intelligence has created extraordinary opportunities for investors, and a tangle of legal and regulatory questions.

The company sits at the intersection of surging demand for AI chips and intensifying scrutiny from governments worldwide.

In this deep dive, we explore eight key themes that combine both the growth rewards and the legal risks of investing in Nvidia.

Each theme highlights a specific area of Nvidia’s expansion offering potential returns, paired with a critical analysis of the associated legal or regulatory risks from the U.S. and international markets.

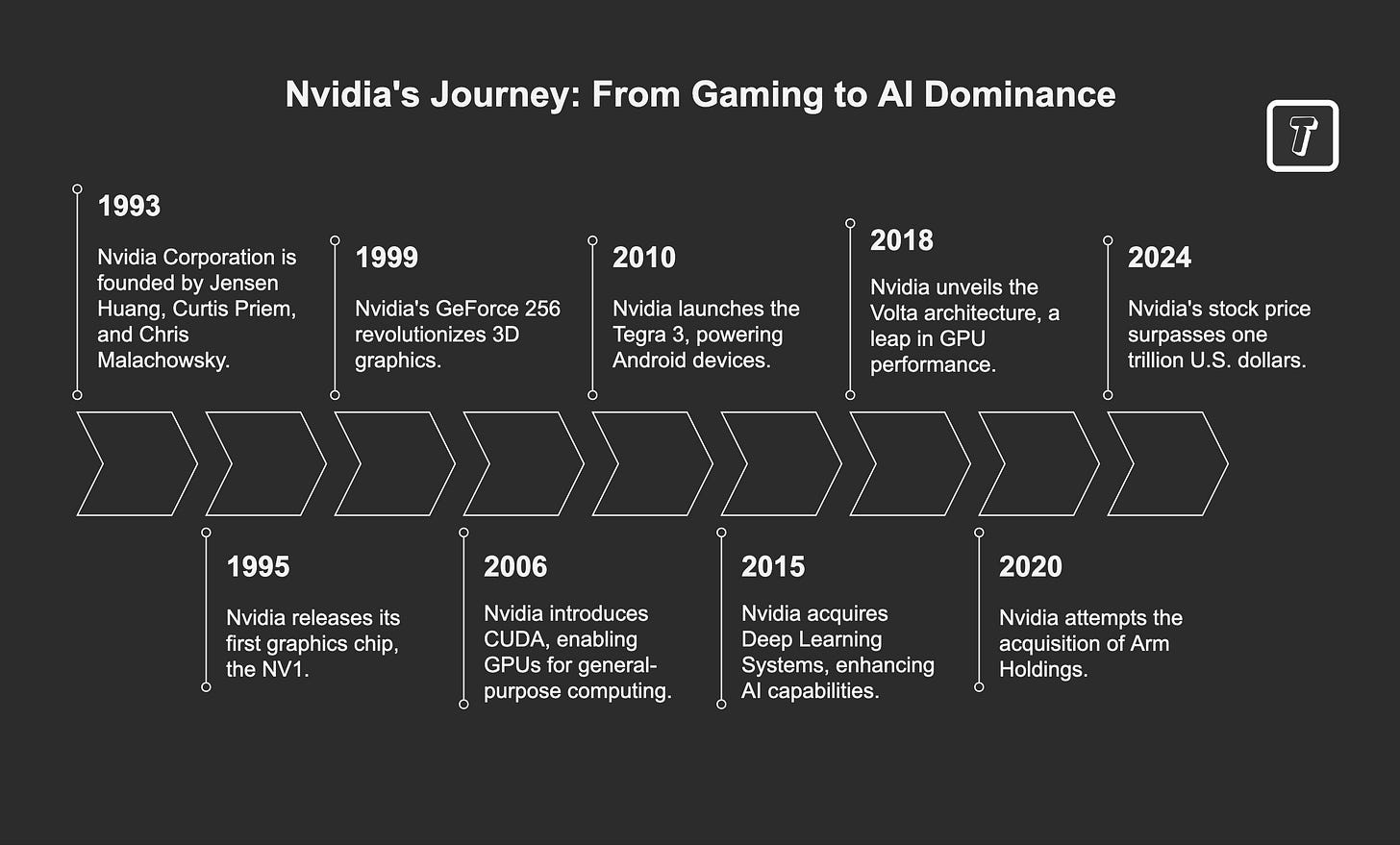

Nvidia has become synonymous with the AI revolution, powering everything from advanced research labs to popular consumer tools like ChatGPT. In 2023–2024, surging demand for Nvidia’s AI chips sent its stock and valuation into the stratosphere.

The company’s market capitalization briefly topped $2 trillion in early 2024, less than nine months after it first crossed the $1 trillion mark. In one record-breaking day, Nvidia’s value jumped by $277 billion following a blockbuster earnings report, the largest single-day gain in Wall Street history.

Such eye-popping figures illustrate why many retail investors are captivated by Nvidia’s growth story and its dominant position in artificial intelligence. However, alongside these rewards lie serious legal and regulatory risks that could impact Nvidia’s future.

U.S. and European authorities are scrutinizing the company’s market power, international trade tensions threaten key markets, and Nvidia’s heavy reliance on certain suppliers presents strategic vulnerabilities.

This deep dive will break down why Nvidia dominates the AI chip market, examine the legal risks that could affect its valuation, explore the growth prospects and rewards for investors, and offer practical guidance on how to evaluate Nvidia’s risks and rewards.

1. AI Data Center Gold Rush vs. Regulatory Scrutiny

Nvidia’s data centre business is booming on the back of an AI gold rush. The company’s GPUs have become essential for training large-scale machine learning models, driving unprecedented revenue growth.

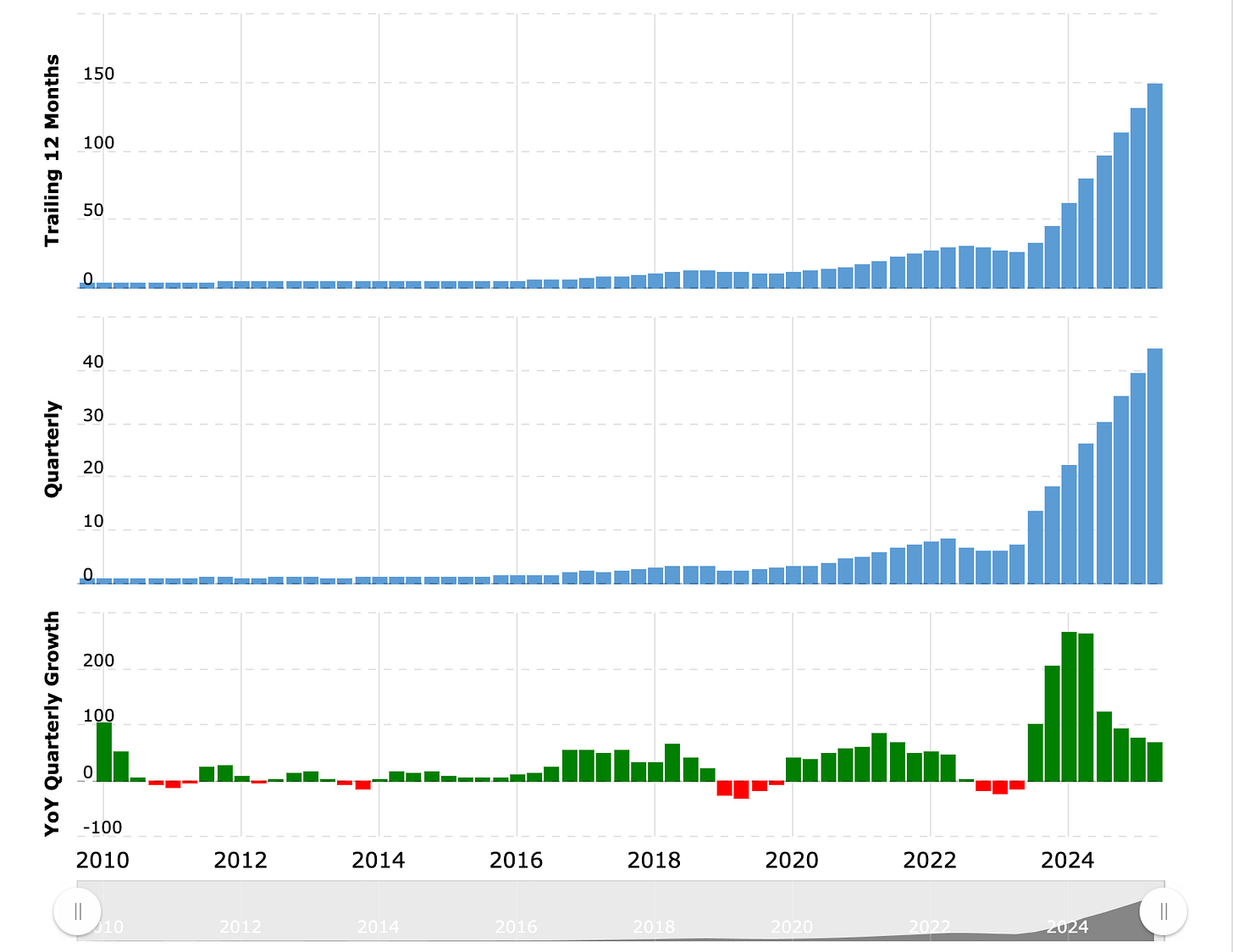

In the first quarter of fiscal 2025 alone (Feb–Apr 2024), Nvidia reported a record $26 billion in revenue, up 262% year-on-year, with its data centre segment contributing $22.6 billion, about 87% of total revenue.

This surge, fuelled by demand for AI acceleration in cloud computing, has made Nvidia the de facto supplier for “AI factories” in tech giants and enterprises alike.

Such dominance positions investors for handsome rewards as Nvidia’s chips become the picks and shovels of the AI revolution.

The company’s annual sales more than doubled from $27 billion in 2023 to $60.9 billion in 2024, and are projected to more than double again to roughly $130 billion in 2025, explosive growth by any measure.

Yet the very scale of this success is drawing regulatory scrutiny. When one company commands an outsized share of a critical tech market, lawmakers take notice.

In Nvidia’s case, its near-monopoly in high-end AI GPUs, an estimated 84% market share, far ahead of competitors, has prompted questions from antitrust authorities around the world. U.S. regulators have kept an eye on Nvidia’s market power, the FTC famously intervened to block its attempted ARM acquisition: more on that later, and now EU regulators have launched inquiries into Nvidia’s business practices.

In late 2024, the European Commission sent questionnaires to Nvidia’s customers and rivals probing whether the company bundles its GPUs with other products or imposes restrictive conditions, potentially abusing its dominance.

Similar scrutiny is reportedly underway in the UK, China, and South Korea. For investors, this means that while Nvidia’s data centre dominance is a major profit driver, it also carries the risk of regulatory action, from fines (EU antitrust penalties can run up to 10% of global turnover) to behavioral remedies that could curtail Nvidia’s freedom in contracting with customers.

Retail investors should cheer Nvidia’s AI-fuelled financial performance, after all, few companies are posting triple-digit growth, but also monitor the tone of regulators.

Thus far, no formal antitrust charges have been filed in the U.S. or EU regarding Nvidia’s sales practices, apart from merger reviews.

However, early warning signs like the EU’s questionnaire about GPU and networking product tying suggest a risk of future investigations. Investors would be wise to follow developments such as the antitrust authority’s ongoing investigation.

Any enforcement action could introduce volatility.

While it’s unlikely that regulators would break up Nvidia or cap its data centre market share, potential outcomes could include fines or requirements to ensure fair access for competitors, for example, not locking customers into Nvidia’s ecosystem.

2. Export Controls and the China Factor

No discussion of Nvidia’s prospects is complete without examining China, both as a huge growth market and as a source of legal risk via U.S. export controls.

On one hand, China’s tech companies and research institutions have an insatiable appetite for Nvidia’s AI chips, representing a major opportunity.

On the other hand, U.S. national security policy has increasingly restricted Nvidia’s ability to capitalize on that demand, turning China into a minefield of regulatory compliance issues.

China has historically been a significant end-market for Nvidia’s GPUs, from data centre accelerators to high-end gaming cards. Even after initial U.S. export curbs in 2022, Chinese firms continued to seek Nvidia through alternative channels.

For instance, prior to the latest restrictions, Nvidia commanded roughly 90% of China’s AI chip market. This implies that, absent export barriers, China could contribute materially to Nvidia’s revenue and growth.

Nvidia has attempted to navigate restrictions by developing slightly toned-down versions of its flagship products for China, notably the A800 and H800 GPUs, which were modifications of the A100/H100 designed to meet earlier U.S. rules.

These sales to China were lucrative and helped serve pent-up demand (indeed, Chinese buyers reportedly paid a premium on the grey market; for example, an A100 chip costing $10,000 elsewhere could fetch over $22,000 in China under the ban). In essence, if geopolitical tensions eased, Nvidia stands to unlock a wave of deferred Chinese demand, a tantalizing reward for investors.

The U.S. government views advanced AI chips as “strategic dual-use” technologies and has moved aggressively to block China’s access to Nvidia’s top-end GPUs. In October 2022, Washington banned Nvidia’s A100 and H100 chips from being exported to China (including Hong Kong), citing national security concerns. Nvidia complied by halting those sales and introduced the A800/H800 as workarounds. However, by October 2023, the U.S. closed that loophole too – extending the ban to Nvidia’s slower A800 and H800 models that had been developed for China.

Then in 2024, rules tightened further: the U.S. Commerce Department informed Nvidia that even its upcoming “H20” series, a new high-memory-bandwidth chip, would require a special export license for China “for the indefinite future”, effectively a ban unless exemptions are granted. This escalation had an immediate financial impact; Nvidia disclosed it expects up to $5.5 billion in charges due to the inability to sell H20 chips in China, accounting for inventory and purchase commitments that now have no market.

For investors, this is a stark reminder that policy decisions can directly impact the bottom line. Nvidia’s share price has swung on export control news in the past e.g. a 5% drop when new chip rules were announced, reflecting how material the China risk is.

These export controls are part of a broader U.S.-China “tech decoupling.” Allies like the Netherlands and Japan have joined the U.S. in restricting semiconductor equipment (ASML’s lithography tools, for instance) to China, which indirectly affects Nvidia by slowing China’s ability to fabricate advanced chips domestically. China, for its part, has protested the chip bans and could retaliate e.g. by restricting exports of critical minerals.

It is a volatile geopolitical backdrop that investors must factor in. Notably, the U.S. rules target not just direct exports by Nvidia, but also any third-party shipments and even cloud services providing access to Nvidia GPUs in China. This creates a complex compliance environment; Nvidia must exercise strong oversight to avoid unauthorized diversion of its products to blacklisted Chinese entities.

For retail investors, Nvidia’s China conundrum means balancing growth potential with regulatory risk. In the short to medium term, one should assume that sales of cutting-edge Nvidia chips to China will remain heavily curtailed. Nvidia is responding by redirecting supply to other regions (the global AI demand is so high that unsold China-bound chips can often find buyers elsewhere) and by lobbying for nuanced rules.

CEO Jensen Huang has publicly argued that blanket GPU export bans may be counterproductive and that Nvidia can provide less-powerful versions that meet security guidelines. However, investors should be prepared for continued headlines about export licenses and sanctions.

A key strategy is to watch Nvidia’s earnings disclosures and guidance: the company now regularly quantifies the expected impact of export curbs (like the $5.5B H20 charge); use these as inputs to gauge how much of Nvidia’s valuation hinges on China.

In portfolio terms, factor in that Nvidia’s access to the world’s second-largest economy is not guaranteed but at the mercy of U.S. policy. Diversification or hedging can mitigate portfolio volatility related to these geopolitical moves.

In summary, China represents a huge “what if” upside for Nvidia that is, for now, constrained by law – investors should stay alert to any changes (tightening or loosening) in export regulations, as they will directly influence Nvidia’s growth trajectory and stock swings.

3. Market Dominance and Antitrust Scrutiny

Nvidia’s dominant market position has been a boon for profits – but it also puts a target on the company’s back when it comes to antitrust and competition law. From the United States to Europe and Asia, regulators are wary of any single company wielding too much power in the semiconductor and AI ecosystem. For Nvidia, the past few years have illustrated both the upside of market leadership and the legal challenges that come with it.

Nvidia’s near-unchallenged lead in advanced GPUs means it enjoys considerable pricing power and customer lock-in. Its proprietary CUDA software platform has become the industry standard for GPU computing, making it hard for would-be competitors to lure away Nvidia’s developer base. For investors, this has translated into high margins and sustained demand. When a company controls the “must-have” product in a burgeoning industry (akin to an Intel in the PC era or a Microsoft with Windows), it can reap outsized rewards.

Nvidia’s data center gross margins are notably strong, and clients often have little choice but to accept Nvidia’s product bundles (GPUs paired with Nvidia’s networking hardware, for example) to get the best performance. This ecosystem control is a strategic moat that boosts long-term investment returns, if it remains intact.

Antitrust regulators globally have already flexed their muscles where Nvidia is concerned. The most dramatic example was Nvidia’s attempted $40 billion acquisition of Arm Ltd., a UK-based chip IP designer, which was terminated in early 2022 after facing “insurmountable regulatory hurdles” on multiple continents. U.S., UK, EU, and Chinese authorities all raised serious concerns that Nvidia owning Arm (whose technology is used by hundreds of companies, including Nvidia’s rivals) would distort competition.

The U.S. FTC went so far as to sue to block the deal, calling it an “illegal vertical merger” that could give Nvidia too much market power over rival chipmakers. In the end, Nvidia had to abandon the acquisition, pay a $1.25B breakup fee, and settle for being just a customer/partner of Arm rather than its owner.

While that specific outcome removed the potential upside of Nvidia controlling Arm’s valuable IP, it also avoided a protracted legal battle. The lesson is clear: regulators are willing to intervene even against blockbuster deals, and Nvidia’s future M&A ambitions will face heavy scrutiny if they appear to threaten competition.

Beyond mergers, Nvidia’s day-to-day business practices are under the antitrust lens as well. We noted above the EU’s investigation into whether Nvidia bundles products or ties sales in anti-competitive ways. To give more detail: Brussels officials are asking data centre customers if Nvidia made GPU sales conditional on also buying Nvidia’s high-performance networking (a segment Nvidia entered by acquiring Mellanox). They are effectively probing if Nvidia is leveraging one monopoly (AI chips) to boost another part of its portfolio, which could shut out networking rivals.

Meanwhile, the French Competition Authority opened an inquiry in 2023 specifically into Nvidia’s dominance in the graphics/AI chip market, and reports suggest it is preparing formal charges.

In the U.S., while there’s no public antitrust case against Nvidia’s current practices, regulators have shown interest in the AI chip space generally; Lina Khan (FTC Chair) has cited the Nvidia-Arm saga as a victory that “protected innovation,” and the FTC has also looked at smaller Nvidia deals (such as its proposed $70M purchase of software firm Run:ai) via referrals from abroad. Even China’s antitrust authority has a say; it was one of the jurisdictions that never approved the Arm deal (effectively vetoing it), and it could scrutinize Nvidia if, say, Chinese GPU startups complain of unfair tactics.

Nvidia’s market dominance is a double-edged sword. In the near term, it implies strong pricing and growth, a positive for the stock. But one should bake in a risk premium for potential legal challenges. Antitrust processes tend to be lengthy, so even if an investigation ramps up, it might be years before any resolution (as seen with big tech antitrust cases). This means any immediate stock impact will likely come from news flow (e.g. announcements of investigations or lawsuits) rather than sudden operational changes.

A savvy investor will keep tabs on regulatory news: for example, if the EU were to formally charge Nvidia or the FTC were to announce a case, that could knock the stock due to uncertainty. Conversely, the absence of any major antitrust case in the next couple of years would be a green light that Nvidia can continue business-as-usual.

It is also worth noting what antitrust “remedies” could look like: in extreme cases, regulators can impose fines (the EU’s max 10% of revenue penalty looms large, which could be over $10 billion given Nvidia’s sales) or require behavioural changes (like no forced bundling, or even mandated licensing of certain technologies to competitors on FRAND terms). Structural break-up of Nvidia is highly unlikely in the current political climate, but not impossible if decades down the line it’s seen as critical infrastructure monopoly.

4. Supply Chain Dependencies on TSMC, ASML, and Arm

While Nvidia is often lauded for its innovation and market savvy, its success also hinges on a few critical partners and suppliers. The company heavily relies on third parties for production and essential technology. This presents a mix of rewards (access to world-class capabilities without heavy capital investment) and risks (exposure to geopolitical and supplier-specific issues outside Nvidia’s direct control).

The key pillars of Nvidia’s supply chain are Taiwan’s TSMC for chip fabrication, the Netherlands’ ASML for lithography technology (through TSMC), and the UK’s Arm Ltd. for CPU intellectual property.

TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co.)

Nvidia’s most advanced GPUs (like the A100, H100, and the upcoming Blackwell generation) are manufactured by TSMC, which is the only foundry currently capable of mass-producing at the bleeding-edge process nodes (5nm, 4nm, moving to 3nm).

The reward here is clear: by leveraging TSMC, Nvidia can build chips with unparalleled performance and efficiency, outpacing competitors who lack similar access. It is no exaggeration to say TSMC’s prowess has enabled Nvidia’s AI ascendance; a win-win relationship where Nvidia gets top-notch chips and TSMC gets a huge volume customer.

Nvidia benefits from TSMC’s multi-fab capacity and even plans to source from TSMC’s new Arizona fab in the U.S. once it comes online, to add “diversity and resilience” to the supply chain.

TSMC’s involvement means Nvidia doesn’t have to sink tens of billions into building its own fabs – an efficient use of capital that can instead go to R&D and other growth initiatives.

However, the risk is that Nvidia is deeply exposed to any disruption in TSMC’s operations or the stability of Taiwan. Geopolitically, Taiwan faces military threats from China, which claims the island, a fact that has raised global concern about the semiconductor supply chain. If, in a worst-case scenario, conflict or blockade were to occur, Nvidia’s ability to get its products manufactured could be severely jeopardized.

Even short of conflict, U.S.-China tensions put pressure on the foundry ecosystem (the U.S. is actively encouraging TSMC to expand in America and imposing rules on what TSMC can produce for Chinese companies). Jensen Huang’s public remarks downplaying the risk should be understood in context; Nvidia likely does not want to signal panic, but the company is certainly aware of the “single point of failure” issue.

To mitigate it, Nvidia has reportedly considered multi-sourcing some chips from Samsung’s foundry in Korea (which it did for a previous generation of GPUs), though Samsung’s tech lags slightly behind TSMC’s.

There is also talk of utilizing Intel’s nascent foundry services in the future. Each of these moves has legal/regulatory angles: e.g., using a U.S. fab might curry favor with American policymakers (especially under the CHIPS Act incentives), whereas any arrangement with Chinese fabs is off the table due to export controls.

Investors should note that Nvidia’s supply chain is international and subject to international law: trade agreements, export licenses for equipment, etc., all affect whether TSMC can keep delivering.

So far, aside from COVID-era hiccups, TSMC has been a reliable partner. But the Taiwan geopolitical wildcard is a lurking risk that could have devastating impact on Nvidia (and its investors) if it ever materialized. Monitoring U.S.-China-Taiwan relations thus becomes indirectly important for an Nvidia shareholder.

ASML and the semiconductor tool chain

ASML is not a direct supplier to Nvidia, but it supplies TSMC with the extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machines needed to fabricate Nvidia’s most advanced chips. ASML, a Dutch company, has a near-monopoly on this critical technology.

The reward for Nvidia is that as long as TSMC can get ASML’s latest machines, Nvidia’s chip designs can be realized in silicon at ever-smaller transistor scales, yielding performance gains that keep it ahead of competitors.

The risk lies in export controls and tech embargoes here as well: the Dutch government, under U.S. pressure, has restricted ASML from selling its most advanced EUV tools to China. While this primarily hurts Chinese chipmakers, a secondary effect is that it heightens the East-West tech decoupling that could, in a future scenario, force companies like Nvidia to pick sides or face supply constraints.

If, for instance, there were sanctions involving Dutch tech, or if ASML had production issues, it could delay TSMC’s roadmap, which in turn delays Nvidia’s. There was also the potential risk (averted for now) that China could retaliate by limiting exports of rare earth metals or industrial materials needed for ASML’s tools or chip production.

For now, Nvidia seems to be managing this well, even collaborating with toolmakers: a recent highlight is Nvidia’s work on computational lithography software (CuLitho) in partnership with ASML and Synopsys to speed up chip production, showing Nvidia is proactively ingraining itself into the semiconductor manufacturing ecosystem.

From a legal standpoint, Nvidia must ensure compliance with any export/import rules around these tools (for example, if it ever brokers installations or provides related software abroad). The main advice to Nvidia investors here is to be mindful that Nvidia’s fate is intertwined with complex export policies affecting its suppliers. A policy change in the Netherlands or a sanctions twist could ripple down to Nvidia’s production schedule.

Arm Ltd. strategic IP licensing

Nvidia’s dependency on Arm is of a different kind. Arm provides the CPU architecture and intellectual property for many chips in the industry. Nvidia itself uses Arm cores in its Tegra mobile/auto chips and in its new Grace CPU (part of the Grace Hopper superchip for data centers).

Nvidia recognized Arm’s importance and attempted to buy the company in 2020-2022, which as discussed was blocked by regulators. The reward of using Arm is that Nvidia can produce powerful integrated systems (combining Nvidia GPUs with Arm-based CPUs, for example) without reinventing the wheel on CPU design.

Arm’s ecosystem is vast, so Nvidia benefits from software compatibility and the innovation of the broader Arm community. The risk here is more subtle: since the Arm acquisition failed, Nvidia must license Arm’s technology just like any other semiconductor firm – and Arm, now preparing for its own IPO, will be an independent entity potentially seeking to maximize licensing revenue. There’s a legal commitment Nvidia made: when the merger was scrapped, Nvidia assured it would remain a friendly partner to Arm and not disadvantage Arm’s other licensees.

But if Arm’s ownership or policies change (imagine Arm being acquired by a consortium of competitors, or Arm significantly hiking license fees), Nvidia could be exposed. The failed merger itself shows a regulatory principle investors should heed: Nvidia may be constrained from acquiring key suppliers due to antitrust concerns, meaning it can’t always fully control its supply chain. It must rely on contracts and partnerships.

Fortunately, Arm has strong incentive to maintain Nvidia as a customer given Nvidia’s influence – and Jensen Huang has praised Arm as central to computing’s future.

Nonetheless, watch for any disputes (industry-wide or Nvidia-specific) in licensing, for instance, Arm recently sued Qualcomm over licensing issues, showing it’s willing to litigate to protect its IP model. If Nvidia ever got into a royalty disagreement with Arm, that could become a legal risk affecting its product plans.

Nvidia’s supply chain dependencies mean that one should keep an eye not just on Nvidia’s own news, but also on news about TSMC, geopolitical developments around Taiwan, export control updates, and Arm’s corporate issues. These external factors can impact Nvidia’s production and product launch timeline.

5. Innovation Pipeline: Blackwell, Rubin, and Next-Gen Chips

Nvidia’s ability to keep investors excited is deeply tied to its product roadmap; the steady drumbeat of new chip architectures and capabilities that drive future growth. The company’s forward-looking announcements, like the upcoming “Blackwell” and “Rubin” GPU architectures, showcase an aggressive innovation pipeline that can translate into big rewards. However, pushing the envelope on chip technology also comes with legal and regulatory considerations, from export limits on ultra-powerful chips to intellectual property challenges and execution risks.

Nvidia has a history of leapfrogging itself with each generation of GPUs (named after scientists: previous gens include Tesla, Fermi, Kepler, Maxwell, Pascal, Volta, Turing, Ampere, and the current flagship for data centre, Hopper). The next in line for data center AI is Blackwell.

Blackwell-based systems are expected to underpin trillion-parameter AI models and have already been unveiled in Nvidia’s latest supercomputer offerings. In fact, Nvidia is launching Blackwell-powered products like the DGX SuperPOD AI supercomputer to enable a new era of generative AI at massive scale.

Each new architecture typically spurs an upgrade cycle: cloud providers and enterprises will spend to replace older GPUs with the newest for better performance per dollar. That can mean surging revenue in the years a major product is introduced. Blackwell, rumoured to use advanced multi-die designs, promises significant performance gains. Looking further out, Nvidia has already teased the “Rubin” architecture, expected around 2025–2026 (named after astronomer Vera Rubin), which will succeed Blackwell.

Early reports suggest Rubin could triple certain AI performance metrics over Blackwell by using even more advanced packaging and memory technology. Nvidia has even mentioned a successor beyond Rubin named “Feynman” (targeted for 2027+). The clear message: Nvidia has a roadmap to continue doubling or tripling AI chip capabilities every couple of years, which is a tremendous tailwind for investors banking on the AI revolution’s expansion.

A robust pipeline also helps Nvidia maintain its competitive moat – while rivals (AMD, startups, etc.) are aiming at Nvidia’s lead, Nvidia’s head start and continuous R&D investment keep it ahead of the pack, which in turn helps sustain its market share and pricing power.

Interestingly, as Nvidia’s chips become more powerful, they aren’t just engineering marvels; they are also potential subjects of regulation themselves. The U.S. export controls we discussed above actually define performance thresholds (in terms of chip speed, interconnect bandwidth, etc.) above which chips cannot be freely sold to certain countries. When Nvidia develops Blackwell or Rubin, it must do so with an eye on these rules. In late 2023, for example, the U.S. tightened export rules to ensure that even modified chips (A800, H800) could not slip through.

Going forward, if Blackwell offers a big leap, Nvidia might have to produce a special downgraded variant for export-restricted markets, or accept that those markets are off-limits. Regulators could further lower the performance cutoff as AI chips advance, effectively putting a legal ceiling on the top capabilities Nvidia can sell overseas. This dynamic means Nvidia’s very innovation could outpace what governments are comfortable allowing to spread globally, entwining product roadmap with policy.

In the U.S., there’s also a national security consideration: extremely powerful AI chips might be seen as strategic assets (much like supercomputers are), possibly invoking government oversight on who can purchase them even within allied countries. While we are not there yet, investors should note that Nvidia’s most advanced products might increasingly be influenced by government licensing and oversight.

Another risk area is intellectual property and patent law as it relates to new architectures. Nvidia’s rapid development pushes into new technical territory, which sometimes overlaps with patents held by others or prompts others to challenge Nvidia’s patents.

For instance, when Nvidia moves to multi-die GPUs (chiplets) or new memory architectures, it must be careful not to infringe on existing IP. Competitors and smaller patent holders are keen to assert claims if they believe Nvidia’s lucrative chips use their inventions.

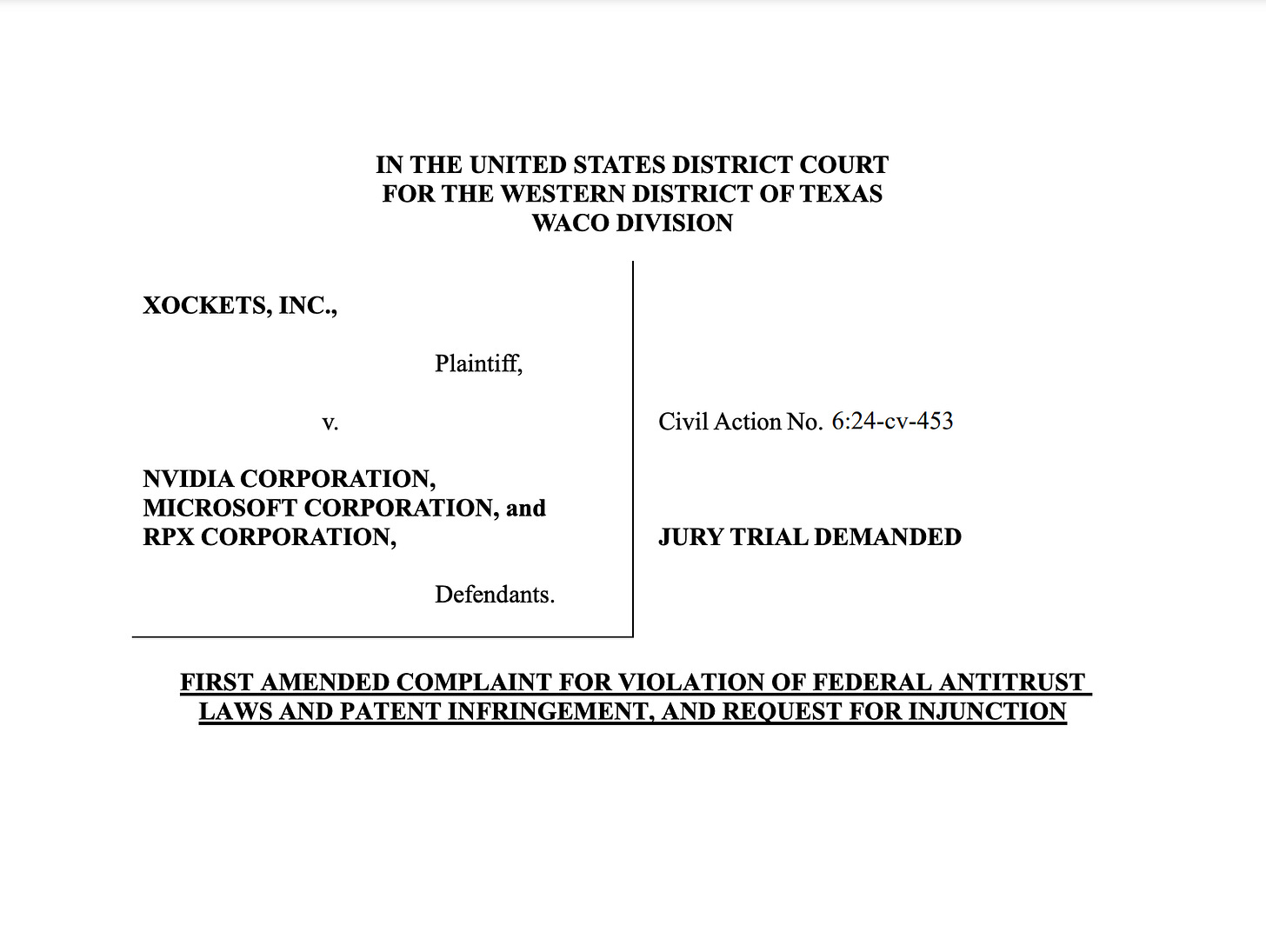

A recent example: a small company named Xockets sued Nvidia in 2024, claiming Nvidia’s newest data processing units (DPUs) and even its forthcoming Blackwell-based systems use Xockets’ patented technology without permission.

That lawsuit also roped in Nvidia’s partner Microsoft, alleging an antitrust conspiracy to suppress Xockets’ innovations. While such cases can be speculative, they highlight how Nvidia’s big moves attract legal attacks. Most often these get settled or dismissed, but a significant patent loss could, in theory, result in royalties owed or an injunction (Xockets audaciously sought to block the sale of Blackwell GPUs, for example).

Nvidia vigorously defends its IP, and also has a huge war chest of its own patents to counter-sue if needed, so the company has managed to avoid any devastating IP judgments so far. Nonetheless, with Rubin and beyond likely introducing radical designs (maybe new interconnects, 3D chip stacking, etc.), Nvidia will need to manage the patent quagmire and possibly license technologies or cross-license with others.

Investors generally don’t need to panic about every lawsuit (they are somewhat routine in tech), but should be aware that IP challenges are part of Nvidia’s innovation story. A protracted legal battle could slightly delay a product or cost some settlement money, factors to keep in mind when valuing the asset.

Additionally, product reliability and compliance are areas to watch. As chips become more complex (hundreds of billions of transistors, new cooling requirements, etc.), Nvidia must comply with safety and environmental regulations. For example, high-powered data centre GPUs draw lots of electricity, so they must meet electrical and thermal safety standards across various countries.

If a new product had an issue (say a manufacturing defect causing failures), it could prompt recalls or liability claims. So far, Nvidia’s track record here is good, but scaling up chip complexity always bears some execution risk that could have legal ramifications (warranty claims, etc.).

6. Partnerships with Tech Giants

Nvidia does not operate in a vacuum; it has woven itself into the strategies of virtually every major tech titan pursuing AI. Partnerships with companies like Microsoft, Meta (Facebook), Google, Amazon, and others amplify Nvidia’s reach and offer substantial rewards.

These alliances can secure huge orders for Nvidia’s products and integrate Nvidia’s platforms deeper into industry workflows. However, close partnerships also bring legal considerations: from competition law (if collaborations are seen as too exclusive) to dependency risks and contractual obligations that investors should understand.

When Microsoft wants to build a world-class AI supercomputer for services like ChatGPT, it turns to Nvidia.

In fact, Microsoft and Nvidia have a deep collaboration, for example, Microsoft Azure is hosting Nvidia’s DGX Cloud, essentially renting out Nvidia’s advanced AI infrastructure as a service.

The two companies have also partnered to connect Nvidia’s Omniverse (a 3D metaverse and simulation platform) with Microsoft’s industrial cloud apps.

For Nvidia, such partnerships mean direct revenue (Azure buying loads of Nvidia H100 GPUs to power these services) and strategic validation (being the chosen provider for a fellow tech giant).

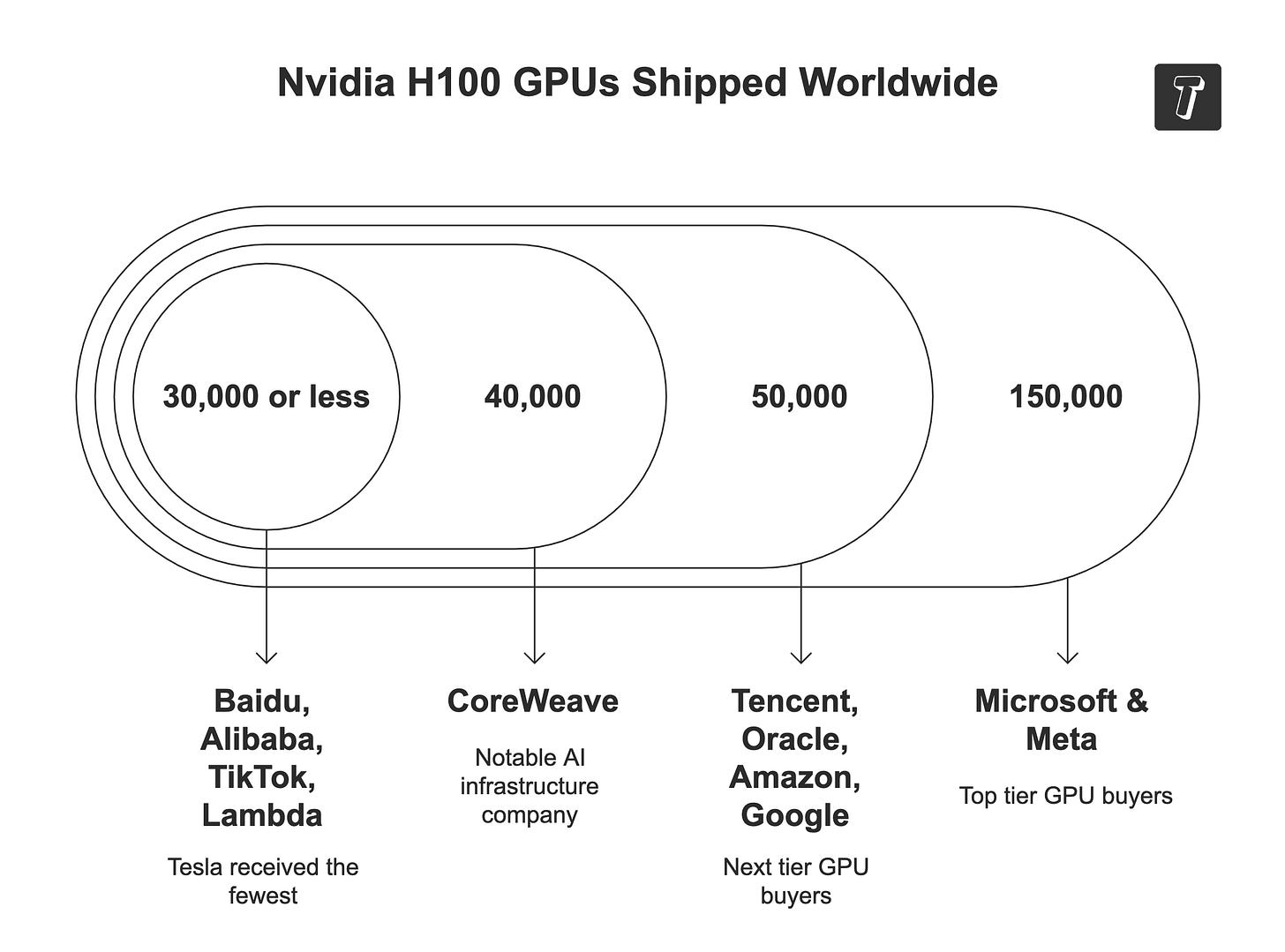

Similarly, Meta (Facebook) has been a massive Nvidia customer. Meta’s AI research and its open-source large language models (Llama) are built on Nvidia hardware. Meta has publicly shared plans to equip its data centers with astonishing numbers of Nvidia GPUs – aiming for 350,000 Nvidia H100 GPUs by end of 2024 and potentially over a million Nvidia AI chips in the longer term as it invests $60–$70+ billion in AI infrastructure. These are essentially multi-year sales locked in for Nvidia, providing a robust demand floor.

Google uses Nvidia GPUs in its cloud (even as it develops its own TPUs, it still offers Nvidia instances for customers who prefer them), Amazon AWS likewise offers Nvidia-based GPU cloud services, and Oracle reportedly placed a huge order (some sources say ~$40 billion) for Nvidia chips to support OpenAI’s needs.

Beyond cloud, Nvidia partners with carmakers like Mercedes, Toyota, and others for its autonomous driving platforms, and with a host of enterprise software firms (e.g., SAP, VMware) to optimize AI workflows on Nvidia hardware. Each partnership expands Nvidia’s market and often co-markets its tech to new customers.

These alliances are reassuring because since Microsoft and Meta builds around Nvidia, they are unlikely to switch out in the short term. It also suggests Nvidia can share some R&D burdens or market development with these partners. For instance, if Nvidia is working closely with Microsoft on AI safety or compliance in the cloud, that could help pre-empt regulatory issues for both. Additionally, partnerships can open new revenue streams: e.g., Nvidia might get service subscription income from its software (like AI Enterprise or Omniverse) through cloud providers in addition to just selling chips.

While partnerships are positive, there are a few angles to watch. One is antitrust/competition law, ironically, being too cozy with certain partners could draw scrutiny if it’s seen as collusive or exclusionary. For example, if Nvidia and Microsoft have an arrangement that somehow disadvantages Microsoft’s cloud competitors, regulators could ask questions. At the extreme, consider if Microsoft got preferential pricing or supply of Nvidia GPUs and others couldn’t get enough, that might raise fairness issues in cloud competition.

There’s no open case on this now, but the EU’s broad inquiry into Nvidia’s practices does include asking customers if they felt pressured in any deals – presumably partners like Microsoft/Meta are large enough to negotiate freely, but smaller customers might worry that Nvidia prioritizes the big allies.

Collaboration vs. collusion is a fine line legally; in the Xockets lawsuit mentioned earlier, the startup alleged Nvidia and Microsoft conspired via a patent risk aggregator (RPX) to lower what they’d pay for certain IP. Nvidia and Microsoft will surely fight that claim, but it shows how partnerships can entangle Nvidia in legal battles beyond its direct making.

If Nvidia relies on a handful of big buyers for a large chunk of its sales, any rift or change in those relationships could impact its financials. For instance, Meta recently has explored developing some of its own AI chip solutions, though it continues to buy from Nvidia in the interim. If someday a key partner like Meta or Amazon successfully builds an in-house alternative and reduces orders from Nvidia, that’s both a business risk and possibly an IP risk since often those efforts involve ex-Nvidia engineers or similar designs, potentially leading to IP disputes.

So far Nvidia’s tech is ahead enough that partners are mostly augmenting rather than replacing Google’s TPUs co-exist with Nvidia GPUs for flexibility; Amazon’s Trainium chips are used alongside Nvidia’s for different tasks. But as an investor, one should watch announcements from these partners, if, say, Microsoft or Meta were to make a major acquisition of a chip startup or debut a breakthrough AI chip, it might signal a pivot away from Nvidia.

Legally, Nvidia might respond by enforcing any contractual long-term commitments those partners have made or by asserting IP rights if any proprietary tech is at issue. In the past, Nvidia has not shied from suing to protect its turf, it once sued Samsung over GPU patents years ago.

One could foresee Nvidia enforcing its CUDA software lock-in; since many partners’ AI code is written for CUDA, switching to another GPU means rewriting a lot of software, which is a non-legal but very real barrier.

Big enterprise partnerships come with detailed contracts that can have both upside and downside. Some might include volume commitments, ensuring a steady flow of orders, but also penalty clauses if either party fails to deliver.

For example, if Nvidia had a contract to deliver X number of GPUs to a cloud partner by a deadline and supply chain issues delayed that, Nvidia could face financial penalties or have to prioritize that partner at the expense of other customers. These are not usually public, but investors saw a glimpse during the pandemic when some chip companies had to pay fines for missing supply deadlines.

Also, working closely with giants like Microsoft means Nvidia must adhere to those companies’ strict compliance standards, re: data handling, security, etc. Should an issue arise, imagine a security flaw in Nvidia’s hardware that jeopardizes a cloud service, it could lead to liability or indemnification debates under the partnership agreements.

7. Compliance, Transparency, and Ethical Governance

A company like Nvidia must ensure its corporate governance, compliance, and ethical practices are sound, or risk undermining investor confidence and inviting legal trouble. In the past, Nvidia has faced some compliance missteps, albeit relatively minor in scale, and going forward, the expanding scope of its business (especially in AI) introduces new areas where ethical and regulatory compliance is paramount. For retail investors, a well-run, transparent company is less likely to get hit by nasty surprises such as fines, restatements, or scandals that could damage the stock.

Financial and disclosure compliance

One notable incident occurred in 2018: Nvidia experienced a surge in sales of GPUs due to cryptocurrency miners buying up gaming graphics cards. However, the company did not fully disclose to investors the extent to which crypto-mining was driving its revenue in its gaming segment. This came to a head when, in 2022, the U.S. SEC charged Nvidia for inadequate disclosures – essentially saying Nvidia misled investors by not quantifying how much crypto demand was boosting gaming sales, which was a material factor especially when crypto volatility later hit sales.

Nvidia agreed to settle and paid a $5.5 million fine to the SEC. While $5.5M is pocket change for a company of Nvidia’s size, the episode was a wake-up call on transparency. The reward of compliance is trust and stability; the risk of non-compliance is reputational harm and legal penalties. Since then, Nvidia appears to have improved its segment reporting and risk disclosures.

For example, when AI demand boomed, Nvidia explicitly broke out data centre revenues and even mentioned factors like cryptocurrency impacts, positive or negative, in commentary. This means Nvidia’s financial statements are likely more straightforward now, a good sign that we can rely on reported segment performance without hidden drivers.

Regulatory compliance in operations

Nvidia must comply with a web of regulations: export controls (discussed), environmental and safety regulations in manufacturing (its contractors’ factories must meet standards, and Nvidia as a product maker has to ensure things like RoHS compliance, i.e., no hazardous substances in chips), and employment and anti-corruption laws wherever it operates.

Nvidia operates in many countries and thus falls under the U.S. FCPA anti-bribery law, among others. There have not been public issues with Nvidia on those fronts, which suggests a strong internal compliance program. Any lapse e.g., an employee caught paying bribes to secure a deal in some country could lead to investigations or fines, but Nvidia has not had such scandals.

As it becomes more involved in government contracts and sensitive sectors like defence AI or healthcare AI, compliance burdens increase, for instance, adhering to data privacy HIPAA for health if its tech is used in medical imaging, or defence acquisition rules if supplying to DoD projects.

Nvidia has to maintain strict data security, imagine if customer data from an Nvidia cloud AI service leaked, it could cause lawsuits or regulatory fines especially under EU’s GDPR or similar laws.

Ethical use of AI and corporate responsibility

A growing area is AI ethics and compliance. Nvidia mostly sells the tools (chips/software) rather than deploying AI services itself, but it has some cloud and software offerings like NVIDIA AI Enterprise, and partnerships where it hosts models.

With AI under scrutiny for bias, misuse, or generating harmful content, Nvidia has an interest in ensuring its technology is used responsibly. We haven’t seen Nvidia at the center of any AI ethics storm, those tend to hit the application providers like OpenAI or Clearview AI.

However, Nvidia did face a small controversy in 2020 when its AI research team created “fake people” portraits, this was more of a cool demo but sparked discussion on deepfakes, not a legal issue for Nvidia, but indicative of the dialogues around AI tech.

As governments mull regulations specifically on AI like the EU AI Act which could require transparency about AI-generated content, or U.S. considerations to mandate reporting of large AI training runs, Nvidia might have to build in compliance features.

For example, if there were a law that “AI models above X size must register or include watermarks in their output,” Nvidia as a supplier might be asked to incorporate watermarking tools at the hardware or software level for customers.

Complying with any such future AI laws will be important to avoid legal liability. Nvidia has shown some leadership here, e.g., developing watermarking for images from its StyleGAN generator. Investors should be aware that regulatory shifts in AI like labeling requirements, export of AI models, etc., could impose new costs or limitations on Nvidia’s offerings – albeit equally on its competitors. Nvidia’s proactive engagement is a good sign it will adapt.

Corporate governance and ESG

From an investment perspective, Nvidia’s governance appears strong. The company has an independent board, and Jensen Huang, as both CEO and a major shareholder, generally aligns with shareholder interests (his large ownership stake incentivizes him to increase long-term value).

There have not been governance scandals. On ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) metrics, Nvidia scores decently but not perfectly, the main knocks might be environmental, chip manufacturing has a carbon footprint, though Nvidia itself isn’t a fab operator, and social workforce diversity in tech is an industry-wide challenge.

One could argue these aren’t immediate legal issues, but they tie into long-term risk. For instance, if Nvidia is perceived as not addressing the environmental impact of AI as a result of huge electricity usage in GPU clusters, regulators could impose efficiency standards that affect product design.

Nvidia actually often highlights how GPUs save energy overall by doing more work per watt than CPUs for AI tasks, effectively framing itself as part of the climate solution for computing. This positioning is smart to pre-empt potential regulatory pressure on “AI power hogs.”

8. Diversification into New Sectors: New Opportunities, New Regulations

Nvidia’s core success has come from graphics and AI processors, but the company has ambitiously expanded into new markets such as automotive driving systems, robotics, healthcare, and the so-called “omniverse”, 3D simulation and virtual world platforms.

Each new sector offers attractive growth prospects, a reward for investors through the opening of additional revenue streams.

Automotive (self-driving and ADAS systems)

Nvidia’s DRIVE platform, which includes hardware like the DRIVE Orin and upcoming DRIVE Thor chips, and software stacks for autonomous driving, has positioned the company as a key player in the race toward self-driving cars.

The automotive industry is huge, and as vehicles become computers-on-wheels, the silicon content (and value) per vehicle can increase greatly, with Nvidia capturing a slice of that.

Nvidia has already secured partnerships or design-wins with major carmakers like Mercedes-Benz, Volvo, Audi, and China’s NIO, as well as with newer EV makers and robotaxi firms. It recently announced that Chinese EV companies like BYD and XPeng have chosen Nvidia’s next-gen DRIVE Thor platform for their future models.

This indicates a strong pipeline of automotive revenue in coming years; Nvidia’s automotive revenue was $0.3B last quarter, relatively small, but the order pipeline is much larger. If full self-driving cars become mainstream, Nvidia stands to gain significantly.

The legal risk in automotive is that this is a highly regulated industry with safety at its core. Automotive electronics must meet strict functional safety standards such as ISO 26262. If Nvidia’s hardware or software were to contribute to a failure in a car that causes injury, Nvidia could be exposed to product liability claims. Typically, the automaker would be on the front line of liability, but they might in turn press suppliers. Nvidia must ensure its systems are certified and validated to automotive-grade reliability. It has been investing in that, but it’s a different bar than consumer electronics.

There is also the regulatory uncertainty around autonomous driving, governments might require certain certifications or even infrastructure for self-driving cars. Nvidia can influence but not control that timeline. For example, if regulators slow the approval of robo-taxis due to safety concerns, Nvidia’s automotive ramp could be slower, which is a business risk, not legal liability per se, but regulatory pace affecting market adoption.

Data privacy and mapping

Self-driving systems collect massive sensor data (cameras, LiDAR). In some jurisdictions, how that data is used or shared is regulated. Nvidia’s platforms, if they upload data for cloud training, must ensure compliance with privacy laws e.g., faces or license plates captured in video might be considered personal data under GDPR in Europe.

This is a nascent issue, but as an investor it’s good to be aware that Nvidia’s role in handling automotive data could draw it into privacy or cybersecurity regulations, cars are increasingly under cybersecurity rules to prevent hacking, Nvidia’s systems need to be robust against that; a hacked Nvidia automotive chip could be a nightmare scenario, so they likely invest heavily in security features.

Robotics and Edge AI

Nvidia has been pushing Jetson, its small AI computers, for robots, drones, and industrial applications, and more recently its IGX platform for things like medical devices. The rewards are diversification into many verticals – from manufacturing automation to retail analytics, AI-powered checkout systems, etc.

Each of these has its regulatory angle: for instance, a medical device that uses Nvidia tech to do AI diagnostics would need FDA approval. Nvidia itself might not seek the approval, the device maker would, but Nvidia would need to provide support and documentation about how its hardware/software performs, so-called “Software of Unknown Provenance” issues.

If a robot powered by Nvidia AI malfunctions and hurts someone, again product liability law comes in, the maker of the robot is first in line, but if Nvidia’s component is proven defective, it could share liability. To manage this, Nvidia likely has strong warranties and limits of liability in its contracts.

The key is that these sectors often have longer sales cycles and heavy regulation, meaning revenue might not explode overnight, but once designed in, it can be sticky. Also, regulators might impose requirements like explainability of AI decisions, if Nvidia provides an AI platform for, say, a hospital, it might need to incorporate features that allow audits of the AI’s decisions for legal compliance.

Omniverse and Virtual Worlds

Nvidia’s Omniverse platform is an ambitious bid to enable collaboration in simulated 3D worlds, for design, engineering, even digital twins of factories or cities. The opportunity is that this could become like an “Adobe of 3D” or the backbone of the industrial metaverse, with Nvidia hardware powering it and subscription software revenue. Legal aspects here include intellectual property of content if Omniverse is used to create assets, who owns them? Likely the user, but Nvidia has to ensure its platform doesn’t accidentally infringe on other software IP.

Also, any cloud-based service means Nvidia has to deal with terms of service, possible content moderation if Omniverse is ever used socially, though currently it’s enterprise-focused. For now, Omniverse is more a B2B tool, so less of a minefield than consumer social platforms. But if Nvidia ever expanded it to consumer metaverse applications, it would have to consider things like unlawful content creation, etc.

One tangential risk: antitrust; Omniverse combines with Nvidia’s core hardware; competitors might worry Nvidia will favor itself, indeed, there’s some chatter that using Omniverse on Nvidia GPUs gives performance benefits. If Omniverse became essential, that vertical integration could be scrutinized.

Cryptocurrency and FinTech

Though not mentioned in the prompt explicitly, a brief note: Nvidia’s cards have been used for crypto mining. Crypto is a legally gray area in some jurisdictions.

Nvidia already got in trouble for disclosure around crypto. They also implemented technical limits to discourage miners on some GPUs which led to hacking and interestingly, hackers retaliating by leaking some data from Nvidia as noted before.

Now with Ethereum moving away from GPU mining, that issue has receded. But if a new crypto or similar pops up that relies on Nvidia GPUs, Nvidia might again face a balancing act: enjoy the sales but manage the impact. Also, money laundering concerns, theoretically, someone could buy a huge batch of GPUs to launder money via crypto mining.

Unlikely scenario, but Nvidia’s sales of high-value tech might be subject to export and anti-money-laundering scrutiny if going to certain regions or via sketchy intermediaries. It’s another compliance area, albeit low risk for a hardware vendor.

Investor Takeaway

Nvidia’s story is one of unparalleled growth in the AI era, intertwined with a complex web of legal and regulatory dynamics. For investors, the rewards of Nvidia’s rise are clear: soaring revenues in data centres, leadership in the critical hardware enabling AI breakthroughs, and expansion into new arenas from autonomous vehicles to cloud services.

The company’s alliances with giants like Microsoft and Meta further cement its role in the tech ecosystem, promising continued demand. In short, Nvidia is “powering the AI revolution,” and investors have reaped the benefits in stock performance.

Yet alongside these opportunities, Nvidia faces a spectrum of legal risks that prudent investors should keep in mind. Export controls restrict access to big markets with ongoing U.S.-China tensions requiring constant compliance agility.

Antitrust scrutiny is mounting as Nvidia’s market dominance grows, regulators globally are asking whether Nvidia’s business practices need reining in, which could foreshadow investigations or rules to ensure competition. Critical supply chain dependencies mean geopolitical events could impact Nvidia more than most e.g., any disruption in Taiwan or in the flow of high-end chip equipment. The company’s relentless innovation must be balanced against patent rights and possible IP challenges, as seen by occasional lawsuits, though Nvidia’s strong IP portfolio largely protects it.

Meanwhile, stepping into sectors like automotive and healthcare brings new regulations (safety, privacy) that Nvidia must adhere to, and the company’s past brush with disclosure issues highlights the need for transparent governance, a lesson Nvidia appears to have learned.

The overarching strategy is diversification and due diligence. Nvidia remains a compelling investment, it’s at the nexus of multiple tech megatrends, but it is not without risks that stem from factors beyond pure market demand.

In conclusion, Nvidia offers a case study in high-reward innovation balanced by multidimensional legal risk. Thus far, the company has demonstrated deft handling of these challenges, turning many into mere speed bumps rather than roadblocks.

The themes we explored show that an investor in Nvidia must wear two hats: that of a tech believer excited about the growth, and that of a risk manager mindful of laws and geopolitics. The good news is, Nvidia’s management appears to be wearing both hats too, driving the company forward while keeping an eye on the rearview mirror for regulators and compliance obligations.

For investors with a suitable risk appetite, Nvidia remains an attractive vehicle to ride the AI revolution.

Nvidia does not make its own chips; it designs them. TSMC is among the primary manufacturers of Nvidia chips. That partnership has worked beautifully so far, but it also ties Nvidia’s future to global politics. Any disruption in Taiwan (or tension between the U.S. and China) could ripple straight into Nvidia’s supply chain. Jensen Huang says he feels “perfectly safe” relying on Taiwan. Investors watching Nvidia might want to keep an eye on what is happening far beyond Silicon Valley, geopolitical headlines really do matter here.

In 2022, Nvidia paid a $5.5 million settlement after the SEC said it was unclear how much crypto mining was driving its gaming chip sales. The SEC's oversight demonstrated just how closely watched Nvidia is. Since then, the company’s disclosures have become more upright, especially around AI revenue. The AI economy is exploding. Therefore, it is not unusual for regulators, markets, and media to scrutinize Nvidia's activities.