How a Simple WhatsApp Message Led to a Six-Figure Contract Dispute (Jaevee Homes v. Fincham)

Newsletter Issue 34 (Case Report): The High Court just confirmed that a one word WhatsApp message can form a binding business contract.

Most people use WhatsApp daily to confirm plans, send updates, or sort quick decisions with tradespersons. But in a recent court case, a few short messages on WhatsApp turned into something much bigger; a legally binding contract worth nearly £250,000. By the way, there were no signatures and no paperwork. Just casual texts via WhatsApp. This newsletter breaks down how it happened, why the court upheld the messages as a valid agreement, and what that means for anyone doing business through messaging apps.

🏛️ Court: High Court of Justice (Business and Property Courts of England & Wales, Technology and Construction Court)

🗓️ Judgment Date: 16 April 2025

🗂️ Case Number: [2025] EWHC 942 (TCC)

Can A Valid Contract Be Formed via an Informal WhatsApp Chat? 👍

The case considered on whether a legally binding construction contract was formed via a WhatsApp exchange between a property developer and a demolition contractor.

The parties exchanged several messages discussing price, timing, and payment structure. On 17 May 2023, the developer confirmed the job over WhatsApp and mentioned that monthly payment applications would be expected. The contractor replied with a clarification about receiving payments every 28 to 30 days from invoice.

The developer responded with "Ok" and said they would “chat in the morning.”

The key legal question was:

Did that casual WhatsApp conversation, which confirmed acceptance and touched on payment expectations, amount to a legally enforceable construction contract?

This issue mattered because if the messages created a contract, then that agreement would govern when and how payments should be made, especially relevant when disputes later arose about unpaid invoices. If not, then a later, formal subcontract (sent via email with more detailed terms) would apply instead.

⚖️ The case explored:

Whether modern text messaging apps like WhatsApp can form contracts in construction law.

Whether basic terms like price and timing, discussed informally, can override later formal documents.

Whether referencing "monthly applications" in messages limits the contractor to only one invoice per month.

If no detailed payment terms were agreed, whether default statutory rules under UK construction law would apply instead.

Essentially, the court had to decide how far informal WhatsApp messages can go in forming legally binding agreements in commercial construction projects.

This case is important for us because it clarifies that common messaging platforms may carry legal weight, even in high-value business deals, and businesses need to be careful about what they say and agree to through these social media channels.

What Led To The Dispute?

In early 2023, Jaevee Homes Ltd, a property developer, sought demolition services for a former nightclub in Norwich known as the Mercy site. They contacted Steve Fincham, trading as Fincham Demolition, to provide a quote for the works.

On 11 May 2023, Fincham issued a formal written quotation totalling £256,000 + VAT for a four-part demolition job. This included scaffolding, staircase removal, wall demolition, and other structural takedowns.

From 12 May 2023, communications between Jaevee and Fincham moved to WhatsApp, with pricing negotiations and timing discussions taking place in a casual format. On 17 May 2023, a WhatsApp conversation occurred:

📲 Fincham asked whether the job was his.

📲 Ben James (CEO of Jaevee) asked if Fincham could start on Monday.

📲 Fincham confirmed he could begin preparations and scaffolding that day, with workers starting the following Monday.

📲 Fincham asked again if the job was his.

📲 James replied: "Yes".

📲 James then added: "Monthly applications".

📲 Fincham replied, asking if this meant every 28 or 30 days from invoice and confirmed he did not want a "draw down" model (where payments depend on client funds).

📲 James responded: "Ok" and "Chat in the am".

📲 Fincham replied: "Thanks Ben" 🙏

Fincham interpreted this as a “go ahead” to begin organizing work and invoicing accordingly.

On 24 May 2023, scaffolders began adjusting structures onsite.

By 30 May 2023, Fincham had mobilized his own team and started demolition.

On 26 May 2023, Jaevee sent a formal contract and documentation via email, including a Subcontract with structured terms for payment and invoicing.

However, Fincham never replied to this email nor explicitly agreed to the new documents.

In the following weeks, Fincham issued multiple invoices:

Invoice 1078: £48,000 + VAT, issued 9 June 2023 🧾

Invoice 1079: £100,000 + VAT, issued 23 June 2023

Invoice 1081: £38,750 + VAT, issued 14 July 2023

Invoice 1083: £9,107.50 + VAT, issued 27 July 2023

Jaevee made partial payments totalling £80,000, but disputed the validity of the invoices and the number submitted, referencing their own subcontract terms which expected just one invoice per month.

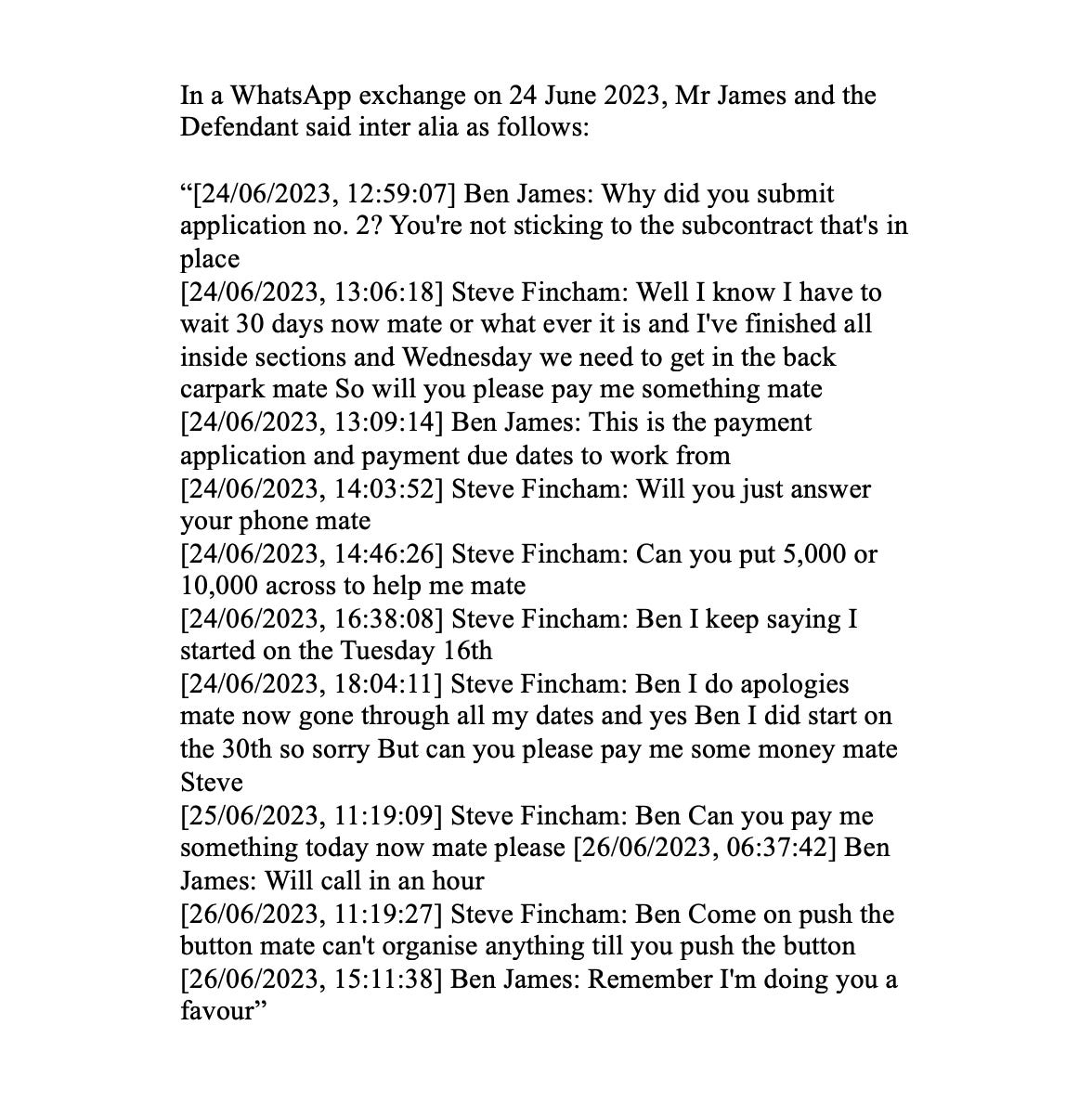

On 24 June 2023, more WhatsApp messages show increasing tension:

Jaevee asked why a second invoice had been submitted so soon.

Fincham explained he had completed substantial work and needed funds urgently.

James insisted payment timing must follow their terms.

Fincham repeatedly asked for partial payments to cover ongoing expenses 💸

Disputes escalated. Jaevee claimed the official contract sent on 26 May was binding. Fincham maintained that the 17 May WhatsApp conversation was the true contract formation point, especially as he had already begun work and received no rejection of that interpretation.

The case ultimately centred on which communication formed the contract.

It can be argued that the WhatsApp messages played a key role in establishing expectations, timing, and obligations between both parties.

Final Judgment by the High Court 🏛️

The High Court ruled that a legally binding contract was formed between Jaevee Homes and Steve Fincham through their WhatsApp exchange on 17 May 2023.

📌 The Judge found that:

The parties had agreed to start the demolition project.

A fixed price of £248,000 + VAT had been accepted.

Payment terms were agreed: Fincham could send one invoice per month, to be paid within 28 to 30 days.

🗓️ The court concluded that:

The agreement on WhatsApp was complete and binding.

Later formal contract documents sent by Jaevee on 26 May 2023 were not part of the agreement because they were not acknowledged or accepted by Fincham.

The WhatsApp messages reflected the intention to proceed and confirmed the deal, despite being informal.

⚖️ The Judge declared:

Fincham had the right to send one invoice per month.

Payment was due 28 to 30 days after invoice submission.

Jaevee’s attempt to impose its own standard contract terms afterward was not valid.

💷 The court also dealt with prior enforcement proceedings. It upheld an earlier adjudicator’s ruling requiring Jaevee to pay £137,472.12, after deducting a prior cost order, plus legal fees of £22,971.20.

🎯 This case serves as a reminder that short digital messages via social media platforms can carry real legal consequences in business, especially where work has started and payment terms are clear.

Key Lessons When Contracting on Social Media

This case provides important legal insights for professionals, especially those working in construction, property development, or any business that uses messaging platforms like WhatsApp for deal-making.

The ruling from the High Court reinforces several core legal principles that can apply across industries when using informal social media communication channels.

1. Informal Messaging Can Create Binding Contracts 💬📝

One of the clearest lessons is that a legally binding contract can be created through casual digital communication such as WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, etc.

If the essential elements of a contract are present, the format/platform does not matter.

A valid contract under common law typically requires:

An offer

Acceptance

An intention to create legal relations

Consideration (usually money or value exchanged)

📱 If these elements are present in a WhatsApp message thread, the court may treat it as a binding agreement, even if no formal document was signed.

This means that informal language, emojis, and brief replies like "Yes" or "Ok" can contribute to the formation of a contract if they clearly indicate agreement and intent.

2. Parties Do Not Always Need a Formal Document 📁✍️

The judgment confirms that a written contract, such as a PDF or printed agreement, is not always necessary to create enforceable obligations. What matters is whether the parties intended to be legally bound by what was said.

💡 Lesson:

If one party confirms the job, agrees on the price, and the other party begins performance, the law may treat that as sufficient for a contract.

This principle encourages businesses to treat all communications carefully. Assumptions that a formal agreement will follow later may not protect a party who has already agreed key terms informally.

3. Clear Terms Matter, Even in Chats 🔍📆

The case highlights that even when using chat apps, the terms agreed must be understandable and consistent.

Some examples of key terms that matter:

Agreed price

Description of services or goods

Payment terms (how often, how much, when due)

Timelines or start dates

In this case, the parties used language like "monthly applications" and discussed payment cycles (e.g., every 28 to 30 days). The court interpreted that as a clear term regarding how many payment applications could be submitted.

📌 Tip:

Messages that leave room for different interpretations can lead to disputes. It is helpful to follow up with confirmation of what both parties meant.

4. Later Formal Documents May Not Override an Earlier Agreement 📤🧷

If a contract has already been formed through messaging, sending a formal document later does not change the original agreement unless both parties accept it.

This is especially important in industries where it is common to send detailed subcontracts after work begins.

💼 The court in this case found that documents emailed several days after the WhatsApp conversation were not part of the contract because they were not acknowledged, accepted, or signed by the other party.

📌 Takeaway:

Sending terms after work has begun will not always override the deal already made, unless the other party clearly accepts those new terms.

5. Courts Look at Conduct as Well as Words 🧑⚖️

The behaviour of both parties after the messages were exchanged helped the court understand what had been agreed.

This includes:

Whether work began shortly after

Whether invoices were issued

Whether payments were made

Whether there was any objection to the arrangements

👍 The court considered this real-world conduct as evidence of agreement.

This reinforces that courts will not only look at documents and messages but also at what people did in practice to determine the existence and content of a contract.

6. Contract Terms Can Be Simple and Still Be Binding 💡

Even if a contract does not include all the fine print that lawyers often insert, it can still be enforceable. The law allows simple agreements as long as they include the key terms and both parties act on them.

🧠 Importantly, where terms are missing or unclear, the law may "fill in the gaps" using standard statutory rules. For construction contracts in England, this often means applying the rules under the Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 and the Scheme for Construction Contracts.

📌 Practical Lesson:

Do not assume that a contract must be complicated to be valid. The simpler your message exchange, the more important it is to be precise.