If Your AI Tool Tries to Read Feelings, You Need to Take Action Immediately

Newsletter Issue 8 (Law Reform): Dutch regulators are questioning emotion AI and its impact on society. Could this spell the end for mood-detecting tech?

The Dutch privacy regulators just closed a public consultation on emotion-detecting AI. From creepy job interviews to mood-reading cameras, this AI tech is under serious fire. If your AI-based product touches emotions, even a little, you will want to see what’s brewing in the Netherlands.

🇳🇱 Netherlands Shuts the Door (For Now) on Emotion AI: What It Means for Tech Founders and Product Teams

If you are building with AI, or even just watching from the sidelines, then this one’s worth a close look. The Netherlands’ Data Protection Authority (Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens or AP) has just closed a public consultation on the use of “emotion AI” in society. And the message was clear: proceed with caution, if at all.

This regulation is tackling the rising trend of companies scanning faces, voices, and behavioural patterns to guess how someone feels, and regulators drawing a clear red line around it.

So let’s dig into what’s actually happened, why the Dutch are doing this now, and what it signals for anyone working in AI or using it to build customer experiences, marketing tools, or workplace products.

First, What Is Emotion AI, and Why Is It So Controversial?

Emotion AI is a branch of artificial intelligence that claims to read and interpret human emotions. Think facial recognition tech that says, This person looks frustrated, or a job interview system that flags candidates as too nervous. Some tools use tone of voice, eye movement, or even heart rate data.

Sounds futuristic? It’s already here. Companies are embedding emotion AI into customer service bots, hiring software, education platforms, and even smart city surveillance.

But here’s the issue: emotions are messy, culturally nuanced, and deeply personal. Trying to predict them with code, especially at scale, risks a lot more than just bad UX. It raises serious privacy and discrimination concerns, especially under strict European data laws like the GDPR.

What the Dutch Data Protection Authority Did

In March 2024, the AP launched a consultation asking the public: “What’s your experience with emotion AI?” Not just from a technical angle, but from a societal one. They invited people to describe real-life encounters with emotion-recognition technology. The regulator wanted to know:

Where are people encountering these tools?

How are they being used by companies, government bodies, or schools?

What concerns do people have?

Fast forward to this month, and that consultation is now officially closed. The AP will now analyse responses as part of its broader “AI and Algorithmic Risks” report. This is not just academic. It’s groundwork that could shape how emotion AI is treated under Dutch law and perhaps influence wider EU policy.

The consultation came after the AP’s earlier work sounding the alarm on algorithmic systems that make high-risk decisions about people. Emotion AI fits squarely into that category.

Why the Regulator Is Wary of Emotion AI

Let’s get to the legal issue.

Under the GDPR, biometric data is classed as “special category data.” That means it’s subject to tougher rules, especially when it’s being processed to infer sensitive traits like a person’s mood, stress levels, or mental health. Consent needs to be freely given, specific, and informed. That’s a high bar. And often, in practice, it’s not met.

Here’s the real issue: inferring emotions from biometrics may involve profiling under Article 22 of the GDPR, which restricts automated decision-making that has legal or similarly significant effects. So, if a hiring tool reads someone’s voice and decides they aren’t a good cultural fit, you could be stepping into regulatory hot water.

In the AP’s view, these tools are not just inaccurate. They may be inherently incompatible with fundamental rights.

In a public statement (translated from Dutch), the AP wrote:

“Emotion AI systems often lack a scientific basis. Moreover, there is a risk that individuals will be classified or judged based on incomplete or incorrect assumptions about their emotions, leading to discrimination or exclusion.”

That’s a powerful statement from a data protection authority and one with teeth.

Why Founders and Product Teams Should Care

If you are building products that use AI in any way to understand or respond to human behaviour, this matters. Whether you are designing hiring software, retail analytics tools, smart home systems, or emotion-aware chatbots, you could be using or experimenting with tech that falls under the emotion AI umbrella.

Here is what you should be thinking about now:

1. Emotion Inference ≠ Emotion Truth

Let’s be clear: algorithms don’t read feelings; they predict probabilities based on signals. One person’s “frown” might mean they are thinking deeply. Another person’s flat voice might not mean sadness at all.

Designing automated systems that assume emotional meaning from expressions could lead to deeply flawed decisions.

From a legal standpoint, regulators are warning that this interpretive guesswork may not be lawful, especially when it results in profiling or bias.

2. GDPR Does not Like Guesswork

Even if you are not storing the biometric data, just analysing it may trigger data protection obligations. The Dutch consultation makes it plain that emotion recognition tools could violate principles of data minimisation, accuracy, and fairness.

GDPR also requires “data protection by design and by default.” That means you need to consider whether a tech feature should be built at all, not just whether you can get away with it.

So, What Comes Next?

We don’t yet know what the Dutch regulator will recommend in its final report, but if the consultation responses show real public discomfort, we could see:

Official guidance banning certain uses of emotion AI outright.

Clarification that many emotion-recognition applications are unlawful under GDPR.

Joint statements from EU data regulators to align positions across borders.

This would make it harder, maybe even impossible, for companies to deploy emotion AI in recruitment, policing, insurance, education, or advertising without running into enforcement risk.

“But We Just Want to Improve User Experience…”

It’s a common defence. Many developers say they are not making decisions about people, they’re just using emotion AI to personalise content, show empathy, or help users better express themselves.

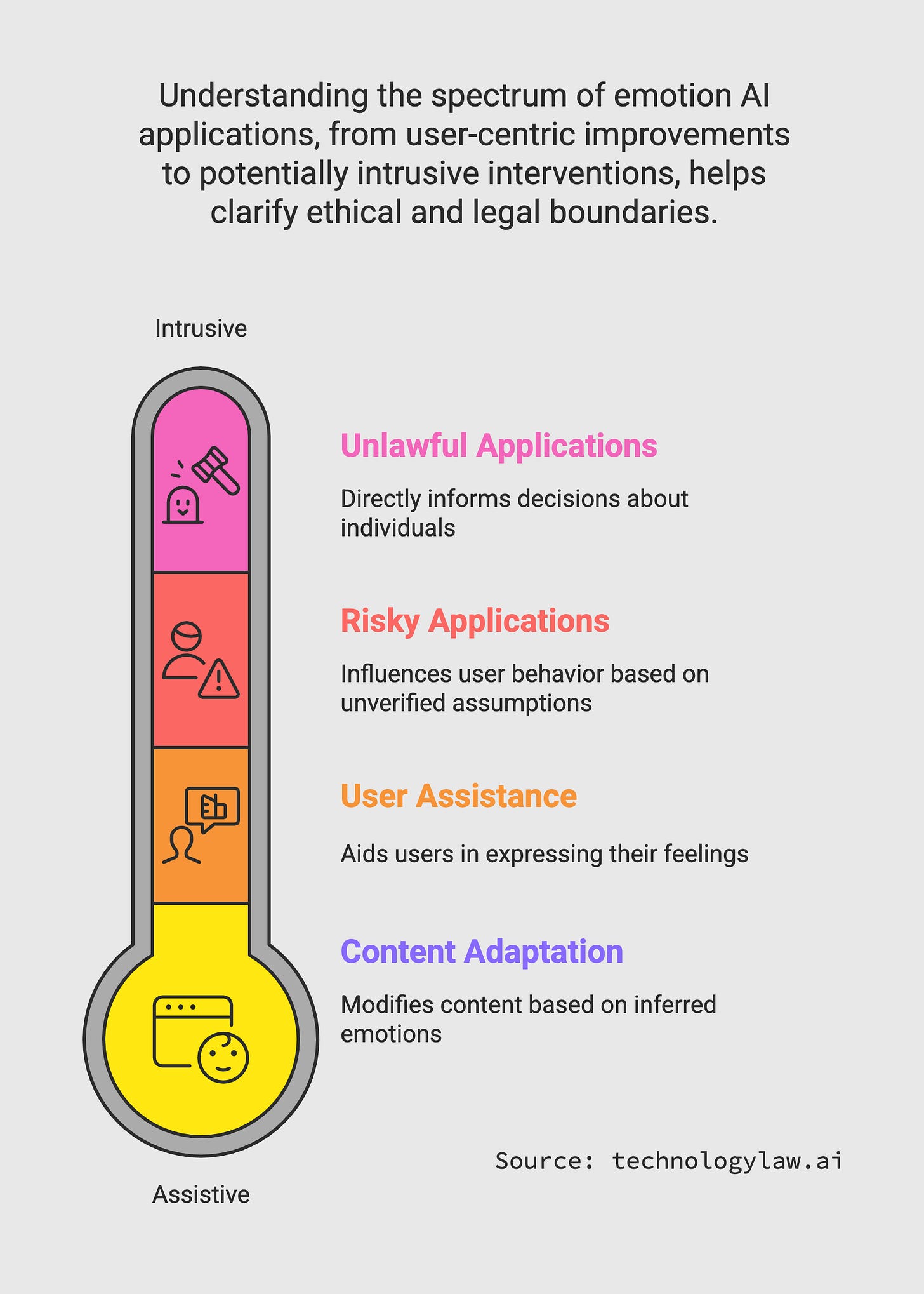

Here’s the problem: the line between assistive and intrusive can get blurry fast. If your app changes its tone because a camera detects “anger” or “boredom,” you may be influencing user behaviour based on an unverified assumption. That’s a risky basis for any tech product—legally and ethically.

The AP’s consultation isn’t anti-innovation. But it is sceptical of AI systems that classify feelings without users understanding what’s being inferred and how it's being used.

What Should Tech Teams Be Doing Now?

Here are a few immediate steps to consider:

Audit your product: Are you using emotional inferences in any way? Even indirectly? Review all use cases involving sentiment detection, voice analysis, facial cues, or biometric inputs.

Check your legal basis: Are you relying on user consent? Is it GDPR-compliant? Would your average user understand what’s being analysed?

Pause pilot features: If you are testing emotion recognition tools, now is a good time to stop and review whether the benefits really outweigh the risks.

Thanks for reading Tech Law Standard. If this update was useful, consider sharing it with your team or co-founders. We are here to help you stay one step ahead of the legal rules shaping tech innovation.

This is one of the most timely and well-articulated analyses I’ve seen on the regulation of emotion AI. Thank you for cutting through the hype and addressing the legal, technical, and human dimensions with such clarity. As someone who follows the ethical architecture of AI closely, I deeply appreciate the emphasis on how inferential guesswork, especially around something as nuanced as emotion, can quietly cross into high-risk territory, both ethically and legally.

The Dutch DPA’s stance feels like a necessary corrective in a space that’s often racing ahead without clear boundaries. Especially valuable was the distinction you made between assistive and intrusive, a line that’s often blurred in the name of UX optimization. This piece is a must-read not just for founders, but for anyone designing with AI in emotionally adjacent domains. Honored to be in this community of critical thinkers.