If AI Is Trained on Your Content Without Permission, What Rights Do You Have? (New York Times v. Microsoft Corporation)

Newsletter Issue 16 (Case Report): The New York Times Company sued Microsoft and OpenAI in court recently.

Big Tech just received a legal wake-up call. In a high-profile case, The New York Times took on Microsoft and OpenAI over how AI tools like ChatGPT learn from online content, and the court's response could define the future of journalism, copyright, and AI itself. Whether you are a creator, a novice tech user, or just curious about how data machines learn from what you read, this case is one you will want to follow, closely!👇

🏛️ Court: U.S. District Court, Southern District of New York

🗓️ Judgment Date: 4 April 2025

🗂️ Case Number: No. 23-CV-11195 (SHS), 2025 WL 1009179

🔍 Legal Issue in New York Times Company v. Microsoft Corporation

In New York Times Company v. Microsoft Corporation, the groundbreaking question was considered: Can tech giants legally use news articles to train artificial intelligence (AI) without permission?

This case pits respected news organizations like The New York Times against Microsoft and OpenAI, creators of powerful AI systems such as ChatGPT.

The journalists from the New York Times allege that their original reporting, often paywalled or copyrighted, was “scraped” and fed into AI systems that now spit out summaries, rewrites, or even near-verbatim reproductions of their work.

Essentially, the media groups are saying: “Hey, that’s our hard-earned content! You didn’t ask, and now you are profiting from it.”

This raises several complex legal issues, such as:

❓ Direct copyright infringement: Did AI developers unlawfully copy the content during training?

🤝 Contributory and vicarious infringement: Are Microsoft and OpenAI responsible for what users do with their AI tools?

🚫 DMCA violations: Was copyright info deliberately stripped from articles to hide the origin?

⚖️ “Hot news” misappropriation: Did the companies unfairly capitalize on time-sensitive news?

🌐 Standing and timeliness: Did the publishers wait too long to bring their claims?

This lawsuit does not just affect journalists or tech firms; it could impact how all of us use and interact with AI-powered tools in the future.

Are we heading for a world where bots can remix anything online without credit or cash? Or will copyright laws be redrawn to protect human creativity in the AI age? 🤔

Material Facts – New York Times Company v. Microsoft Corporation

The New York Times Company, along with Daily News LP and the Center for Investigative Reporting, filed lawsuits against Microsoft and OpenAI, accusing them of misusing their news content to train AI tools like ChatGPT and Copilot.

Between 2020 and 2024, OpenAI developed increasingly sophisticated large language models (LLMs), including GPT-4, which became integrated into Microsoft products such as Bing Chat and Office Copilot. These AI systems were trained on enormous datasets scraped from the internet—datasets that, according to the plaintiffs, included their copyrighted news articles, often taken from behind paywalls.

The media organizations alleged that OpenAI and Microsoft used automated scraping tools to extract and ingest their journalism into the AI training pipelines.

What made this more concerning was the claim that the tools removed or altered copyright management information (CMI), like author names and copyright notices, during the process. The result? Users could ask AI tools about news topics and receive direct answers or summaries that echoed (and in some cases nearly replicated) the original content without attribution or a link to the source.

The plaintiffs presented more than 100 examples of AI outputs that closely resembled or outright quoted their work. Some outputs, they claimed, appeared to “regurgitate” original articles nearly word-for-word, with no mention of the original publisher. This behaviour wasn’t an isolated glitch; it occurred after the tools were publicly released and widely used by millions of people around the world.

🚨 Additionally, the organizations said they had previously informed OpenAI and Microsoft that their systems were displaying copyrighted content, but the practice allegedly continued despite the warnings.

Beyond the technical details, the media outlets said this undermined their business models. Their content, which depends on paid subscriptions, ad revenue, and licensing deals, was being distributed by AI systems for free, bypassing their websites and draining their ability to fund journalism. The organizations argued that this use of their work effectively redirected readers, users, and revenue away from them and toward Microsoft and OpenAI’s platforms📉.

Interestingly, the news outlets didn’t all sue together. The New York Times filed first in 2023, followed by Daily News LP and the Center for Investigative Reporting in 2024. Each lawsuit contained slightly different factual details, but all centred on the same pattern: unauthorized use of copyrighted journalism in AI training and outputs.

In defence, Microsoft and OpenAI tried to dismiss the suits, arguing among other things that the plaintiffs lacked standing or had waited too long to sue. They also challenged whether scraping, training, and AI output even violated any laws. But the court, as of April 2025, found that the news companies had presented enough concrete and plausible facts for the case to move forward.

At its core, this dispute is about more than copyright; it’s about whether news content created by humans can be endlessly absorbed and reshaped by machines without compensation. As generative AI becomes a fixture in daily life, the outcome of this case may redefine how knowledge is owned, used, and valued in a digital-first world.

⚖️ Judgment: 4 April 2025

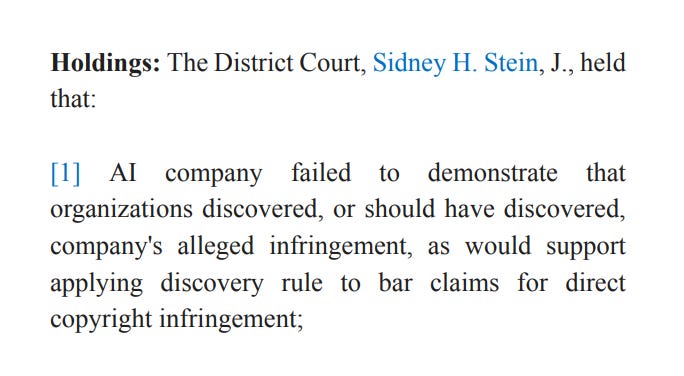

In a closely watched decision that could impact the future of AI and media, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York issued a partial ruling on 4 April 2025, in the case between major news organization, including The New York Times 📰 and tech giants Microsoft and OpenAI 🤖💼.

Judge Sidney H. Stein didn’t rule entirely in favour of either side. Instead, he delivered a mixed decision 🧑⚖️⚖️:

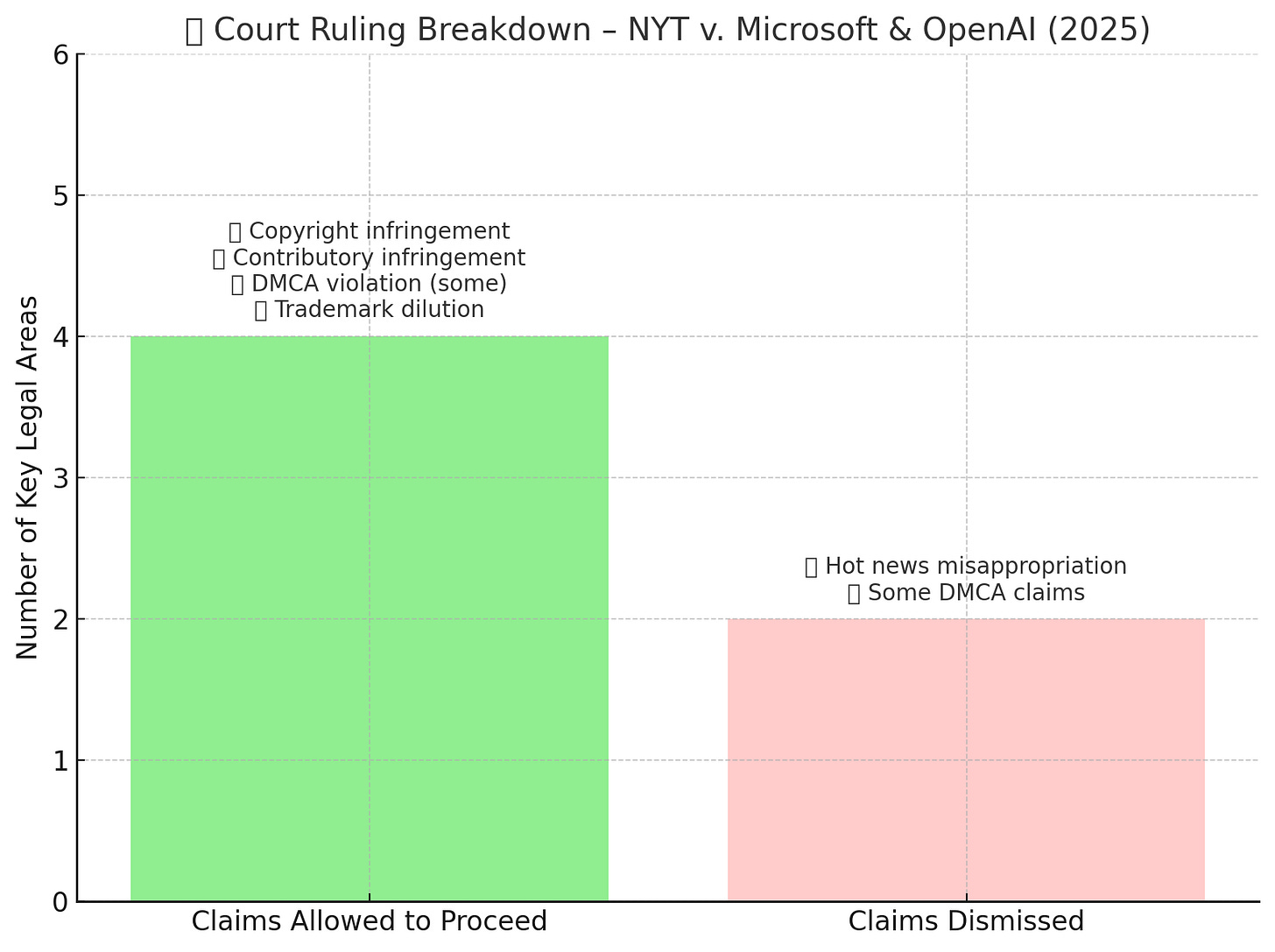

✅ The court allowed several claims to move forward, including those for:

Direct copyright infringement

Contributory copyright infringement

Violation of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA)

Trademark dilution under the Lanham Act

The judge found that the news organizations had laid out enough detailed and plausible facts to justify further legal discovery. That means the case isn’t over, it’s just heating up 🔥.

❌ However, not everything survived the motion to dismiss:

The court dismissed some “hot news” misappropriation claims

It also tossed certain DMCA-related claims where the plaintiffs didn’t provide enough detail about how copyright information was allegedly removed

This ruling doesn’t settle who’s right or wrong; it simply clears the path for the case to proceed to the next phase, where more evidence will be examined, and possibly a trial will occur.

For now, both sides are regrouping. News outlets see it as a victory for journalism, while Microsoft and OpenAI are likely to continue defending how they built their AI systems. The ultimate outcome could have major implications for how AI learns and who gets credit, and compensation, for the knowledge it shares.

🧠 What This Case Teaches Us About AI, Copyright, and Content Ownership

This case is more than a clash between old-school journalism 📰 and new-age tech; it shows us how the law is adjusting (or struggling to adjust) in a world increasingly run by artificial intelligence.

Let’s unpack the key legal principles:

📚 1. Copyright Law Still Matters in the Age of AI

One significant takeaway from this case is simple: just because technology has advanced, doesn’t mean the law disappears. AI developers, no matter how powerful or innovative, must still respect the core principle of copyright: creators have rights over their original work.

In other words, if a human spent hours writing an article, coding an app, designing a graphic, or snapping a photo, that work is legally protected. AI doesn’t get a free pass just because it’s “non-human.” This case reinforced that training machines on creative content still aligns with human rights, the rights of those who made that content in the first place.

📌 Tech companies need to remember that copyright law isn’t optional. It travels with the content, even into the machine-learning era.

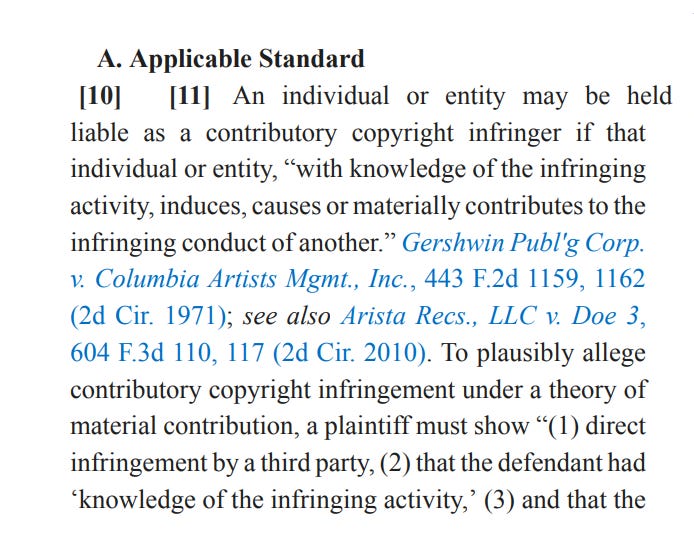

🔁 2. Contributory Infringement: Not Just the User’s Fault

A really important principle revived in this case is contributory infringement, which basically says, if you help someone else break copyright law, you could be liable too.

Even if Microsoft or OpenAI didn’t directly generate or post infringing material, they allegedly created and released tools that allowed users to do so. Courts are now looking at whether the developers knew (or should have known) their tech would be used in this way, and whether they failed to prevent it.

Think of it like this: if you build a printing press and give it to someone, knowing they’re going to use it to make fake money, you could be in trouble even if you didn’t hit “print” yourself.

📌 Companies deploying AI tools must think ahead about how users might misuse them and take real steps to prevent copyright abuse.

🔍 3. You Can’t Strip Away Credit and Call It Innovation

Another big principle here comes from the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA). This law protects not just the content itself, but also the information attached to that content, like who wrote it, when, and what the copyright terms are. That’s called Copyright Management Information (CMI).

In this case, the news companies said their names and copyright notices were stripped when the AI was trained. That’s like someone sharing your artwork and erasing your signature.

Even though AI outputs might look like “original” writing, if the system learned it by consuming someone else’s words and deleting the tags that showed where they came from, that’s potentially a violation of DMCA rules.

📌 Attribution and transparency matter. It’s not just about what you use but how you use it and whether you respect the creator’s right to be identified.

🏷️ 4. Trademark Law Protects Reputations, Not Just Logos

Interestingly, the case also touched on trademark dilution, a principle under the Lanham Act. This part of the law protects famous brands and publishers from having their names misused or watered down in the marketplace.

If AI models produce flawed, biased, or inaccurate content that appears to come from The New York Times or Daily News, it can hurt their reputations, even if unintentionally. The law recognizes that trusted sources earn their reputation, and that misuse of their name, even indirectly, can damage that trust.

🧠 Imagine asking ChatGPT for health advice and it says it came from Mayo Clinic, when it didn’t. That would affect your trust, right?

📌 AI developers need to be careful how content is attributed (or misattributed). Names carry weight and legal protection.

🧭 5. Courts Expect Tech Companies to Act Responsibly

Perhaps the biggest underlying principle is this: being a leader in AI innovation also means taking responsibility. Courts are increasingly open to the idea that if you build and sell AI tools, you need to build in safeguards, not just fancy features.

The law doesn’t demand perfection, but it does expect good faith. That means acknowledging when your product affects other people’s rights, and being transparent when problems occur.

We wouldn’t accept self-driving cars that don’t stop for red lights 🚦so why accept chatbots that don’t pause at copyright boundaries?

📌 As AI tools become part of everyday life, the courts are sending a message: With great tech power comes great legal responsibility.

So apparently, if you feed millions of professional photos into an AI without permission, it might start spitting out your work back at you, just... slightly weirder. Who knew the future of art theft would involve algorithms and half-missing watermarks?