The Data That Trains AI Will No Longer Stay Secret

Newsletter Issue 67: A new legal framework now goThe European Commission now requires companies that develop general purpose AI models to publish a summary of their training data publicly.

The European Commission has decided that the era of hidden training data for general purpose AI models is over. With immediate effect, companies will have to inform the public what kinds of content they use to train these AI models. Some see this as overdue; others fear it will slow AI development.

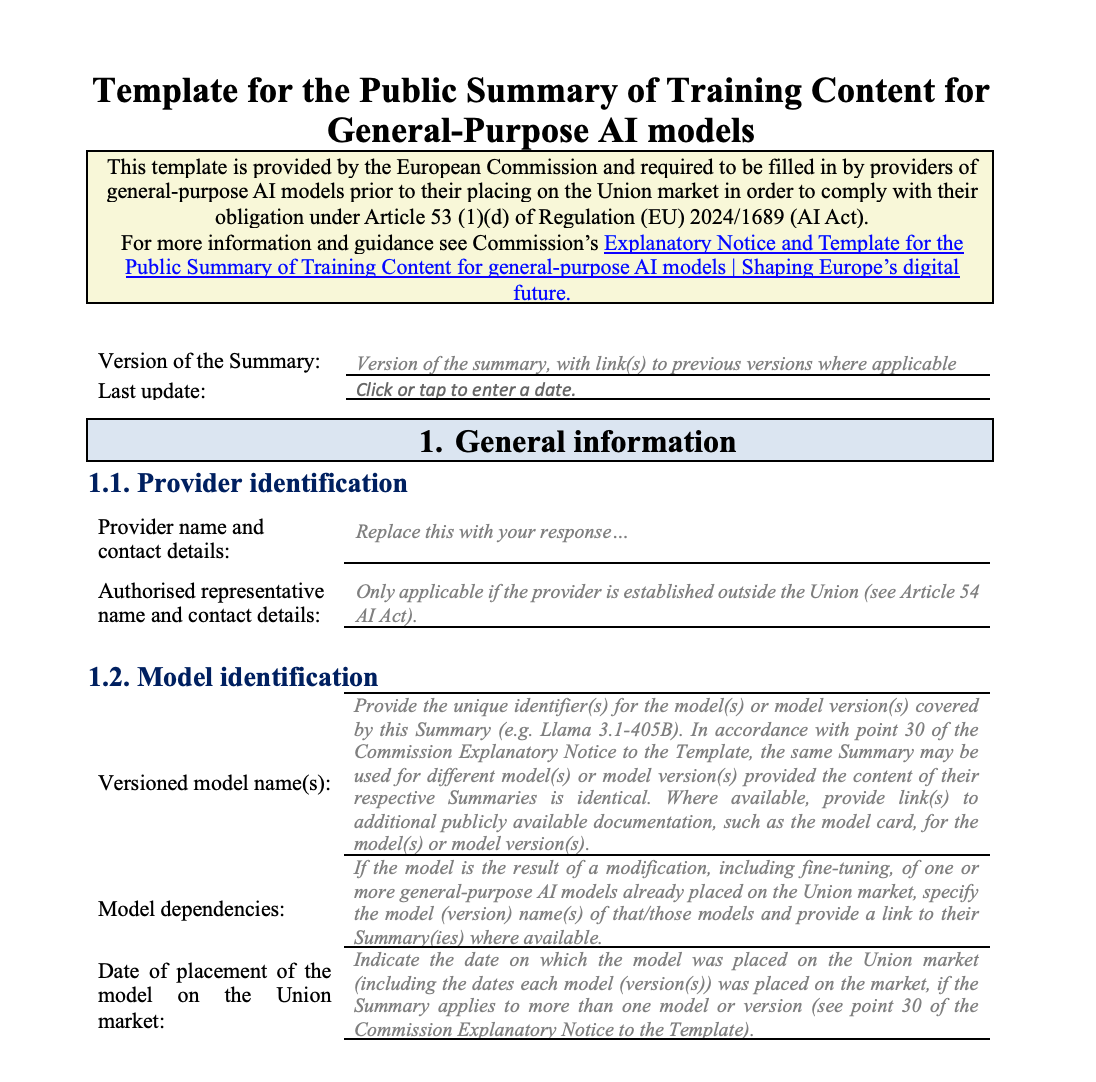

A new template for GPAI from the European Commission

The European Commission (EC) has introduced a structured template that every provider of a general-purpose AI model will now be expected to complete and publish.

This template comes directly from the obligations set out in Article 53(1)(d) of the AI Act, which entered into force on 1 August 2024 and will begin to apply in full from August 2025.

Its purpose is to bring some light to an area that has been largely hidden from view: the nature of the data that is used to train these powerful models.

For years, the creation of large general-purpose AI (GPAI) models has relied on vast amounts of data collected from many different sources.

Until now, the details of this data have rarely been explained in a way that allows the public to understand the kinds of content involved.

The EC’s new template aims to change this by requiring providers to set out, in clear narrative form, what data they have used and where it came from.

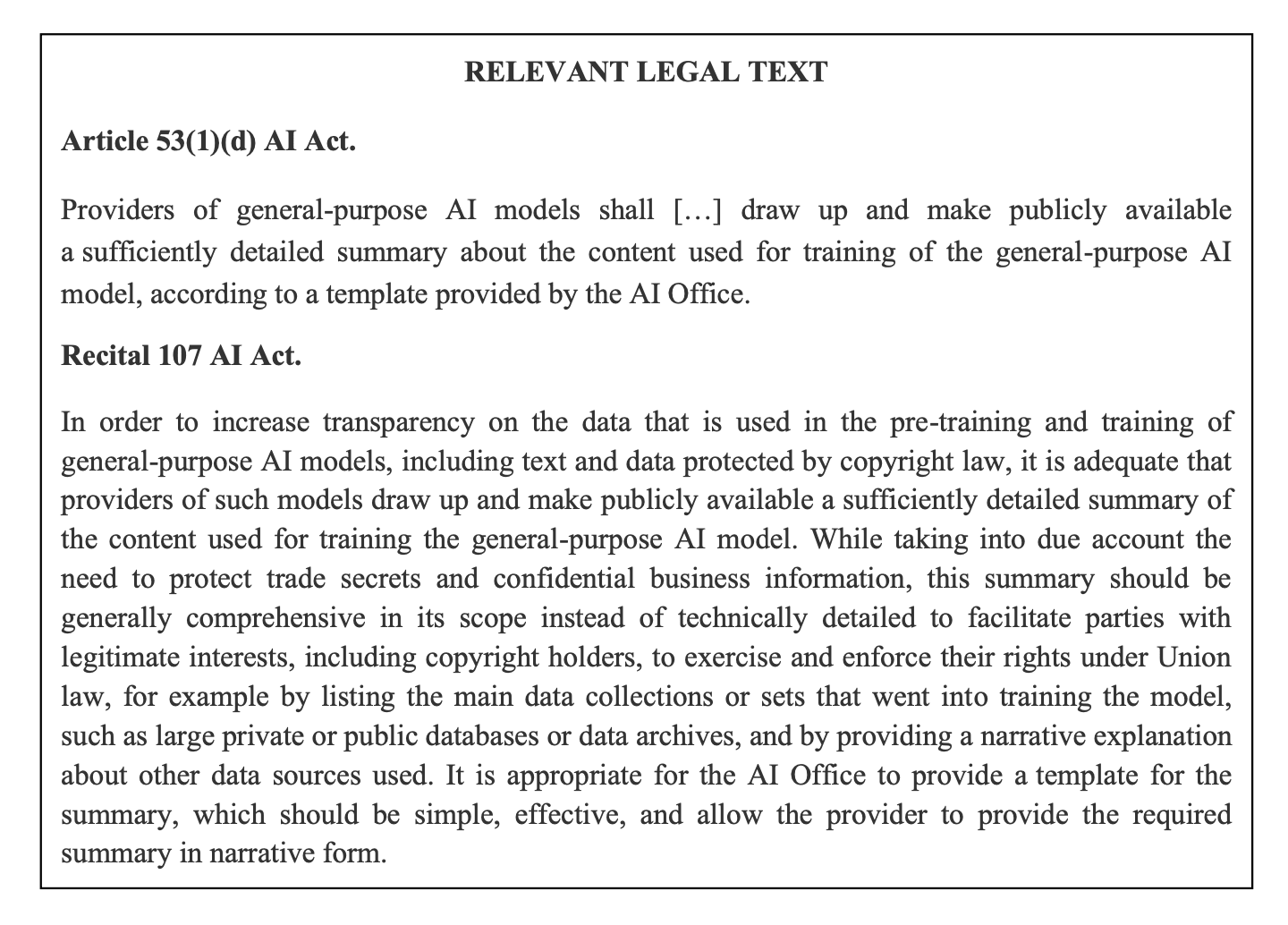

It is not meant to be a technical audit, but to be broad enough to help rightsholders and others with legitimate interests understand how their material may have been used, while also making sure that the most sensitive trade secrets remain protected.

The explanatory notice published by the Commission makes clear that the goal of this new approach is transparency.

The EC hopes to make it easier for authors, artists, researchers, and companies to see whether their data might have been part of the datasets used to train these models.

It also sees value in allowing other developers and downstream users of such models to know whether the data used is diverse and whether certain kinds of content dominate.

This information will become a reference point for copyright concerns, competition issues, data protection interests and the broader question of how these models are developed.

The template itself has three main sections.

The first section concerns general information.

This includes the name of the provider, the models to which the summary relates, the date when the model was placed on the EU market and some description of the data used, such as whether it is text, image, video or audio and the approximate volume of each.

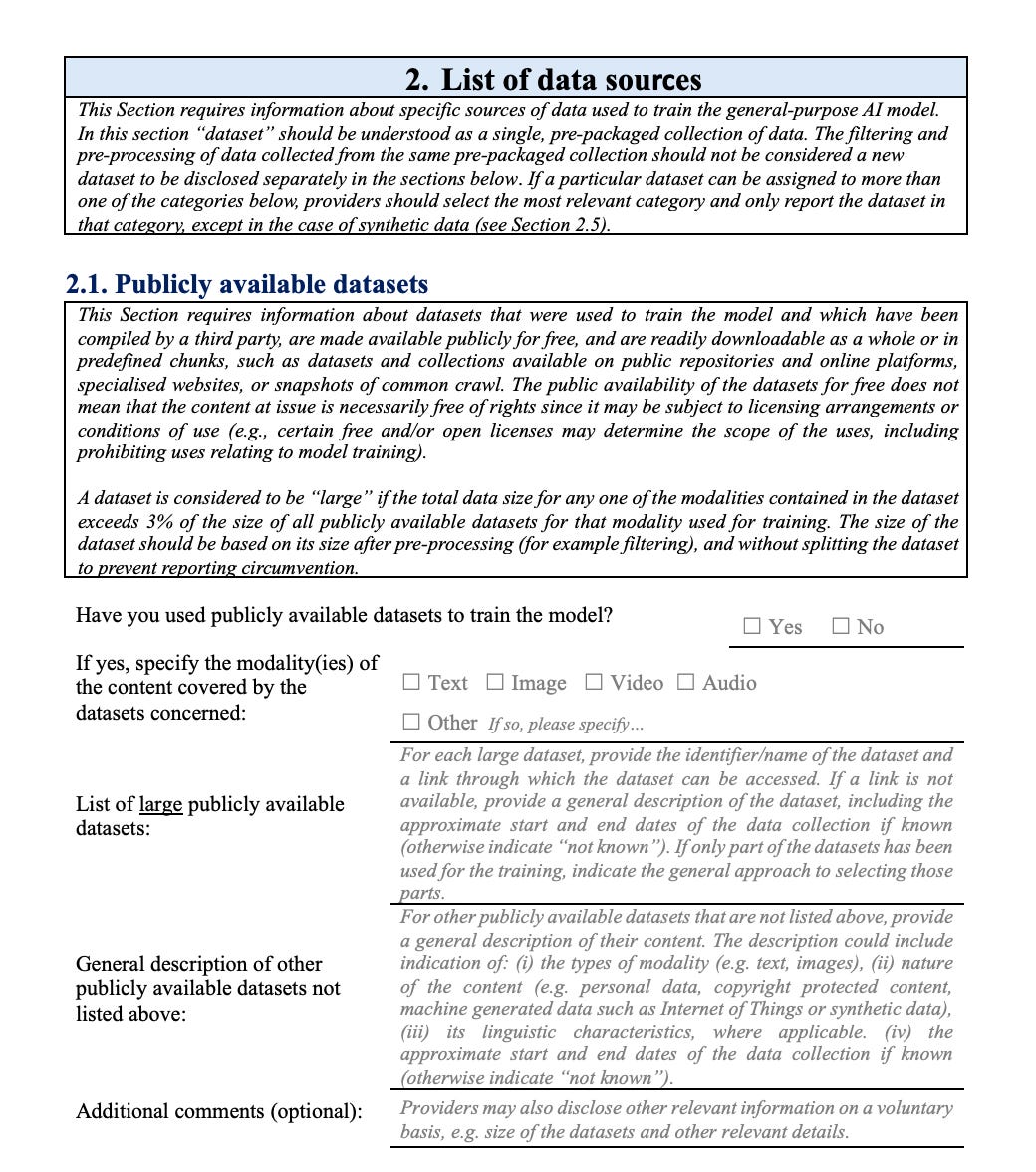

The second section focuses on the sources of data.

It requires the provider to list large public datasets, describe other private datasets whether licensed or not, describe content scraped from online sources, and also explain whether user data and synthetic data were involved.

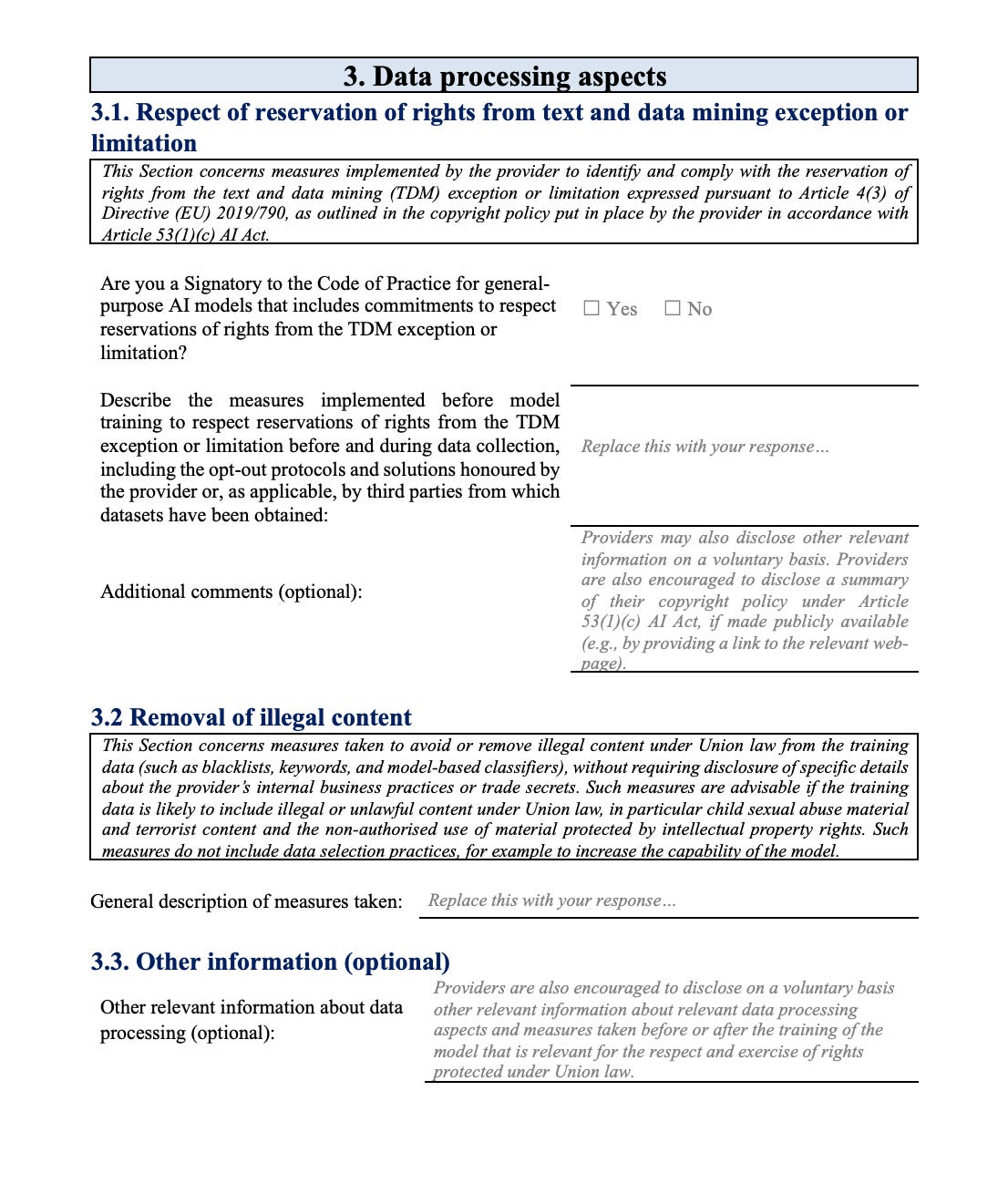

The third section asks the provider to explain how they have handled important issues such as copyright reservations, removal of illegal content, and other information that may affect the rights of others.

This framework is a legal requirement.

Providers that do not publish the summary or fail to fill in the template correctly could face penalties of up to 3% of worldwide annual turnover or 15 million euros, whichever is higher.

The AI Office, the new authority created by the AI Act, will oversee compliance.

The background document makes clear that the template has been prepared after extensive consultation, with over 430 responses from stakeholders across the public and private sector.

It is the result of a deliberate attempt to strike a balance between opening a window into model training and avoiding the release of commercially sensitive data.

Why this matters for transparency

The importance of transparency in the training of general-purpose AI models has been a recurring theme in the discussions surrounding the AI Act, but it now takes a concrete form with the introduction of the public summary template.

The EC has placed emphasis on the fact that these models are trained on vast quantities of data, and yet there is very little public knowledge of what that data actually contains.

The new requirement responds to that absence of information with a structured approach that will allow a clearer picture to emerge of what goes into building models of this scale and influence.

The explanatory notice explains that the summary is designed to give everyone from authors to researchers an opportunity to see in broad terms the types of content that have been used in training.

The template requires that providers list large datasets, describe scraped material from online sources, mention whether user-generated content or synthetic content has been included, and identify the kinds of data that dominate the training process.

This is not about exact file names or technical datasets. It is about providing enough information to make patterns visible.

The Commission states that the objective is to enable parties with legitimate interests to use this information to protect their rights while allowing the public to see the general landscape of data that supports these models.

One of the key benefits of publishing this information lies in the connection to intellectual property rights.

The document sets out that copyright holders will be able to see whether their work may have been used and, if necessary, seek remedies. It also has implications for data protection.

By disclosing the nature of the content used, it becomes easier to see whether personal data has been incorporated into training. For academics and developers who want to evaluate these models, it will provide insight into the breadth and balance of the data sources that shaped a model’s capabilities.

This is why the summary must be published and must be public.

The EC goes further in its reasoning. Greater clarity on training content supports the principle that innovation should not operate in complete secrecy when it has wide societal impact.

It recognises that diversity in training data can reduce risks of bias and discrimination.

By asking providers to make public their choices about sources, it creates a way for others to hold them to account if their approach has been narrow or unrepresentative.

Transparency also has an effect on competition.

If information about how models are trained is made available, smaller players and downstream users can better understand whether a model is built on open material or locked away behind exclusive datasets, reducing the possibility of markets being closed to new entrants.

The publication will become part of the compliance obligations from August 2025.

This requirement applies equally to providers of open source models and to commercial entities, with no distinction.

It has been carefully balanced to avoid exposing confidential information. Providers will be allowed to present the information in broad ranges and narrative form.

Yet, the aim is to make it clear enough so that anyone reading the summary can understand the scale and variety of the content involved.

Balancing openness and confidentiality

The EC has been careful to build a framework that allows the public to gain insight into how general purpose AI models are trained, while at the same time recognising that the details of data selection and model construction form part of a company’s commercial advantage.

The explanatory notice behind the template repeatedly draws attention to this balance and explains how it has been reflected in the structure of the document that providers will be required to complete.

Recital 107 of the AI Act is the starting point. It explains that summaries must be comprehensive but not technically detailed.

The EC wants everyone to understand the overall picture of where data has come from without having access to precise datasets, exact selections or the commercial decisions that went into curation.

The template uses this principle in each section.

For example, large publicly available datasets must be identified by name, but only when their use is obvious and already public.

Private datasets that are not publicly known do not have to be named, but providers must give a general description of their contents so that readers can see what kind of material was involved without the source being revealed.

For online data that has been scraped, the template requires a list of the most relevant domains, covering a top percentage of sources rather than every website.

It also asks for a description of the type of sites involved and the period of collection.

These are details that can give the public a clear sense of how broad the model’s training has been while avoiding publication of every individual file or page.

Synthetic data and user generated content receive similar treatment.

The AI model provider must say whether these categories were used, and in the case of synthetic data must identify any models that generated it, but is not asked to disclose exact quantities or specific content.

The EC explicitly recognises that data licensing agreements are often confidential and so these need only be disclosed in very general terms, without giving away the specifics of any contract.

Where providers have used licensed content, they simply confirm that these agreements exist.

By adopting a structure that focuses on categories, broad ranges and narrative description rather than precise disclosures, the EC has created a way to respect the importance of trade secrets.

At the same time, it has provided a means for the public, for rightsholders, and for researchers to learn enough about the scope and nature of training data to make informed assessments of the models.

This is a legal obligation rather than a courtesy and the text makes it clear that failure to meet it can attract serious sanctions, but the detail has been carefully calibrated to avoid creating an obligation that undermines innovation.

The document is a generous compromise between two interests that have previously been set against one another.

TL;DR

1. Public summaries for AI training data: From August 2025, all providers of general-purpose AI models in the EU must publish a public summary of their training data content using a new European Commission (EC) template. This applies to commercial and open-source models alike, ensuring clarity about the sources used in AI model development.

2. Purpose of the new summaries: The summaries aim to bring transparency to data used for AI training. They help rightsholders enforce intellectual property rights, support data protection, and assist researchers, users, and regulators in understanding the diversity and scale of content used, without listing every individual file or dataset.

3. Scope of data to be disclosed: The summaries cover all stages of AI model training, from pre-training to fine-tuning, and include text, images, audio, video, synthetic data, and user-generated content. Providers must describe the types of data and sources involved rather than share exact technical details or datasets.

4. Balancing openness and confidentiality: The template is designed to avoid disclosure of trade secrets. It asks for categories and narrative explanations, for example, listing major datasets or the most relevant scraped domains, but avoids forcing companies to reveal precise mixes of data or confidential licensing arrangements.

5. How the summaries will be checked": The AI Office will supervise compliance, ensuring providers fill out the template correctly. Non-compliance may result in penalties up to 15 million euros or 3% of global annual turnover. Providers must update summaries regularly if models are retrained or modified after being placed on the market.

6. Publication and transitional rules: Summaries must be published on the provider’s website and with the model at release. For models launched before 2 August 2025, summaries must be made public by 2 August 2027. Providers must explain if certain historical information is unavailable due to practical limitations.

The conversation around transparency in general purpose AI models is only beginning. These new summaries open the door to better understanding and oversight. Your thoughts and perspectives on how this will influence innovation and accountability are welcome. Comment on this newsletter and join the discussion.

If you place an AI model in the EU market after August 2025, you must publish a summary of the data that trained it. These summaries will be updated as models evolve. They cover books, images, audio, video, scraped content, and user input. Companies can protect trade secrets but they must explain sources in plain language.

https://open.substack.com/pub/hamtechautomation/p/corporate-and-government-battle-for?r=64j4y5&utm_medium=ios