Legal Update: They Tax the Phone, the Data, and the Service

Taxes on digital service providers can be costly and occasionally prohibitive. These crippling taxes raise costs and limit access to digital services in poor communities.

Digital services feel like they should be getting cheaper, but in many countries, the opposite is happening. Hidden taxes on everything from streaming (e.g., Netflix and Amazon Prime) and mobile data to smartphones are being used systematically to make digital services costly for some of us. This newsletter takes a closer look at how digital services taxation works, who really pays, and why these rising costs are affecting some communities more than others.

A Reflection on Digital Services Tax

We cannot really embark on discussing the digital services tax system without first analysing the expansive report recently published by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) in April 2025.

It is necessary to note that the World Telecommunication and Information Society Day (WTISD) was observed on 17 May 2025, marking the 160th anniversary of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) founded in 1865.

The WTISD is noteworthy in information and communication technologies (ICTs) as a day celebrated to support global connectivity and telecommunication development efforts. It highlights a longstanding commitment to bridging the digital divide and promoting inclusive digital transformation.

The 2025 WTISD theme, "Gender Equality in Digital Transformation," focuses on the need for inclusive policies that address disparities in digital access and participation. This focus aligns with the ITU's broader objectives of ensuring that technological advancements benefit all segments of society, particularly marginalised groups. Legal measures play a crucial role in this context, as they can mandate equitable access, protect digital rights, and promote diversity in the tech industry.

The ITU's April 2025 report on digital services taxation, the main focus of this newsletter post, further illustrates the objective. The report highlights how certain tax laws can inadvertently increase the cost of access to digital technologies, thereby exacerbating the digital divide. The ITU advocates for legal reforms that balance revenue generation with the need to make digital services affordable and accessible .

WTISD encourages international cooperation in developing legal frameworks that support innovation while safeguarding the rights and interests of all users (i.e., consumers).

The ITU's April 2025 Digital Services Tax report provides one of the most comprehensive analyses to date, comparing how taxes affect both providers and users of digital platforms and telecommunications services.

The report explores a wide range of tax types.

These include general corporate taxes such as profit tax and value-added tax, as well as sector-specific charges like regulatory fees, spectrum licence costs, and import duties on network equipment and consumer devices.

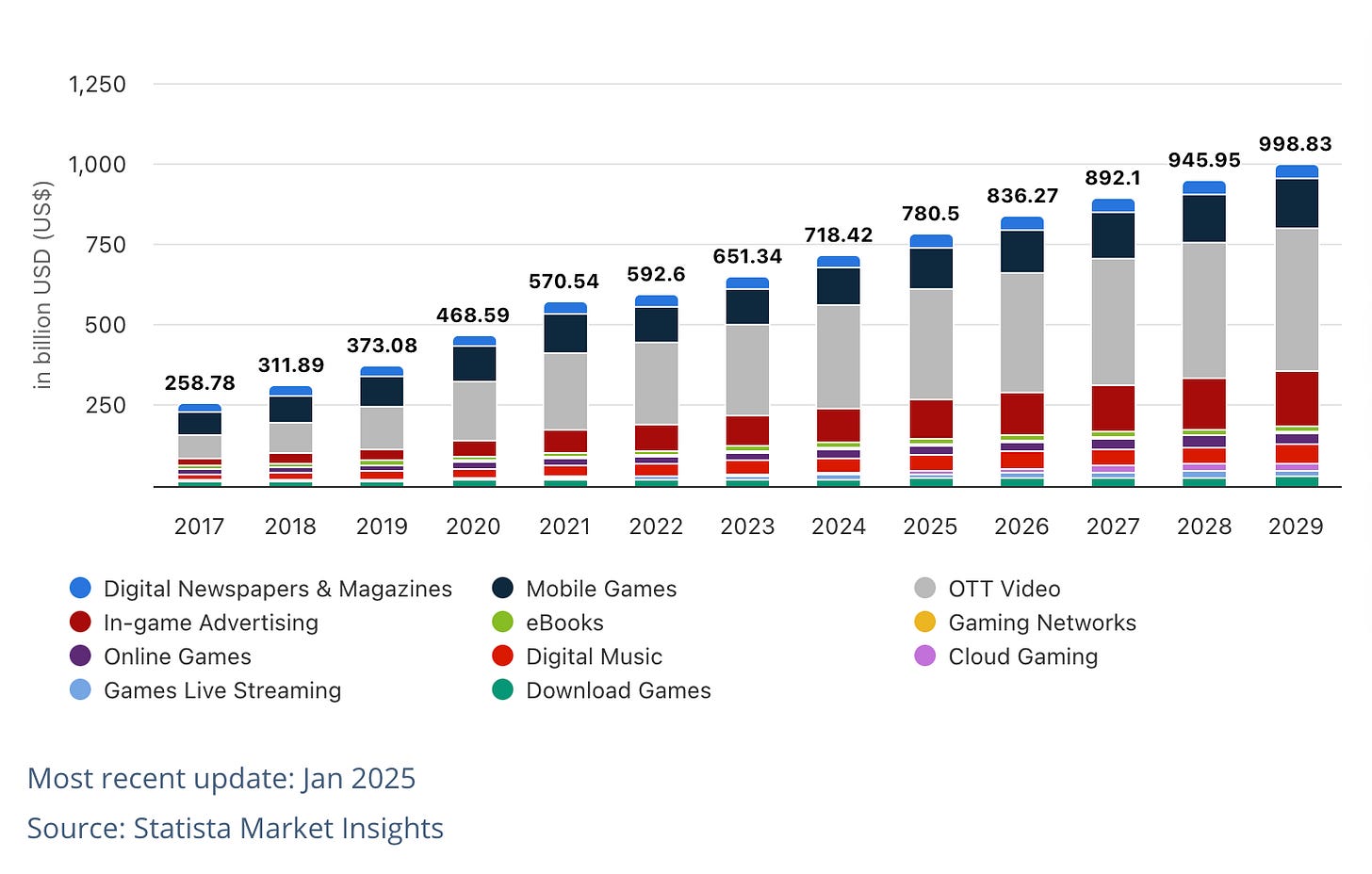

It also looks at taxes applied directly to digital platforms and to the consumption of services such as internet access, mobile data, and streaming subscriptions.

Rather than taking a narrow or technical view, the ITU’s report investigates how these taxes influence the real-world cost of accessing digital tools and services. It reveals major inconsistencies in how different countries apply these taxes, and it highlights the risks high taxes pose to affordability, digital inclusion, and infrastructure investment.

Through its findings, the report provides governments and regulators with practical insights into how smarter tax design could support a more equitable and connected digital future.

This newsletter provides an in-depth critique of the ITU Digital Services Tax report for the benefit of consumers who use digital services daily with limited knowledge of undisclosed taxes associated with their use.

🤔 What is a Digital Services Tax (DST)?

Digital Services Tax, often called DST, is a type of tax that governments apply to companies offering digital services.

These include online advertising, video streaming, e-commerce platforms, social media, and other services that operate through digital networks.

DST targets the revenue generated by these services within a country, even if the company offering them is based elsewhere.

The reason many governments have introduced DST is to address what they see as a gap in the traditional tax system. Digital companies can operate and earn significant income in a country without having a physical presence there.

Under older tax rules, this allowed them to pay very little or no tax in the countries where they had many users or customers. DST aims to correct this by taxing part of their revenue locally.

DST usually applies to gross revenues, not profits.

This means the DST is calculated based on the total income from digital services, without considering expenses. It is generally aimed at large multinational companies, especially those with global operations and high revenues.

For example, a country may only apply DST to companies earning over a certain amount globally and locally.

While the tax is collected from the companies, the impact often reaches consumers. Companies may increase prices or reduce services in markets where DST is applied. This means consumers might pay slightly more for subscriptions, products, or digital ads, depending on how companies respond to the tax.

There is no global agreement on DST. Each country applies its own rules, tax rates, and thresholds.

In France, for example, the DST rate is 3 percent. The United Kingdom applies a 2 percent rate on digital services used by UK residents. India introduced a tax called the Equalization Levy, focused on foreign digital providers.

The debate around DST continues. Some countries see it as a fair way to collect revenue from global tech companies. Others believe it creates trade tensions and complicates international tax cooperation. Still, the number of countries introducing DST continues to grow.

🛜 Online Streaming, Surfing, and Paying: How You Are Already Being Taxed

Digital taxes affect how we pay for online services. Consumers are now paying more for everyday digital activities such as watching films, listening to music or making voice calls through the internet. These taxes are quietly included in subscription fees and service bills, making digital services more expensive.

A common form of this taxation is the value-added tax (VAT). Many governments apply VAT to digital platforms such as video streaming services, online advertising, cloud storage and digital marketplaces.

When people subscribe to services like Netflix, Amazon Prime or Spotify, they are often paying VAT on top of the listed price. This is also true for services provided by companies that do not have a physical presence in the country. Countries such as Australia, Japan and the United Kingdom have already put in place rules that require foreign digital service providers to collect and remit VAT.

Mobile data usage and voice services are also taxed. In some countries, users pay a set percentage of their monthly mobile phone bills as a tax. Others add specific taxes for each minute of voice calling or for the amount of data used. Some countries impose additional taxes on international calls, whether incoming or outgoing.

Buying a smartphone or tablet also involves taxes. Many governments impose customs duties and VAT on imported devices. These taxes increase the retail price of the devices, making access to digital tools more expensive for ordinary users. In several developing countries, import duties are especially high, further limiting affordability.

Digital taxes (i.e., DST) have expanded to cover many aspects of internet use. Governments see digital services as a growing source of revenue. As a result, the cost of using these services continues to rise for consumers around the world.

The effect is that even simple digital acquisitions come with tax obligations. Watching a film, using social media or making an international voice call now involves tax-related charges that may not be obvious.

📊 The Corporate Side: What Tech Companies Really Pay

Behind the services many people use every day lies a web of taxes that technology and telecommunications companies must pay to keep things running. These costs are not limited to profit taxes. According to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), digital operators are taxed across several layers, often in ways that affect their ability to invest in infrastructure.

First, like any business, digital operators pay profit tax, value-added tax (VAT) and labour contributions. In many countries, however, governments add sector-specific taxes.

One of the most significant is the spectrum licence fee. This is the payment a telecom company makes to use wireless frequencies. Depending on the country, this fee can range from 0.6 percent to 3 percent of a company’s mobile market revenue. These fees can be one-time or recurring, depending on how the licences are allocated and the duration of use.

Telecom companies also pay regulatory fees.

In some countries, these fees are calculated based on a percentage of gross income and can go as high as 7.5 percent. The global average is closer to 0.1 percent, but there are major outliers. These fees are supposed to fund the activities of national regulators, though the scale of the charges can vary widely.

Another major cost is the contribution to the Universal Service Fund (USF).

These funds are designed to expand access to digital services in underserved areas. The international benchmark is about 1 percent of gross income, but in some countries, the contribution is 4 percent or more.

Other expenses include customs duties on imported network equipment, such as antennas and servers, which are still levied in many developing countries. Countries like Kenya and Sierra Leone impose equipment import duties of 25 percent or more. These duties make it more expensive for operators to build and upgrade their networks.

Additionally, some governments impose taxes on each SIM card sold, fees for assigning phone numbers, and even environmental or local permit fees for infrastructure such as mobile towers.

The cumulative impact of these taxes reduces the capital available for investment. According to the ITU report, this can slow the expansion of digital infrastructure, especially in rural areas where the costs are already higher.

Not All Taxes Are Created Equal

The way digital services are taxed varies widely from one country to another. Some governments apply high corporate taxes on digital platforms and operators, while others offer exemptions to encourage investment.

There is no unified global system for taxing the digital economy. This leads to uneven treatment of services, users and companies depending on where they are based or where they operate.

For example, France applies a 3 percent digital service tax on revenue from digital advertising and online platforms, targeting large international firms with significant local earnings. In contrast, countries like Qatar or Kuwait report no sector-specific taxes on telecom services and digital platforms. The same Facebook ad may be taxed in one place and untaxed in another, depending entirely on local tax laws and political priorities.

Some countries rely heavily on taxes as a source of public revenue and apply them broadly to digital services, including voice, data and internet subscriptions. Others choose to reduce or eliminate taxes on digital services and equipment to support broader goals such as digital inclusion or economic competitiveness. This explains why mobile users in Zimbabwe face a 15 percent VAT on internet services, while users in Bahrain pay only 10 percent.

The ITU report shows that spectrum licence fees can also vary greatly. In some countries, the payments are minimal, while in others they can reach up to 3 percent of mobile revenue.

Similarly, regulatory fees can be as low as 0.1 percent of income, but can reach 7.5 percent in places like Ecuador. These differences can influence where companies invest and how much users end up paying for services.

There is no clear divide between developed and developing countries when it comes to tax levels. Some low-income countries charge minimal taxes to encourage growth, while others apply high taxes to raise public funds. Advanced economies are just as inconsistent. Australia and Japan, for example, apply moderate tax rates, while Argentina and Mexico impose some of the highest profit tax burdens on telecom operators.

The ITU finds that such fragmentation can discourage cross-border investment and complicate service delivery for international firms. When tax regimes are unpredictable or too complex, companies may avoid markets altogether or pass higher costs to users. The report recommends more coordination across countries to prevent inefficiencies, improve fairness and reduce barriers to digital growth.

Operators Get Taxed, Then So Do You, Sorry

Digital service taxation affects consumers in more ways than one. Telecom operators, for example, pay a wide range of taxes that are often quietly passed along to the public in the form of higher fees and reduced service quality.

According to the ITU’s April 2025 report, the financial obligations on telecom companies include corporate profit taxes, spectrum licence fees, regulatory levies, equipment import duties and contributions to Universal Service Funds (USFs).

Operators are taxed when they buy and import network equipment. They are also charged regulatory fees, which in some countries reach up to 7.5 percent of their gross income. The Universal Service Fund requires some providers to give up as much as 4 percent of their income to fund public access in rural areas.

Although these measures are designed to support public services, the combined effect is a reduction in the capital that operators can use for expanding networks or improving services.

Telecom companies typically do not absorb all these costs. Instead, they pass them on to consumers. This is visible in the prices people pay for mobile and broadband services, SIM card activation, international voice calls and mobile data use.

Consumers also pay VAT on services, which can reach up to 25 percent in some countries. In addition, excise taxes and service connection fees are applied in various regions, increasing the total cost of access.

Handset purchases are not spared. Import duties on mobile devices are built into the retail prices, making phones more expensive. In several developing countries, the tax rate on imported devices is high, which further limits access to mobile technology for low-income users.

This dual-tax system places pressure on both operators and end users. Operators have less incentive and capacity to invest in expanding digital infrastructure.

Consumers, especially in developing regions, face higher costs for basic connectivity.

According to the ITU, this structure not only risks slowing down digital adoption but can also widen the digital divide in areas that most need affordable internet access.

For policymakers, the takeaway is clear. Overlapping and excessive taxes may serve short-term revenue goals but ultimately affect affordability, limit investment and reduce digital inclusion.

💰 Making Digital Taxes Fairer

The ITU report highlights several practical steps that countries can take to improve how digital services are taxed. These recommendations are based on both data trends and expert insights, including findings from the ITU’s Economic Experts Roundtable.

First, there is a strong case for reducing sector-specific taxes and regulatory fees. In many countries, these fees are charged as a percentage of the gross income of telecom or internet service providers. In some cases, this can go as high as 7.5 percent, well above the international average. The ITU argues that lowering these fees would help service providers invest more in expanding networks, especially in rural or low-income areas.

Second, the report points to high import duties on network equipment and consumer devices as a barrier to affordable internet access. While some countries have eliminated these duties to support digital expansion, others continue to impose them at high rates. These costs are typically passed on to consumers, raising the price of devices and services. The ITU recommends reducing or removing these import duties to lower consumer costs and encourage wider use of digital tools.

The experts also stress the importance of tailoring tax frameworks to local conditions. This means allowing local or sub-national governments to design tax incentives that specifically address gaps in rural digital infrastructure. For example, reduced tax rates in underserved regions could help attract private investment in broadband deployment.

Another area for reform is the Universal Service Fund (USF). In some countries, contributions to the USF are mandatory and can reach up to 4 percent of gross income. While these funds are intended to support digital inclusion, the ITU notes that they are often poorly managed. It recommends either reforming the way the funds are administered or allowing operators to choose between contributing to the fund or directly building infrastructure in underserved areas.

Overall, the ITU encourages governments to think beyond revenue collection. Excessive or poorly targeted taxes reduce investment in digital infrastructure and make internet access less affordable. If countries want to close the digital divide and promote inclusive growth, their tax systems must reflect those goals.

Digital Divide or Digital Drain?

Access to the internet is essential for education, communication and economic participation. However, the cost of that access remains too high in many parts of the world. One of the main reasons is taxation.

As shown in the ITU 2025 report from the International Telecommunication Union, taxes are making broadband and digital services more expensive, particularly in developing countries.

Consumers in these regions often pay multiple layers of tax. The most widespread is the value-added tax (VAT), which is applied to mobile and internet services in over 140 countries. In some African countries, the VAT rate on digital services can reach up to 20 percent. On top of this, many governments impose additional levies such as service connection fees, fixed telecommunication-specific taxes, and excise duties based on data or voice usage.

These taxes can make internet and mobile services unaffordable for low-income populations.

The report confirms that higher taxes on services reduce demand, especially among price-sensitive consumers. In several developing countries, import duties on smartphones and devices are also extremely high.

These duties are often passed on to consumers in the form of higher retail prices. According to the ITU, no country in the study exempted consumer devices from both import duty and device-specific taxes.

Taxes are also imposed on telecom operators. In some developing countries, regulatory fees and spectrum licence payments are significantly higher than international benchmarks.

These fees reduce the funds available for network expansion. When operators face high tax burdens, they often limit infrastructure investment, which slows down the rollout of broadband in rural and remote areas.

Universal Service Funds (USFs) are one tool used to address the digital divide. Operators contribute a portion of their income to these funds, which are meant to expand services to unconnected areas. But in many developing countries, these contributions can reach up to 4 percent of gross income, well above the 1 percent international benchmark. If not carefully managed, these levies can become just another tax, reducing the capital available for real deployment.

The ITU concludes that if governments want to close the digital divide, they need to revise tax laws. Reducing import duties on devices, lowering VAT on broadband services, and eliminating distortionary fees would help increase affordability and promote inclusion. Equitable taxation is not just a fiscal issue. It is a digital rights issue.

In many developing countries, mobile data and internet use are taxed at higher rates than in wealthier countries. Some consumers in these countries pay VAT, import duties on phones, plus additional service taxes, all at once. This means that the cost of simply getting online can take up a much bigger slice of a person’s income without them even knowing. One solution could be for Universal Service Funds (USFs) to become more transparent, efficiently used, and regularly audited. Many developing countries require telecom operators to contribute a portion of revenue to USFs, but the funds often sit unused or mismanaged. Governments can improve this by tying fund usage to measurable outcomes like rural broadband expansion and by inviting private sector financing. A clear framework at a policy level would help ensure that USFs actually achieve their goal: expanding affordable digital access where it is needed most.