New AI Arbitrator Arrives, ISO Builds Governance Architecture, and EU Experts Redefine General Purpose Models

Newsletter Issue 80: This newsletter explores AI in arbitration, ISO’s responsible AI standards, EU compliance tools, and JRC’s framework on modified AI models.

Welcome to this week’s edition of the Technology Law Newsletter. This week looks closely at four significant updates: the AAA-ICDR’s plan to launch an AI-native arbitrator, the ISO’s new policy brief on responsible AI standards, the EU’s AI Act Compliance Checker, and the JRC’s new framework for classifying modified general-purpose AI models.

1. The Launch of an AI-Native Arbitrator by American Arbitration Association: International Centre for Dispute Resolution (AAA-ICDR)

A significant development in the dispute-resolution domain has taken place: AAA-ICDR has announced that it will launch an “AI-native” arbitrator, initially applied to documents-only construction cases from November 2025.

The AI legal tool is trained on more than 1,500 construction law awards and refined with expert-labelled examples, to ground its decision-making in prior arbitrator reasoning.

The system uses a structured legal prompt library and conversational AI to deliver draft awards and recommendations, but it is explicitly embedded within a “human-in-the-loop” framework: human arbitrators review and validate outcomes before any final award is issued.

Initially, the deployment is limited to documents-only construction cases where the volume is high and the process largely transactional. Further roll-out to insurance and other dispute types is indicated.

Significance of this development

From a legal-operational perspective, this shows that ADR providers are embracing advanced AI systems not merely as adjuncts, but as central to the adjudication workflow.

This development raises immediate considerations: how does one draft arbitration clauses that anticipate AI-native arbitrators?

How do parties assess fairness, transparency, and evidential parity when an algorithmic actor participates in a legally binding decision?

The human-in-the-loop framing addresses the duty of care, but questions of explainability, bias, data governance and procedural fairness remain salient.

Moreover, the focus on high-volume, document-only contexts suggests a deployment model where cost-efficiency and speed are drivers, a marker for where “AI first” approaches may get traction in legal services.

Ethical obligations for arbitrators and counsel remain unchanged: competence, impartiality, confidentiality and independence remain foundational. The association’s own principles reinforce that technology must not supplant these duties.

Data provenance and model training become part of the governance equation: the tool was trained on prior arbitral awards, but parties might ask how representative that dataset is, how the model reasons, whether there is auditability and recourse.

Liability questions will emerge: though humans review the output, reliance on a draft generated by an AI raises potential issues around decision-making attribution and oversight.

Contract drafting and dispute resolution strategy will adjust: parties may want to negotiate explicitly on how an AI arbitrator is used, what review rights exist, whether a traditional arbitrator may override, and how reasoning transparency is ensured.

The AAA-ICDR announcement marks a milestone in legal-tech integration: AI moves from adjunct tool to core component of dispute resolution.

Legal professionals should prepare for change in ADR protocols, model training and contract drafting.

2. International Organization for Standardization (ISO) Policy Brief on Standards for Responsible AI Development and Governance

ISO has issued a policy brief titled Harnessing International Standards for Responsible AI Development and Governance (Publication 100498) that underlines the role of standards in bridging the gap between high-level principles and operational implementation.

The policy brief emphasises that standards provide a common language for developers, governments, regulators and users, helping to translate abstract ethical and policy objectives (such as transparency, fairness, accountability) into technical requirements, benchmarks and conformity-assessment frameworks.

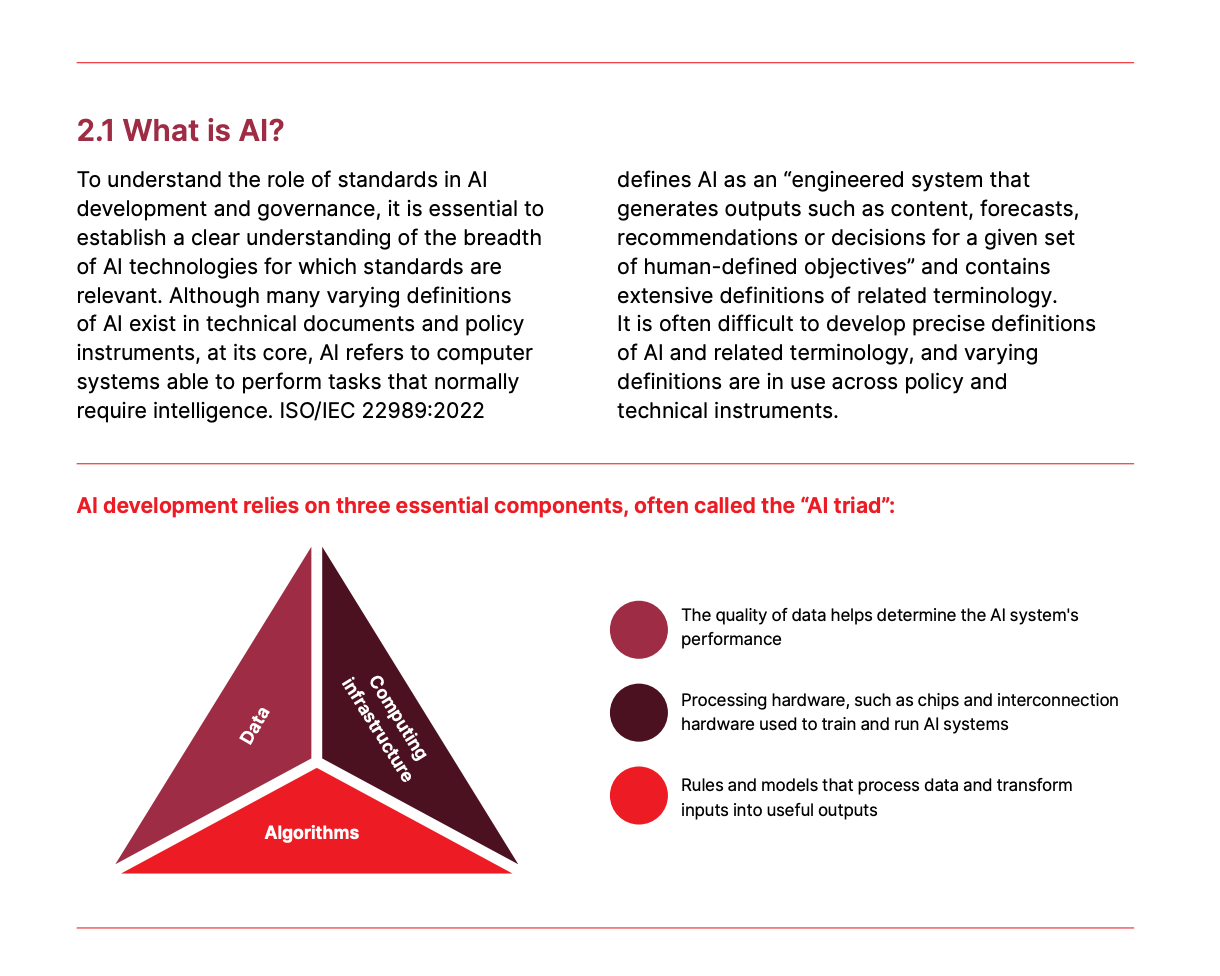

It discusses the socio-technical nature of AI-systems: the interaction of algorithms, data, hardware, institutions, human users and societal norms.

It highlights existing standards under the ISO/IEC umbrella (such as ISO/IEC 42001: AI management system; ISO/IEC 42005: AI system impact assessment; ISO/IEC TS 12791: treatment of unwanted bias) and emphasises that while the pace of AI development is fast, consensus-based standards create a reliable baseline.

The document provides targeted recommendations for policymakers, standards bodies, industry stakeholders and civil society.

While adherence to standards remains voluntary in many jurisdictions, regulators often use standard-referencing as a mechanism to define due-care, conformity, and safety benchmarks.

In contracts, procurement, governance frameworks and compliance assessments, referencing ISO standards will enhance legal robustness.

For organisations deploying AI systems, the policy brief offers a roadmap: not just to comply with regulation, but to implement management systems, assess impacts, mitigate bias, manage data quality, ensure transparency, and enable oversight.

The emphasis on lifecycle (from conception to retirement) is useful for legal counsel advising on AI governance frameworks or vendor contracts.

Legal-governance take-aways

Organisations should evaluate whether they are aligning with AI standards: e.g., has an AI management system been documented and maintained? Are impact assessments conducted? Are bias-mitigation controls in place?

Tendering, procurement and vendor contracts should include provisions linking to relevant standards (e.g., ISO/IEC 42001) to clarify responsibilities and bench-marks.

Regulators may rely on standard-referencing to define compliance thresholds; hence organisations should map standard-coverage to regulatory obligations to reduce surprise risk.

Legal teams should monitor updates to key standards and how they are referenced in national laws or sector-specific regulation, particularly in high-stakes sectors such as finance, healthcare, or transport.

The ISO policy brief reinforces the rising importance of standardisation in AI governance and clarifies how legal frameworks and corporate governance will increasingly lean on standards as reference points.

3. The Launch of the EU Artificial Intelligence Act Compliance Checker Tool

The European Commission and associated bodies have made available an interactive tool (often labelled the “EU AI Act Compliance Checker”) to help organisations determine whether their AI systems fall under the Act, and what obligations may apply.

The tool guides users through a series of questions to identify: the user’s role (provider, deployer, importer, distributor), the nature of the AI system (general-purpose, high-risk, limited risk), whether the system is used within the EU market, and then provides an indication of applicable legal obligations under the AI Act.

The interface is designed for embedding and broad use; it is described as a “simplified” instrument, offering early assessment rather than definitive legal advice.

Why it is relevant

For any organisation that develops, supplies or deploys AI systems, and for their legal advisers, the availability of a self-assessment tool is a helpful entry point to compliance preparation.

It reflects the regulatory intention to impose clear obligations by role and risk category rather than a one-size-fits-all model.

The availability of such a tool shows that compliance will be actively scrutinised, and that preparedness will likely become expected.

Courts or regulators may view use of such tools (or documented assessment) as evidence of a compliance-minded approach.

While the tool is useful, legal practitioners will need to caution users that self-assessment does not replace legal advice, documentation, or the full suite of compliance obligations under the AI Act.

The questions answered by the tool form a baseline; organisations will need to move from assessment into detailed documentation, governance updates, risk assessments, supplier/contractor reviews and perhaps certification (or future equivalent).

The tool also emphasises that each AI system must be assessed individually—if an organisation utilises multiple systems, each may have differing obligations.

Summary

The release of the compliance checker tool represents a practical aid to organisations utilising the AI Act.

Legal advisors should treat this as a platform of regulatory maturity: readiness is advantageous, and it becomes sensible to integrate structured assessments, role-based obligations and system-by-system reviews into compliance workflows.

4. The Joint Research Centre (JRC) Report: “A Framework to Categorise Modified General-Purpose AI Models as New Models Based on Behavioural Changes” (JRC143257)

The JRC has published a scientific study that addresses how modifications of general-purpose AI models (GPAI) may give rise to what should be recognised as new models for regulatory purposes under the AI Act.

The report presents two approaches for assessing when a modified GPAI has become a “new model” rather than a variant of the original:

Direct measurement of differences in capability profiles or instance-level answers;

Use of proxy metrics related to the modification process (for example fine-tuning, data-usage, computational resources).

The study underlines that distinguishing between an ‘updated’ version and a truly new model is critical because under the AI Act, different obligations may apply depending on how a model is categorised (for instance registration, transparency, higher oversight).

The report emphasises methodological challenges in measurement, the need for clear definitions, and the implication that model providers may need to document modifications and behavioural change metrics.

Implications for regulation and contracts

This report has several implications:

Vendor contracts and procurement instruments involving AI models should consider the possibility that a provider’s “update” may trigger new obligations under the AI Act if the modification results in behavioural change beyond a defined threshold.

Model governance frameworks need to include versioning, baseline behaviour metrics and documentation of modifications, along with change-logs that enable comparison of behaviour before and after fine-tuning or data updates.

Organisations using GPAI models must be aware that compliance obligations may not cease once version 1 is covered; subsequent modifications may constitute “new models” and thus restart regulatory timelines or obligations.

Legal risk assessment frameworks should incorporate the possibility that an AI provider may have to treat an updated model as a new product, with downstream liability or regulatory reporting implications.

The JRC report adds depth to the interpretive infrastructure of the AI Act by mapping how behavioural change and model modification intersect with regulatory categorisation.

Practitioners should build into their advisory frameworks the need for versioning, modification documentation and contract provisions dealing with “material change” in AI models.

Final Remarks

The four developments reviewed this week highlight a clear pattern: legal frameworks, standards and technology architectures are increasingly intersecting in tangible ways, rather than remaining abstract.

Organisations and their tech advisors are well-advised to make operational and contractual preparations now: governance frameworks need attention, system-by-system assessment is becoming essential, and documentation of AI model changes and their implications will be a necessary part of compliance.

Thank you for reading this week’s newsletter. I hope these insights help you stay informed.

I would love to hear your thoughts or experiences on any of these developments; feel free to share your comments or reply directly to this email.

But basically, could the involvement of AI in arbitration not undermine the perception of impartiality, especially so if parties believe the algorithm’s training data, prompts, or prior awards used for fine-tuning reflect bias or structural inequality in the dataset?

Great review for the week. Appreciate the effort.